Blur drummer DAVID ROWNTREE on the perils of touring Europe with his band before the era of open borders. And why Brexit would be such a damaging step backwards

Brexit is likely to be a disaster for touring musicians. I know this because I remember what it was like in the old days. I first started touring in the early 1980s, many years before Blur.

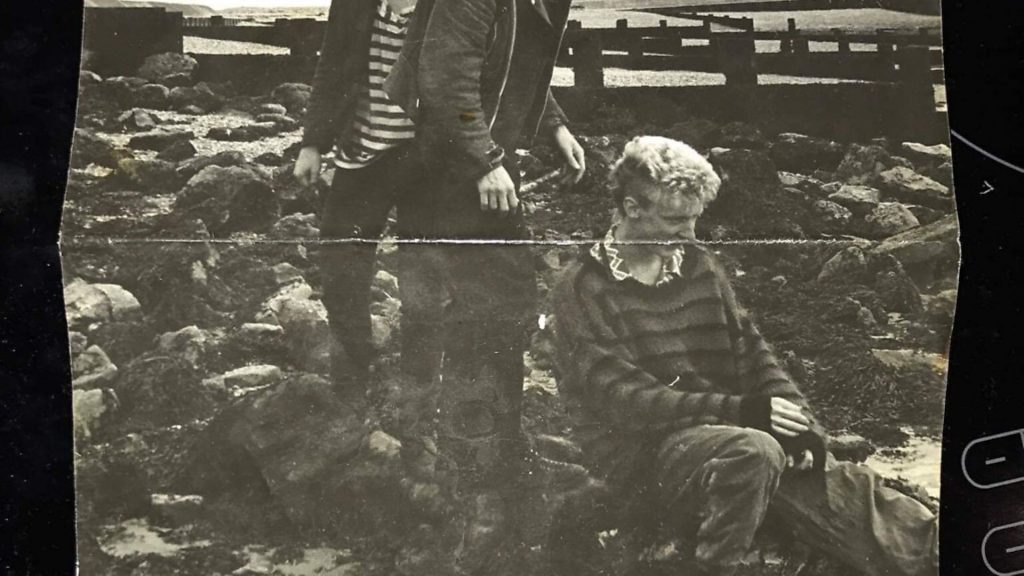

A group of friends and I were in a band in London. But like so many before us, we were struggling to make any headway with our careers. Eventually we had enough of playing the same London pubs and bars over and over to just a handful of people. Demoralised and exasperated, we decided to try something else.

One payday, we pooled our meagre resources and invested in an ancient Bedford CF van. We piled our worldly goods in the back and set off for France to try our luck on the continent.

The van was reliable, in that it reliably broke down every few hundred miles. Its Haynes Manual quickly became one of the best read of the small selection of books we’d taken with us, second only to the O-level French textbook we’d brought to try and make ourselves understood. Incidentally, my French has never progressed beyond the last page of that book. I’m still fluent only when explaining that the terrifying skeleton that Peter and Jane found in a cave on a beach was actually that of a cow.

The UK joined the EEC (which later became the EU), in 1973 but when we set off for France in the 1980s, trade between the UK and the Europe was far from frictionless. For a young touring band this turned out to be a nightmare.

When travelling, our lives revolved around a customs document called an EEC Carnet, on which we’d had to list every piece of equipment we owned, in laborious detail, complete with serial numbers.

When leaving a country, we had to completely unload the van and check every item against the Carnet with the customs officer, to make sure we hadn’t bought or sold anything while we were there. Then, a few yards away, when entering the next country, we had to repeat the whole process again.

The penalties for getting it wrong were onerous, including huge fines, and potentially the confiscation of all our equipment. Early on it was discovered that we had transposed two digits when writing down the serial number from one of my drums. Chaos immediately followed, which eventually led to us being frogmarched away and strip-searched.

Every border crossing had windowless rooms full of truck drivers, miserably clutching their flawed paperwork, staring grimly into the middle-distance, as if waiting for death to release them.

I remember being told to sit down and join them during the ‘transposition incident’. The full horror of the situation just beginning to dawn on me, I turned to the ashen-faced driver next to me, and whispered: ‘God! I had no idea it was going to be like this!’

Jolting him out of his malaise, he slowly turned to face me, eyes re-focussing from his thousand-yard stare, to see me, a young lad, clearly way out of his depth. In a low moan, he implored me: ‘Go home. Please for your sake, go home and don’t come back!’

Of course these days we could probably replace paper documents with electronic versions. No doubt there are all sorts of other technological advances that could help ease the pain. But the reality of Brexit, with or without a deal, will be a return to this kind of chaos and misery for touring musicians.

We know this because the government is already planning for it. Work has started to turn parts of the M20 and the M26 into lorry parks to house thousands of trucks. Panic hiring of customs staff is under way both in the UK and abroad.

Of course, musicians themselves will probably travel by train or air, but now they will need a visa – they had better hope they’re not flagged up on a database somewhere. And in the lorry park will sit their equipment. Some estimates say the tail-back will be as long as 60km, and the waiting time two to three days. I say dream on.

Maybe the guitars will arrive in time for the gig, maybe they won’t.

And the costs involved will be staggering. At a time when young UK musicians struggle to make ends meet, who can afford to pay their drivers to wait around for three days? They’ll need hotels and replacement crews; the trucks will need security; in winter they’ll need to keep their engines idling, so a thick layer of smog will descend on the south of England.

Maybe things will be smoothed out in the long term, but by then most of the smaller bands will have gone out of business. They rely on the potential EU audience of 500 million people; the UK simply doesn’t have the population or infrastructure to support them on its own.

This bleak scenario is why I’m calling for a final vote on Brexit, once we see the deal that’s being proposed. The government justifies the headlong rush towards Brexit by saying it’s ‘the will of the people’. Very well then, ‘the people’ must be in charge, and must be given the final say once we know what’s actually on offer. If the final deal really is better than staying in the EU then I’m sure everyone, including me, will vote for it.

I’ll be marching this Saturday to make my voice heard. I hope everyone who cares about the future of the UK’s creative industries will do the same.

David Rowntree is a Labour councillor on Norfolk County Council and the drummer for the rock band Blur