How Italians are using their shared musical heritage to get through a national crisis.

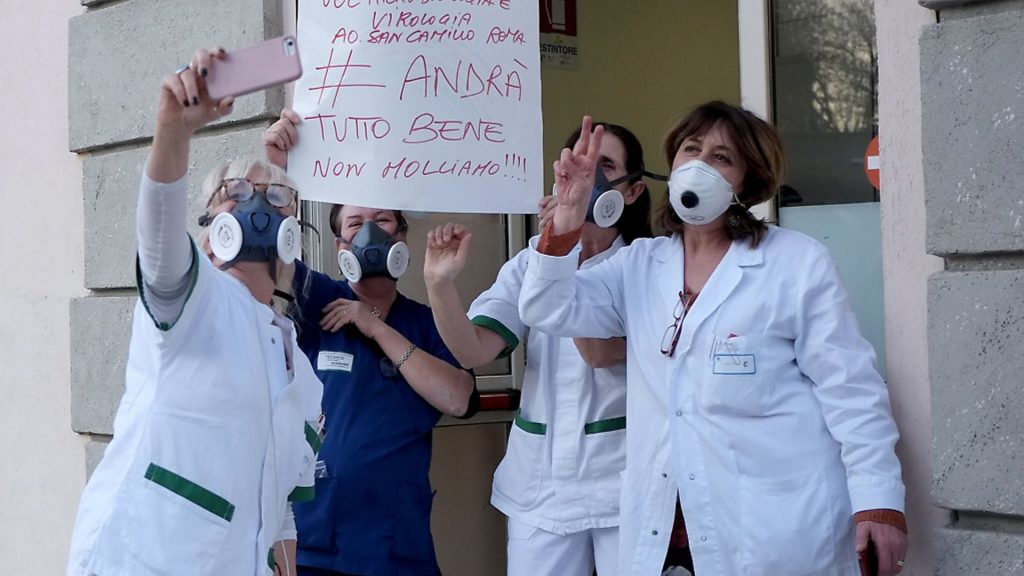

Across Italy, music has been connecting people as 60 million have been confined to their homes. At the end of the first week of the national lockdown, an initiative was launched in Rome which touched the whole country. Brass collective Fanfaroma’s Flash Mob Sonoro urged people to ‘open the windows, step out onto the balcony and play together’. Some sang, some played, others simply banged pots and pans. Another flash mob event branded Mestolata Collettiva (‘Ladle Collective’) on the following day fully embraced that most primitive method of music-making.

The songs Italians chose to sing were wide and varied. Many opted for the national anthem, Il Canto degli Italiani, its opening line speaking of ‘brothers of Italy’ making it a rallying cry for unity. But across the country everything from the Macarena to Imagine and the Ode to Joy has rung out across rooftops. In the capital itself, Romans have turned to pop classics and celebrating their city in music, while a song that got its latter-day fame in Rome was performed has come to stand for Italy’s defiant hope in the face of unimaginable crisis.

Italy’s turn-of-the-century composers were certainly caught up in the romance of Rome, a city with a history and architecture unlike any other. Professor of composition at Rome’s Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia for almost a quarter of a century, Respighi, used Roman landmarks, from the Villa Borghese and Piazza Navona to the Trevi and Triton fountains throughout his trilogy Pines of Rome, Fountains of Rome and Roman Festivals.

Meanwhile, Puccini was commissioned to write the Inno a Roma (‘Hymn to Rome’) to honour the Italian victory in the First World War, but its triumphal tone saw it soon widely adopted by the Fascists.

More enduring is Puccini’s Rome-set Tosca, where the Sant’ Andrea della Valle basilica, the Palazzo Farnese, and the Castel Sant’ Angelo form the backdrop to its three acts, and it premiered in the city in 1900.

Maria Callas made the title role her own, the 1953 recording of her appearance at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala being one of the most famous in the history of opera. Her performance of the aria Vissi d’arte – capturing Tosca’s bewildered reaction to her undeserved fate (‘Why, why, o Lord/ Why do you reward me thus?’) – is heart wrenching in the context of Italy’s suffering.

Yet, in extremis, bel canto has been passed over for pop on Italian balconies. Grazie Roma, the 1983 single by multi-million selling singer, songwriter and pianist Antonello Venditti, was captured booming out over the southern Roman district of Mostacciano two weeks ago, its wordless intro lending itself perfectly to a community singalong. Venditti was born in Rome and is thoroughly invested in the city’s mystique, often writing songs in the local Romanesco dialect. Grazie Roma itself was inspired by A. S. Roma winning the Italian Football Championships after a 41-year drought in 1982, football being taken only slightly less seriously in Rome than religion.

The accompanying music video opened with sweeping shots of Rome before focussing on Venditti sitting at a white grand piano in the middle of the Colosseum.

Venditti originally made his name with another ode to the city of his birth, the heartfelt folky ballad Roma capoccia (‘Rome the Boss’) (1972), a song he had first debuted at Trastevere’s basement Folkstudio club, a place he namechecked on his 1973 song Dove (it was a place with a legendary reputation – Bob Dylan played there in the early 1960s). The song was an unabashed love letter to the city: ‘How beautiful you are Rome when it is evening/ How vast you are Rome when it is sunset/ I stopped here and I see the majesty of the Colosseum/ I see the holiness of the dome/ I was born in Rome.’

Singer and broadcaster Luca Barbarossa’s debut single Roma spogliata (‘Rome Stripped’) (1981), on which Venditti played piano, saw the native Roman Barbarossa pay affectionate tribute to a seedier Rome of wet streets populated by cats and ‘puttane’.

Barbarossa’s more recent Roma è de tutti (‘Rome Belongs to Everyone’) (2018), meanwhile, celebrated the city’s diversity, home both to those ‘who are born and who arrive here’, ‘those who go to church, and those who forget all the saints’.

But it is easy to see why it was Venditti’s Grazie Roma that spoke to the times for quarantined Romans, the song beginning: ‘Tell me what it is that makes us feel friends/ Even if we don’t know each other/ Tell me what it is that makes us feel united/ Even if we are far away.’

Meanwhile, residents of one set of Roman apartment blocks sang Nel blu, dipinto di blu (‘In the Blue Painted Blue’) in unison, even if not quite in tune. Known in the Anglophone world as Volare, the 1958 cover by Dean Martin made it famous, and Martin’s career-long capitalisation on his Italian roots in fact included a few homages to Rome, with 1962 album Dino: Italian Love Songs containing the string-soaked Arriverderci Roma and the more jaunty On An Evening In Roma (Sott’er Celo De Roma). But the song was written and originally sung by Domenico Modugno, the most successful Italian recording artist in history and the father of modern Italian song.

Modugno was already a successful actor and songwriter when he was inspired by the blue tones of a Chagall painting to write Nel blu, dipinto di blu. He took it to the San Remo Music Festival in 1958 and won, the first of four such wins over his career, and the song was chosen to represent Italy at the Eurovision Song Contest that year.

After a glittering career in music and film, Modugno entered politics, putting his passion for human rights and social justice into practice, and he was elected as a member of the Chamber of Deputies for the Radical Party in 1987, ultimately becoming a member of the Italian Senate for a Roman constituency in 1990. Modugno died in 1994, but his Nel blu, dipinto di blu remains as his gift to Italy, its joyous and anthemic chorus – ‘Volare, oh, oh/ Cantare, oh, oh, oh, oh’ (‘I fly/ I sing’) sung in the midst of the shutdown of a nation an almost unbearable fantasy of freedom.

But the balcony performance that has captured imaginations around the world is tenor Maurizio Marchini singing Nessun Dorma from Puccini’s Turandot from his Florence balcony.

This is another song inextricably linked to both football and Rome. The BBC famously used a recording of Pavarotti’s performance of the song with the London Philharmonic Orchestra at Kingsway Hall in 1972 for their coverage of the 1990 World Cup, sending it to No.2 in the charts for three consecutive weeks in June that year (Elton John’s Sacrifice kept it off the top).

On July 7, the night before the Italia ’90 World Cup final between West Germany and Argentina, the Three Tenors performed at the ancient Baths of Caracalla in Rome, and the recording was later released as Carreras Domingo Pavarotti in Concert. It is one of the bestselling classical albums of all time.

While Pavarotti sang Nessun Dorma solo earlier in the Italia ’90 concert, at the finale it was sung in turn between the three, and they united on the triumphant final bars apparently spontaneously, causing conductor Zubin Mehta to literally leap for joy. But in Marchini’s performance, the final word of the piece set against its soaring ending became a poignant statement not of triumphalism, but of hope: ‘Vincerò’ (‘I will win’).