The broadcaster’s problem is a bad case of liberal guilt, argues Chris Grey.

I’m a great admirer and supporter of the BBC, and think it one of Britain’s greatest institutions. I also think its coverage has been skewed in favour of Brexit. That isn’t the same as saying that it has been flagrantly biased: it is more subtle than that. I don’t think the BBC is under the thumb of the government, or of the Leave campaign, or of UKIP. And I certainly don’t mean to imply that the BBC doesn’t think carefully and seriously about accuracy, balance and impartiality.

Even so, I think that, as regards Brexit, the corporation has, in some crucial respects, got its approach to these issues wrong. I don’t pretend to have undertaken a systematic study of their coverage – like most people I dip in and out of it. I also dip in and out of other broadcasters, mostly Channel 4 News, Sky News and ITV News. I’m aware of the possibility that my estimation of the BBC’s approach is no more than a reflection of my own views and biases about (and against) Brexit. Yet if I only saw through that prism then presumably I would be one of those who sees the coverage of those other broadcasters as pro-Brexit, which I’m not.

I’m equally well aware that there are very many people who regard the BBC as being biased against Brexit. That isn’t, though, to accept the argument that since both sides of the debate accuse the BBC of bias this suggests that the position is about right. Precisely because of the polarisation of views over Brexit, the BBC would attract criticism from both sides almost whatever it did, so that criticism cannot in itself be taken to prove their approach is the right one since it would occur even if they had a different one.

My overall sense is that the BBC has erred towards a subtly pro-Brexit stance. A recent example was the heavily criticised lack of coverage of large anti-Brexit marches in various cities. Other broadcasters gave the marches more prominence, and did so earlier, and exactly the same criticism was made of the lack of BBC coverage of an anti-Brexit march in March 2017. It is impossible to be sure, but I think that comparably-sized pro-Brexit marches would have been more prominently reported.

To take a converse case, last August the BBC gave prominent coverage to the Economists for Free Trade (formerly, Economists for Brexit) report claiming huge benefits from a hard Brexit. Why? It was not new. It was based on work reported before the referendum, albeit re-published in new form. And the underlying work had been heavily criticised by several leading economists. That is not, as Nick Robinson suggested at the time, a ‘censorship’ argument – every day all kinds of research are put into the public domain but it’s not censorship that very few are selected by the BBC. I am not certain, but my memory is that no other broadcaster gave any prominence to this story.

This feeds into a wider issue of the prominent platform given by the BBC to certain pro-Brexit figures. The most egregious example is the joint-highest tally of 32 appearances on Question Time by Nigel Farage, which continued even after he ceased to be UKIP’s leader. It could perhaps be said that UKIP’s voter numbers (until recently) justified representation and since they have had no MPs (except, for a short period, Douglas Carswell and Mark Reckless, who defected from the Tories), it would be to their MEPs that the BBC would have to turn. But that doesn’t explain the absence of the MEPs of other parties. UKIP has been represented on Question Time in a staggering 24% of the programmes since 2010, compared with just 7% for the Green Party.

UKIP aside, the BBC seems to give an extraordinarily regular platform to Jacob Rees-Mogg. He is hardly the only pro-Brexit backbencher, yet his presence is ubiquitous on the BBC. Of course, he features on other news outlets as well but – again, it’s only my impression – to nothing like the same extent. In any event, there is no one individual on the Remain side to whom the BBC gives the same exposure – another subtle but significant skew towards the Brexiters.

Moreover, he, like other regularly featured Brexiters such as Iain Duncan Smith and Bernard Jenkin, is not a member of the government. The LBC presenter James O’Brien recently made the point that the government are unwilling to put up ministers to defend Brexit policy. In their absence, Brexiters outside the government get used. That is a major failure of political accountability and, as O’Brien says, it would be better to empty chair the government rather than use proxies. For that matter, if such proxies are to be used why look only to the Ultra Brexiters of the European Research Group? There are many who support Brexit in its soft variant. By ignoring them the BBC, again subtly, skews not just towards Brexiters but to the most extreme amongst them.

The BBC’s approach is a continuation of the ‘balance’ it sought to achieve in the referendum itself, where it adapted its methods of dealing with party politics, especially at elections, with the two main parties getting an equal airing. So, for every Remain statement there was a Leave response and vice versa, supposedly ensuring impartiality.

The trouble is, many technical issues around Brexit don’t sit well with normal electoral senses of balance. Taking economics, whilst it is not a precise science – if indeed it is a science at all – the overwhelming balance of opinion amongst economists, including those employed by the government, is clear: Brexit will be economically damaging and the uncertainty is the extent of the damage. Yet ‘balance’ suggests that the pro-Brexit minority of economists have equal billing with the anti-Brexit majority. This repeats the mistake made in coverage of climate change: equating balance with due impartiality (the word ‘due’ has to do a lot of heavy lifting in these debates, and lies at their core).

Beyond who is on programmes, there is also the way they are interviewed. I don’t think it is a problem in itself that journalists at the BBC or elsewhere have discernible political views. We expect them to be serious, thoughtful people and serious, thoughtful people have opinions of their own. And they are not robots, so we get glimpses of those views. I certainly don’t pretend to know for sure, but my impression is that, for example, Sky’s Faisal Islam and Jon Snow of C4 News are Remain-inclined whereas John Humphrys and Andrew Neil of the BBC are Leave-inclined.

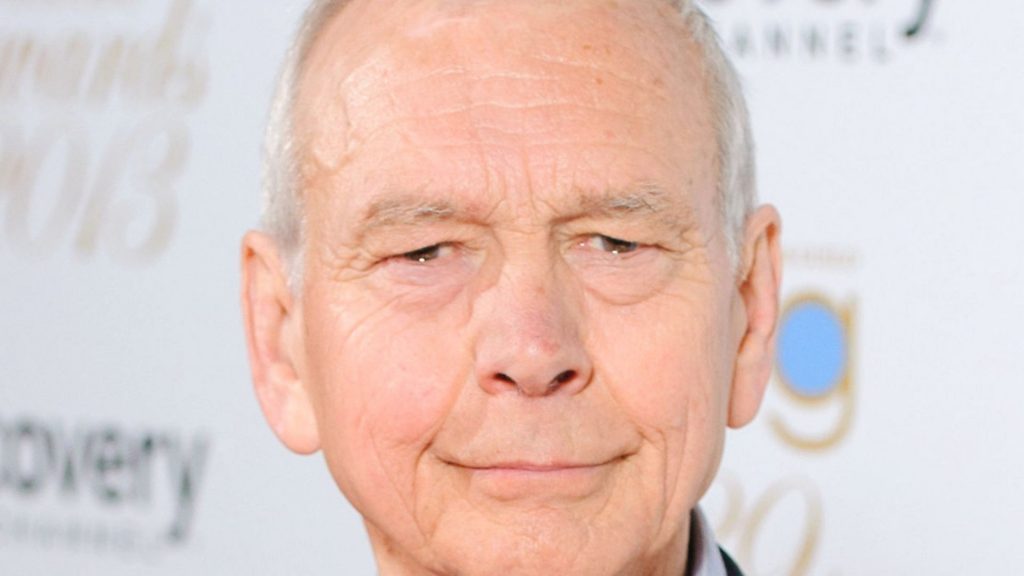

That only matters if it affects their conduct. Taking the BBC duo, I have never heard Neil conduct an interview on Brexit which is not tough and well-briefed, regardless of what side of the debate the interviewee is on. To my mind, he’s an exemplar of effective political interviewing. Humphrys, by contrast, inserts his own implicit views about Brexit rather obviously, which does affect his conduct – recent examples include his widely-complained about interview with Tony Blair and, most bizarrely, his asking the Swedish ambassador if Sweden will end up speaking German after Brexit. Humphrys has a particular importance, because he is perhaps the Corporation’s most senior journalist, and Today is an agenda-setting programme, so his conduct has a significant reputational consequence for the BBC.

But there’s another aspect which is more structural than personal. The BBC has some truly excellent journalists specialising in the EU and Brexit but the headline interviews are almost invariably conducted by generalists. Understandably, they don’t always have enough knowledge to hold interviewees to account on technical issues. To take a basic example, politicians talking – as very many do – about ‘access to the single market’ should always be, but rarely are, taken to task. Everyone has access to the single market, the issue is on what terms. The largely unchallenged use of the term has seriously damaged public understanding, since access is compatible with any and every version of Brexit, and no Brexit. Much the same applies to persistent confusions on basic issues such as goods vs services, tariffs vs non-tariffs or border control vs freedom of movement.

It might be said that the issue of specialist knowledge is as relevant for interviewing Remainers as it is for Brexiters. But, again, it’s more subtle than that. The Brexiter case is very often that it will be simple, quick and technically easy (e.g. to secure a trade deal) whilst the Remainer case is often that it will be difficult, slow and technically complicated. It’s very difficult to probe assertions that things will be simple without knowing the complexities to put the counter-case; whereas it is fairly easy to probe assertions that things will be complicated by putting forward simplicities as the counter-case. So, in this very subtle way, the high profile set-piece interviews are almost invariably easier on Brexiters than Remainers.

My sense is that over the years the BBC has been stung (or perhaps worn down) by the very vocal criticism of the anti-EU movement and of the political right more generally. Relentless accusations of liberal-left bias from the right wing and eurosceptic press, as well as from insiders, led it to a kind of ‘liberal guilt’. A criticism of cultural bias is inevitably much more difficult for the BBC to push back against than the more familiar one of being accused by this or that party of bias, something it has been robust in standing up to.

This was the backdrop to the BBC Trust’s impartiality review of 2013, with the UK’s relationship with the EU identified as one strand for review. I think that at least since then the BBC bent over itself backwards to avoid accusations of pro-EU and, now, anti-Brexit bias. But there are two problems. First, the research for the 2013 review showed that the evidence pointed in the other direction. Despite that, what seemed to persist was a sense that, even so, there was a kind of question mark hanging over the BBC; a need always to compensate for a crime even if it hadn’t actually been committed. This of course is entirely anecdotal, but friends who have worked at the BBC have told me that something like this has been the mood music in recent years. So by pushing even a little further away from anything that could be accused of being a pro-EU stance the BBC has actually become more imbalanced.

The second problem is that, despite doing this, the BBC is still accused of having an anti-Brexit bias reflecting the fact that for a very vociferous group in politics and the media anything other than uncritical cheerleading for Brexit – which I certainly don’t think the BBC can be accused of – will be regarded as bias against Brexit. A YouGov survey in February showed that 45% of Leave voters think the BBC has an anti-Brexit bias, compared with 14% of Remain voters; meanwhile just 13% of Remain voters and 5% of Leave voters think the BBC has a pro-Brexit bias. Overall, this means 27% think the BBC anti-Brexit, 8% think it pro-Brexit and 24% think it neither.

On the face of it, this goes against the argument I’m making here, but what is also shown is that 37% of Remain voters think the BBC has neither bias, compared with just 13% of Leave voters. I think that what this codes is, first, that Leave voters are likely to interpret anything that isn’t wholeheartedly pro-Brexit as being anti-Brexit and, second, that hostility to the BBC is linked with the range of socially illiberal attitudes associated in other surveys with support for Brexit. So it is likely to be an artefact of the issues underlying Brexit rather than of BBC Brexit coverage per se.

The YouGov survey also compared perceptions of the BBC’s coverage with other broadcasters and it would surely be worthwhile to undertake comprehensive research into how Brexit is covered by different networks. Of course no amount of research can provide definitive answers. The concepts of balance, due impartiality, bias are too slippery for that to be possible. Yet there seems to be a growing volume of criticism of BBC pro-Brexit bias. Some of it is aggressive and over-blown but the BBC should not ignore it all, especially when so much of it comes from its friends and defenders rather than its habitual and implacable detractors.

• This is a shortened version of an essay that originally appeared on the Politics Means Politics; find it at vip.politicsmeanspolitics.com

• Chris Grey is professor of organisation studies at Royal Holloway, University of London and writes a blog analysing Brexit, accessible via the accompanying Twitter feed @chrisgreybrexit