The Russian city has not only produced brilliant music, but – amid horrors of war – one of history’s greatest performances.

Saint Petersburg is a city of beauty and brutality. Peter the Great founded his grand capital in 1703 as a Baltic port city that “hack[ed] a window through to Europe”. But while it took the canals and townhouses of Amsterdam and Venice as its inspiration, its baroque beauty was built on the backs of tens of thousands of forced labourers.

By the end of the 18th century and the reign of Catherine the Great, Saint Petersburg was a byword for opulence but around half the Russian population had been swallowed up by serfdom by that time.

This city built on boggy marshland suffered repeated floods, the biggest in 1824, and Dostoevsky – a Muscovite who found literary success, political intrigue and a home in Saint Petersburg – would write of an insalubrious cesspit of a city, claiming in Crime and Punishment: “There are few more grim, harsh and strange influences on a man’s soul than in Petersburg.”

While Saint Petersburg maintained its historic grandeur in the 20th century, it also became subject to the whims of successive Soviet regimes and ultimately the scene of unspeakable brutality.

Renamed ‘Petrograd’ in 1914 to remove its Germanic implications, four years later the city lost its capital status after 200 years when Lenin moved the designation to Moscow. After his death in 1924 it would be renamed ‘Leningrad’ in tribute to him.

This home of aristocrats and intellectuals was turned upside-down by the Red Terror and the Stalinist purges, and in the early 1940s hundreds of thousands of civilians died during the 900-day German siege of the city, when three sparkling white winters were the backdrop to unimaginable hardship.

After the war there was instant rebuilding – brutalist tower blocks sprung up around the centre, the bombed Hermitage was repaired, and lavish, marble-lined metro stations were built beneath the city streets.

In the 1990s gang violence saw blood spilled on the streets, while native Leningradtsy Vladimir Putin used a position in the mayor’s office to begin building his tainted power base. But the undeniable magnificence of Saint Petersburg has survived it all and it has proven to be a city where music has meant power, the expression of national character and defiance of oppression and violence.

While Peter the Great had seen European music as a mark of Western-style modernity and, therefore, a political tool, his daughter the Empress Elizabeth was a genuine enthusiast, spending lavishly on French musicians and Italian opera singers for her court.

When Catherine the Great came to the imperial throne in 1762 she combined both impulses. Although not a musician, she wrote nine libretti for opera, including the allegorical fairytale The Story of Tsarevich Fevey. With music by composer of comic opera Vasily Pashkevich, the work premiered in 1786 at the grand theatre she had built inside the Winter Palace.

Pashkevich later became the first violin of the court orchestra and was given charge of imperial ballroom music, while the Ukrainian Cossack violinist Ivan Khandoshkin also enjoyed Catherine’s favour, becoming kapellmeister early in her reign. But Khandoshkin’s music, including his five violin concertos, was just a small part of the programme of local and international music at Catherine’s court, which included many compositions by the court’s women, from singer and composer of folksongs, Mariya Voinovna Zubova, daughter of a vice admiral, to Princess Varvara Nikolaevna, who married into the Dolgorouky dynasty.

The compact and relatively primitive square piano Catherine commissioned from the London-based German maker Johann Zumpe remains on display at Saint Petersburg’s Pavlovsk Palace to this day.

In the 18th century, Saint Petersburg got a new musical impetus from a foreign source as well as its very own musical legend. The cultural superstar Liszt made his debut in Saint Petersburg during his first visit to Russia – a four-week trip beginning in the April after ‘Lisztomania’ had first broken out in Berlin in late 1841. Debuting at the Assembly Hall of the Nobles to an audience of 3,000, he was a sensation, with critic Vladimir Stasov writing “Never in our lives had we heard anything like that; we had never been in the presence of such a brilliant, passionate, demonic personality.”

Later in the tour, Liszt played a piano made by Hermann Lichtenthal in his Saint Petersburg workshop, and he also gave his endorsement to Mikhail Glinka – a pioneer of a distinctly Russian classical music – by arranging a march from his Ruslan and Lyudmila for piano.

Often cited as the first thoroughly Russian opera, this work, based on a Pushkin poem and strongly marked by native folk music, premiered in the city the November after Liszt’s visit.

The pursuit of ‘Russianness’ continued into the latter half of the century, as Mily Balakirev, 30 years younger than Glinka, developed work in a similarly nationalistic vein, while also being strongly influenced by Liszt. Forming part of ‘The Big Five’ with Rimsky Korsakov, Cesar Cui, Modest Mussorgsky and Alexander Borodin, he founded his Free School of Music in the city in 1862 as a direct rival to Anton Rubinstein’s Saint Petersburg Conservatoire.

Balakirev’s later friend, Tchaikovsky, would graduate from the Conservatoire in 1865 and in the coming years his work finally put Russian-made classical music on the international radar.

The birth of Stravinsky in the city in 1882, the graduation from the city’s Conservatoire of both Rachmaninoff, in 1892, and Prokofiev, in 1914, as well as Tchaikovsky’s death in 1893 – allegedly after suicidally drinking a glass of cholera-infected water at Leiner’s restaurant on the city’s main street of Nevsky Prospekt – marked the end of the long 19th century and beginning of the 20th. It would be one of untold struggle in Saint Petersburg, but music would still ring out.

A 32-year-old Dmitri Shostakovich faced the outbreak of war having ducked the Stalinist purges that had engulfed so many of his family and friends, despite his music being condemned in Pravda, the mouthpiece of a regime that simultaneously suppressed free expression while expounding on the rights of the ordinary worker to the very best of culture.

He was in Leningrad as the siege of the city began two years later and, while also serving as a volunteer firefighter, he wrote the first three movements of his dramatic, turbulent Seventh Symphony in a city that was falling into chaos.

Evacuated 1,000 miles east to Kuibyshev in October 1941, Shostakovich finished his symphony – one which was punctuated by war-like drums and characterised by both a sense of struggle and of hopefulness – and premiered it there in March 1942.

By that time, the sufferings of the winter of 1941-42 had reduced Leningrad to a starving, battered city, but that summer the work would nevertheless be performed in Leningrad itself in one of the most moving and dramatic musical performances in history.

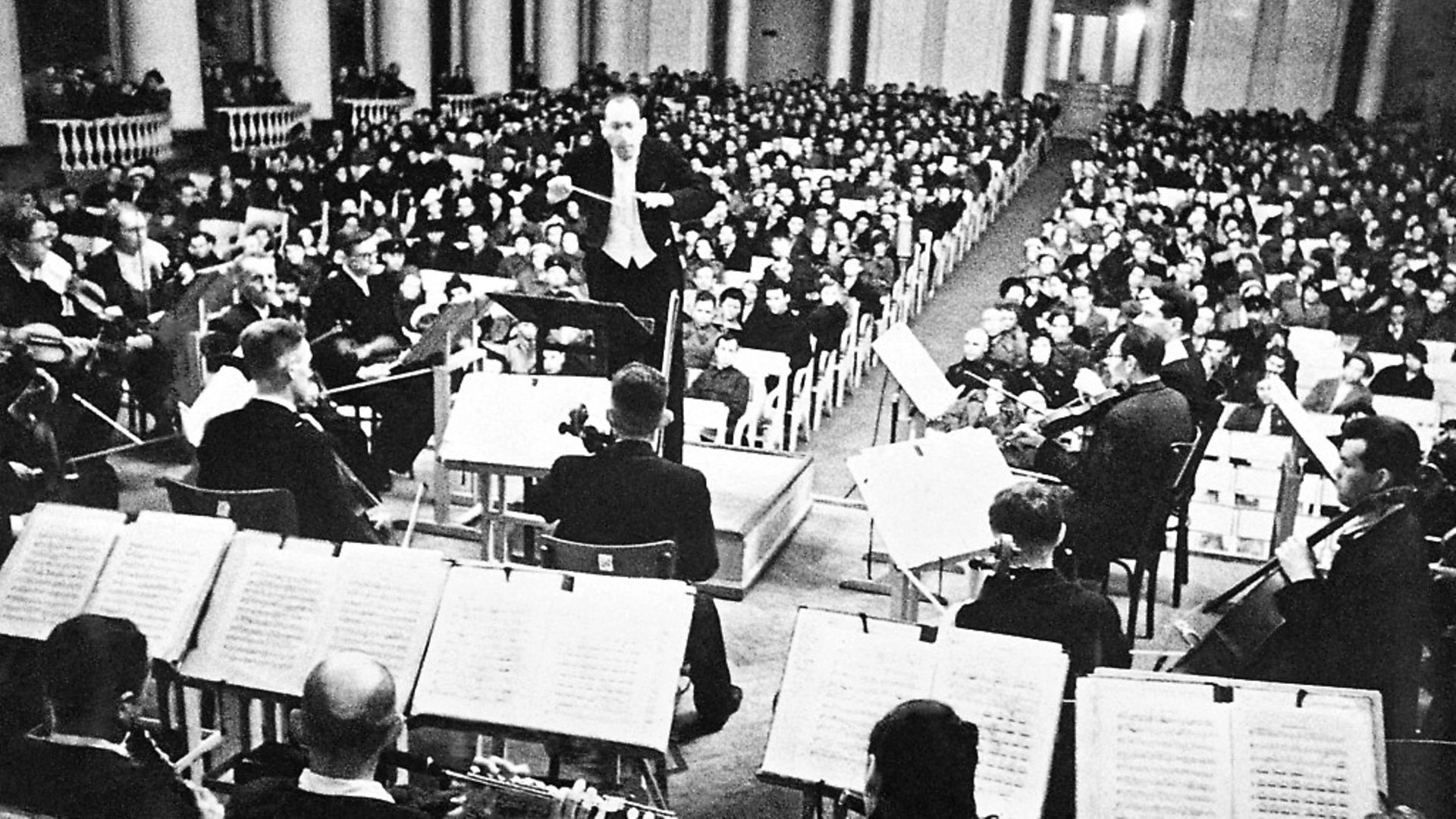

The Leningrad Radio Orchestra had been on a six-month hiatus when conductor Karl Eliasberg tried to reassemble it in mid-1942 with the purpose of giving Shostakovich’s Seventh its Saint Petersburg premiere.

Many of the players had not survived the winter, those that remained were starving, and any available musician, including serving soldiers, was drafted in to make up the numbers.

Rehearsals often broke up early for sheer lack of energy, but on the evening of August 9, 1942, Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony was performed at the chandelier-festooned Philharmonic Hall by the black tie-clad players. Blasted out by loudspeakers all around the city so the German lines could hear it, a greater act of defiance would be hard to conceive of.

Shostakovich dedicated his symphony to the people of Leningrad who went on to suffer another year and half of siege, and his Eighth Symphony of 1943 would reflect the sombre mood of those years, despite the Red Army having by that time gained the upper hand over the Germans. Its less than triumphant tone earned him another ban by the authorities.

This survival of music against the odds in Saint Petersburg was no better represented than by the ‘jazz on bones’ phenomenon. While the avant-garde had briefly thrived in the 1920s – Leningradtsy Léon Theremin’s invention of one of the earliest electronic instruments was a potent symbol of this – under Stalin the authorities cracked down on the innovative, the ‘bourgeois’ and the Western in favour of patriotic music. But one Saint Petersburg native, Stanislav Philo, sidestepped the bans by establishing a black-market trade in recordings crudely copied on to used X-ray film on which the medical images were still visible – hence the name.

Tchaikovsky once said: “Truly there would be reason to go mad were it not for music.” But in Saint Petersburg, it seems, the preservation of music in the face of adversity has led to madness in the form of daring defiance.