The French town may not have produced much of its own musical heritage, yet it boasts one of the greatest venues in the world. SOPHIA DEBOICK reports.

The atmosphere of a venue can make the difference between a so-so musical experience and one that speaks to the soul. There are no more affecting venues than the surviving amphitheatres and arenas of the ancient world, and the 1st century AD théâtre antique of the Provençal town of Orange, 15 miles north of Avignon, is one that has built a particular reputation. Seating 10,000 people and with a monolithic 100-metre long façade (Louis XIV called it “the finest wall in my kingdom”), the theatre has a niche-filled scaenae frons which has provided the most dramatic of backdrops to modern performances. Since it was revived at the beginning of the 19th century after centuries of disuse, it has hosted everyone from opera legends to anarchic rockers.

Orange was known to the Romans as Arausio and was built as a perfectly planned town where all roads led to a grand monument or civic building that testified to Rome’s mighty power. The town’s triumphal arch features reliefs depicting the visceral violence of the Roman campaigns in Germania and Gaul, and stood as a constant reminder of the subjugation of the locals by Julius Caesar in the middle of the 1st century BC.

Since entertainment was never just entertainment in Rome, the theatre had political significance too. Built under the Emperor Augustus, it was a sign of his consolidation of the empire’s hegemony, even as Rome’s dominion was extended, the theatre’s awesome proportions and spectacular entertainments serving the crucial political purpose of keeping this colonial population happy and, therefore, quiet.

With Orange’s social groups carefully segregated in the stands, mimes, pantomimes and comic farces would be performed.

Mimes were a light kind of entertainment, involving dialogue, dancing, and singing that was accompanied on the tibia, the reeded, double pipe instrument derived from the Greek aulos, and the scabellum, a pair of cymbals on a wooden clapper that the tibia player would operate with their foot.

The masked pantomimes took on more serious themes and were far more elaborate musically, with accompaniment from a choir and orchestra that included a range of percussion instruments, the stringed zither and lyre, as well as panpipes (syrinx) and tibiae.

Orange’s theatre fell silent when it was closed down as Christianity took hold. The Visigoths pillaged it as the empire fell, and later it served as a refuge for the Protestant townsfolk during the Wars of Religion and as a prison into the 19th century.

Restored under the vast programme of works instituted by the inspector general of historical monuments, Prosper Mérimée, the theatre was reborn with a concert in August 1869, which included a performance of Étienne Méhul’s Biblical opéra comique, Joseph, and which marked the start of what became known as the Chorégies d’Orange – a musical event that continues to this day.

From 1902, the Chorégies would become an annual summer festival that harked back to the diverse entertainments of the Roman age, with dramatic works performed alongside opera and orchestral music. It drew the cream of the talent from Paris’ Comédie-Française, the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique, and Sarah Bernhardt played the eponymous role in Racine’s Phèdre there in 1903.

Since 1969, the Chorégies has become almost solely concerned with opera, and last year’s 150th anniversary was marked with Uruguayan baritone Erwin Schrott in Mozart’s Don Giovanni and French soprano Annick Massis in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell, as well as performances by Placido Domingo.

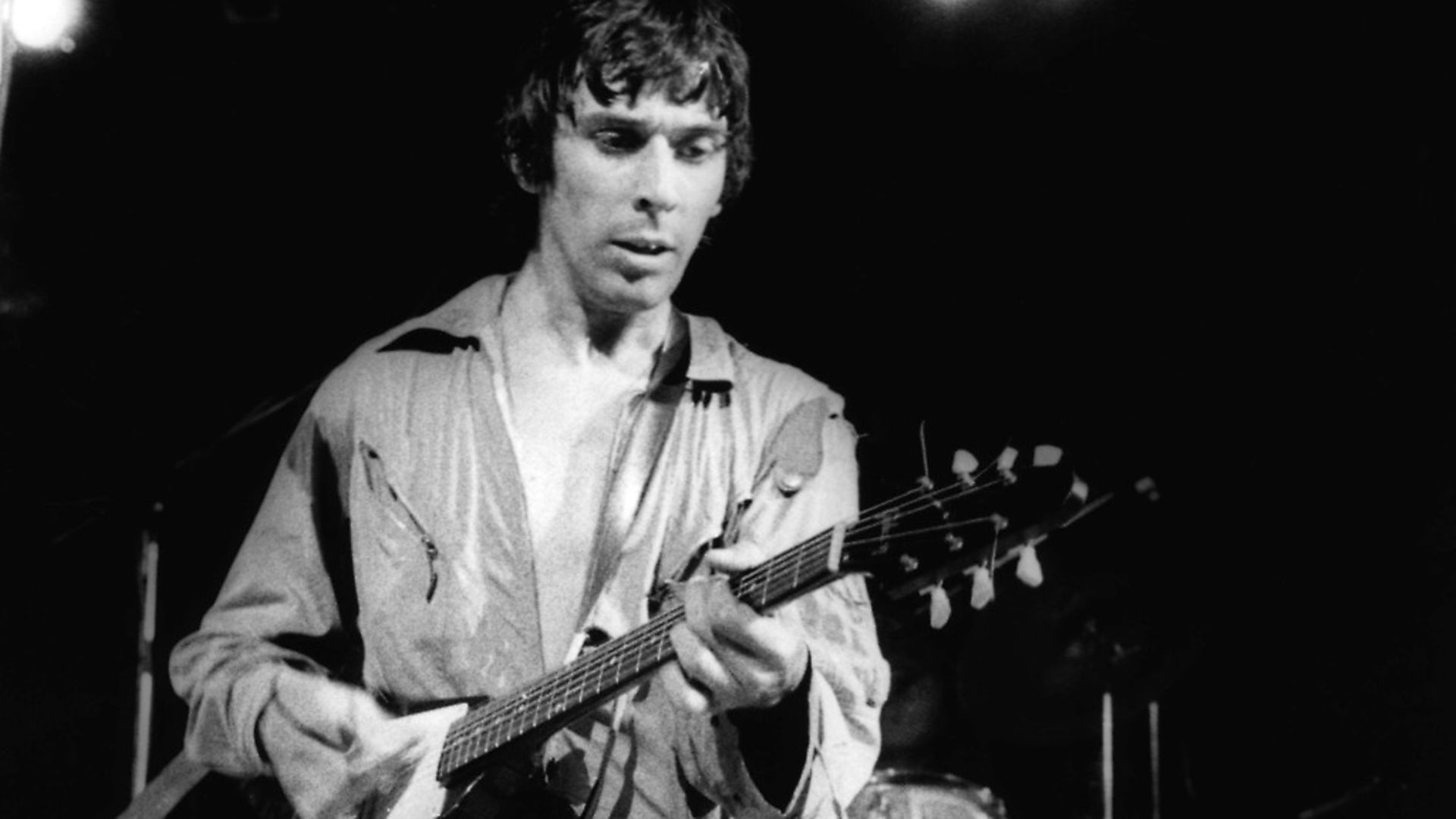

But it is not only the strains of the greatest stars of opera that have reverberated around the théâtre antique in recent decades. Rock came to the south of France in a big way with Orange 75, a three-day festival in mid-August 1975. Billed as ‘the French Woodstock’ – a tagline with associations that made the locals, more used to the genteel clientele drawn to the Chorégies, take fright – the festival was headlined by Bad Company, Procol Harum and Wishbone Ash, and also featured John Cale and Nico, Fairport Convention, Tangerine Dream, Ginger Baker, John Martyn, Mahavishnu Orchestra and Soft Machine.

Eric Burdon of the Animals and Lou Reed were prominently billed but failed to appear. But the stand-out act was Essex pub rockers Dr Feelgood, Melody Maker confirming they “received the biggest ovation of any act through the three days”, their appearance on day two “providing an object lesson to bands who flounder in complexity for complexity’s sake” with “songs punched out with fire and drive”.

Dr Feelgood had released their debut album, Down by the Jetty, early in the year, and their set mixed songs from the album with covers from the golden age of rock ‘n’ roll – Leiber and Stoller’s I’m a Hog for You and Riot in Cell Block Number Nine – finishing up with Route 66.

The psychotic double act of frontman Lee Brilleaux, in trademark filthy white suit, and Wilko Johnson, in trimly-cut black, matched the tense atmosphere – the venue was dangerously full beyond capacity and the Paris chapter of the Hell’s Angels was providing ‘security’.

The NME noted “the odd atmosphere of edginess-mixed-with-ecstasy”, and this was captured in footage of the night, subsequently used in Julien Temple’s Oil City Confidential (2009). Other than the film of the Feelgoods’ performance on home turf at Southend’s Kursaal later the same year, it stands as the best evidence of a band whose live ferocity was never fully captured on record.

Another career-defining concert film made at Orange would come in the following decade. Filmed on three consecutive nights in early August 1986, The Cure in Orange was directed by the band’s key collaborator, Tim Pope, and captured them at a pivotal stage in their history.

With a line-up widely considered classic, the band’s recent The Head on the Door LP, featuring the singles In Between Days and Close to Me, had seen Robert Smith’s writing shift from post-punk gloom to off-beat but soaring pop. The band gave several career-best performances of their material to date, as Pope alternated between sweeping shots of the dramatically-lit scaenae frons – including the band climbing to the central niche to take their curtain call by the 11 foot statue of Augustus – with shaky, hand-held extreme close-ups of the band.

The band opened with the stuttering menace of Shake Dog Shake, causing the crowd standing in the orchestra – where the highest status Romans once sat – to instantly form an incongruous but vicious-looking mosh pit, but the atmospheric A Night Like This was perhaps the highlight of the night, the black-clad Englishmen revealing that their warped love songs were, bizarrely, perfect for a warm Provençal night. But even their earlier material, like the ominous One Hundred Years (its opening line is “It doesn’t matter if we all die”) and the gothic tale of A Forest suddenly seemed tailor-made for a venue with such gravitas. Despite becoming known as a peerless live act since, their epic 40th anniversary shows of 2018 made into another Tim Pope concert film, The Cure have rarely been better than they were on those nights in Orange.

The théâtre antique is still providing entertainment into the second decade of the 21st century. This summer, as well as the Chorégies, it will host a musical retelling of The Lord of Rings and The Hobbit, Simple Minds and an evening of the music of Hans Zimmer. But no matter who performs there, the weight of history hangs heavy in a place where music is enjoyed just as it was 2,000 years ago, and the distance of time evaporates.