A thrilling tale which secured a story described as the ‘greatest scoop in the history of journalism’ – and the curious publication behind it.

The departure of the final few British service personnel from Germany in March marks the end of a remarkable and often forgotten story, which started when the guns of the Great War fell silent just over a century earlier.

It’s a story of a British colony in the heart of Germany, of cooperation, of conflict and tragedy. Lost within it is also an untold story about a newspaper which landed ‘the greatest scoop in the history of the world’.

It starts in 1918 when, one might guess from recent years’ coverage of the Armistice, British forces said ‘job done’ and went back home to Blighty until the next time.

In fact, some 270,000 of them remained and followed the retreating Germans, crossing the Hohenzollern bridge into Cologne as part of the Allied occupation of the German Rhineland.

The new adversary for Britain’s forces was boredom, behind which lurked the perils of Bolshevism and venereal disease. The occupiers had little to do, knew little of where they were, and not much more about the outside world because news from home took two days to reach them.

What they needed, according to a senior officer, was their own newspaper. Thus the Cologne Post was born, with four soldier-journalists starting work in a one-room office from 7am on Sunday March 30, 1919. It’s a date that ought to be more than a footnote in any timeline of European and journalism history, not least today, as Britain wrestles with the very idea of its place in Europe.

The Cologne Post staff struck a deal with Reuters for news to be sent over the military wires; started writing, editing, found a Koenig and Bauer printing press, and turned out a newspaper the next day. According to the Post’s own records, the soldier-journalists returned briefly to their billets for breakfast and baths before starting on edition number two, working some 43 hours with barely a break. (The launch editor, Captain William Rolston, was to die in his billet just over two years later, possibly of exhaustion, surrounded by cameras, typewriter and other journalistic kit).

The story of the occupation itself has been told, forgotten, and re-told but back copies of the newspaper itself lay largely undisturbed in the archives of the British Library reading rooms. The dust falls from between pages unturned for a century. The service records of the soldiers and officers who ran the paper are to be found in the National Archives at Kew, similarly untouched.

All of which is remarkable given that within two months of its launch the Cologne Post broke what was billed as the biggest story the world had ever known. As scoops go, it is still up there with one of the greatest, and strangest.

The story of the scoop features not a journal with a history of investigations, but a less likely newspaper which looked, to some extent, like an official organ of the army. The Post, however, was nothing of the sort, occupying instead a unique position in the no-man’s land between the state and the market.

The army provided some start-up cash, but only as a loan to be re-paid through advertising. Now and then, questions would be asked, including in parliament, about this journalistic oddity and the answers were as opaque as the true status of the journalists themselves.

That status was tested to the extreme when, on May 7, 1919, the German delegation entered the Hall of Mirrors at the Trianon Palace at Versailles to receive, finally, their copy of the 200-page draft treaty which would shake Europe to its core for decades to come. The armistice of November 11, 1918, had ended the fighting, but this treaty would establish the real nature of the peace.

Yet, incredibly, only hours after the German officials at Versailles were handed the draft of the treaty, a newspaper of which few people have ever heard was the first in the world to publish a detailed account of what it contained.

Indeed, so fast was the Post with its historic scoop that its readers – including German citizens in Cologne – saw the treaty even before it reached the German government in Berlin.

Often in its 10-year history, the Post looked back on that event, calling it ‘the greatest scoop journalism has ever known’ and ‘the biggest scoop in the history of newspaper effort’.

This is how they did it… The Post appeared to have someone on the inside at Versailles, and managed to get a copy of the treaty flown from Paris, then on to the newspaper’s offices in Cologne via a courier with an armed motorcycle escort.

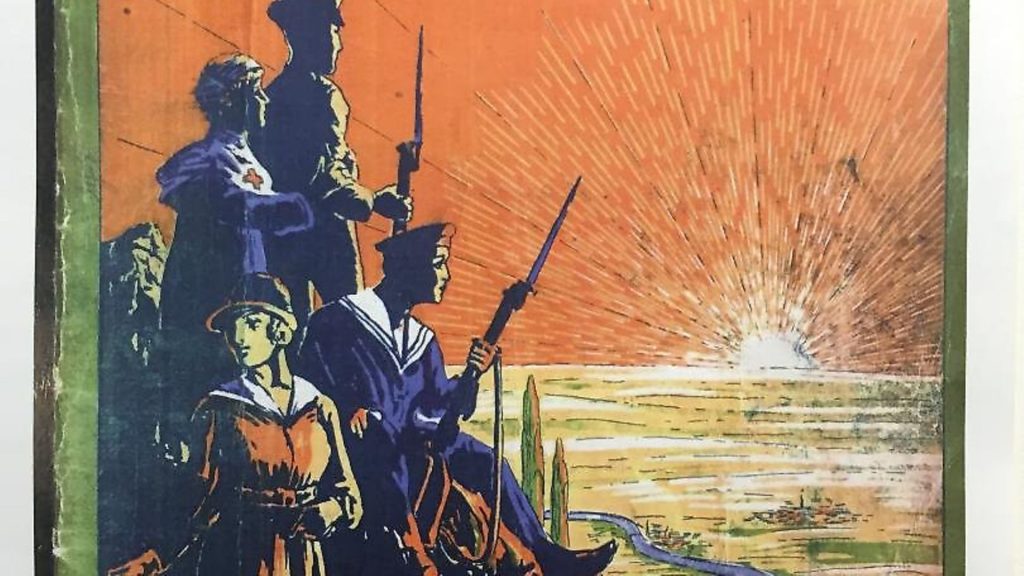

British soldiers with fixed bayonets stood guard at every entrance to the newsroom and press. Up to this point, it could have been an officially sanctioned military media exercise.

The guards barred all entry or exit until the machines began printing, with one exception. They allowed in a messenger with a mysterious telegram. The message was delivered to acting editor Sergeant Major Nevill who, much later, would become the Reuters correspondent in West Germany. Nevill opened the message, read it, put it in his pocket, and said no more.

Only when the Post’s spectacular edition had hit the streets did he show the telegram to his editorial colleagues. It was an army order to halt publication of the draft treaty. He was a soldier, and had defied an order; but he was also a journalist, and had the scoop of his life.

How the Post got hold of a copy of the treaty before its general release, and how Nevill was brave or mad enough to ignore the order, was subject to what may have been later journalistic myth-making by the cast of this drama.

At first the paper, which published periodic stories about its own history, was coy about it. In 1920, it reflected only that: ‘Just how it was accomplished is an interesting story that may not yet be revealed.’

By June 1928, with enough distance from the event, it began hinting at the truth: ‘Everything had been carefully planned for that dramatic coup and the plans were within an ace of fruition when a wire came. What that wire contained, who opened it, and who so far forgot to mention its ‘verboten’ contents until the edition was on sale, can be guessed.’

Elsewhere, it teased readers by describing whoever saw the telegram as having a ‘lapsus mentis’ (a slip of the mind), which ‘bypassed the interdiction and secured the scoop’.

The story hardened somewhat, into full heroic mode, with Nevill himself being quoted eventually as having said: ‘I don’t care if they hang me for it… we’ve got the greatest scoop ever known.’

On the day of the scoop itself, the Post acted like any other newspaper – plastering Cologne with posters advertising an imminent special edition. Outlying army units were alerted by telephone. Within four hours, the story was set and printed. By mid-evening, according to the Post’s own retrospective accounts, the courtyard outside the printing works was ‘a mass of excited humanity’.

The special edition came off the press. It carried what was, for those days, a huge headline across all five columns: ‘The draft Treaty of Peace ‘For the prevention of wars in the future and for the betterment of mankind’.’ The summary of the draft terms were laid out under 15 separate headings.

Those gathering outside the Post’s premises in Cologne would be the first in the world, apart from those directly involved in Versailles, to know what Germany was being forced to accept.

The Germans of Cologne, the Post would recall in 1920, ‘waited with undisguised anxiety to know the price demanded – take it or leave it – for having sought arbitrament by the sword. They read their Fate in the Cologne Post, which acting as the mouthpiece of the Allies, was something much greater than a mere newspaper which had brought off a world’s record’.

The terms were shockingly onerous, and even the process itself humiliating. The German delegation at Versailles had travelled to France on April 28, 1919, and been kept waiting for more than a week while the Allies completed their 75,000 word draft treaty. On May 7, the Germans were given just one copy and worked through the night to create translations for dispatch to their government in Berlin.

But the Post had already run it, and by that evening its staff had already retired to celebrate their scoop at a bar in the city frequented by local journalists. As they entered, they later reported, ‘the high note of excited conversation ceased abruptly and dead silence ensued’.

‘The only sound in the salon was of our glasses being filled. We stood and said ‘Prosit’ to them and ‘cheerio’ to each other. Then one came across, offered his hand and said in a broken voice: ‘Our colonies and our ships.’ We left at once, being bowed out with punctilious politeness.’

Germany was to lose not only all its colonies and merchant navy, but also one third of its coalfields, three-quarters of its iron ore deposits and one third of its blast furnaces. Its army and navy were to be reduced to ‘pitiful proportions’ and the level of reparations was still to be set. John Maynard Keynes, who was part of the British delegation, described the terms as an unbearably harsh ‘Carthaginian Peace’. The impact of the punitive treaty would be exploited by Hitler’s National Socialists bent on revenge against all those – socialists, Jews, and the allies – who they blamed for the ‘stab in the back’.

With its scoop achieved, the Cologne Post went back to business as usual, taking its place in history not just as a lens through which the occupation can be viewed, but as a journalistic curiosity in itself.

It continued to face questions about its status, calling itself a ‘semi-official’ organ with some public funds being invested in what acted like a private venture. Its hybrid status was, in some respects, similar to that of the BBC – founded in this period at an arm’s length from the state, but insulated from the pressures of the market.

The Post achieved an odd kind of public service journalism, acting as a community-builder for the garrison and a mouthpiece for the occupiers. It reported on and sponsored a lot of sport, offering what it called a ‘healthy English mental environment for spending the most impressionable years of adolescence among the subtle temptations of an unwholesome German town’.

It acted as a kind of Google for the occupiers, offering to settle any mess disputes, with letters to the editor asking, for example, when the Lusitania was torpedoed, or when Crippen had been hanged. As the garrison settled into a smaller and family-based posting, it ran features for wives, and a children’s club.

The Cologne Post defended its readers with a passion, hitting back, for example, at a Daily Express article which alleged that British soldiers were routinely playing soccer with Germans. The Post called the Express article ‘a gross libel on the British Army of the Rhine’.

By the time of the Post’s demise, when the last of the garrison departed in November 1929, the newspaper was painting a picture of itself as having bravely triumphed against adversaries from within as well as outside the British establishment.

A.G. Clarke, its leader writer, said the paper had fought continually for its semi-independent status and avoided, ‘time after time’, being nearly ‘killed by distant officials who knew little of its influence’.

The Cologne Post closed down, but the British would be back – just 16 years later – for another, longer, occupation, as part of a new European order after the defeat of a Germany that had driven itself towards armageddon in response at least in part to the humiliation of the peace treaty of 1919. A treaty published first by a few audacious journalists on a unique newspaper which scooped the world.

• Dr Robert Campbell has a background in newspaper journalism and is head of journalism at the University of South Wales; with James Stewart, he has written The Newspaper that Scooped the World: The Cologne Post and British journalism in the occupied Rhineland 1919-1929 (Kindle Edition. £9.99)