Peter Millar considers the unfortunate – and not uncommon – plight of those named after Europe’s dictators.

What’s in a name? Everything. Or nothing. More or less.

It was sitting in my favourite corner bar in the old town of Marbella, Andalucia, with my friend Frani, a waiter in the nearby Polaca, a bar of Polish origins (it’s a very cosmopolitan town and happy with it) when another regular, a Lithuanian, resident here for 20 years, joined us for a beer.

So far, so good. It was only when, for some reason, we got onto the origins of names that things got awkward. “Well, we know who you’re named after, and why you never use your full name,” Frani was told.

It was true, of course, which was why it was never said. Frani is 44 years old, which makes him exactly the wrong age, just old enough to have been born in the last year of the life of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, and named after him, like so many of his generation and older.

Being born under a dictatorship and given the name of the ruler is a curse that had afflicted many down the ages. Usually men, that being the given nature of most dictatorships. Spain is the most enduring example, Franco having been the longest survivor of the fascist wave that took hold of Europe in the 1920s and 1930s, only dying in 1975, much later than the others.

I know more than a few middle-aged Spanish men born ‘Francisco’ but who prefer to be called Frani, Francis, or Cisco. It is polite not to mention it. Even today Franco’s legacy is poisonous, with the debate over exhuming his body and closing his burial site and civil war monument still controversial. As recently as last month, the supreme court suspended his exhumation pending appeals by the family.

Frani took it particularly hard given that the bar where he works has – amongst photos of old Marbella, before it became a globally-known holiday resort – one that shows the ayuntamiento, the town hall, in its famous Plaza de los Naranjos (Orange Tree Square) with FRANCO in metre-high letters across the front.

There are still a few baby boys born in Italy and christened Benito, but primarily because the name means ‘blessed’ and somehow Mussolini has escaped the opprobrium of Hitler or Stalin.

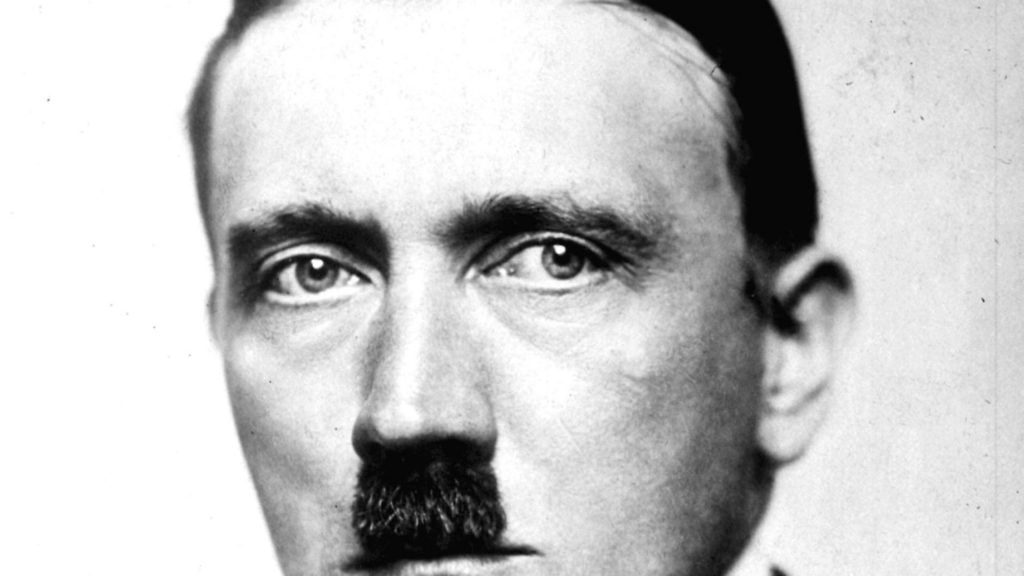

‘Adolf’ was a common name bestowed on German children born in the 1930s or earlier, but almost totally abandoned after 1945. The only other ‘Adolf’ known to most, German or not, in today’s world, slipped to fame even before the Second World War via his nickname ‘Adi’, fused with his surname ‘Dassler’ to become the sports brand he founded: Adidas.

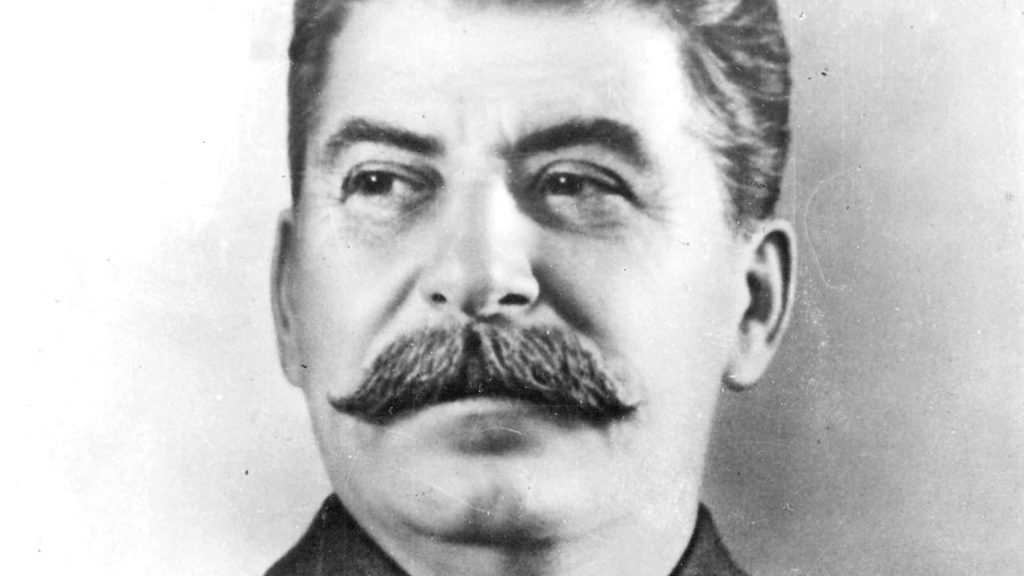

Stalin survived for a while in another form. The atheist Soviet revolution turned its back on traditional names derived from Orthodox saints. In an attempt to secularise society, it became common to give children names derived from mundane sources: examples include ‘Traktor’ for a boy, ‘Elektrificatsia’ for girl.

Even today, bizarre as they might seem in English, there are Russians with surnames that reflect the repercussions of Stalin’s purges: ‘Byeznameny’ (‘No-name’) and ‘Nyeznakomy’ (‘Unknown’).

But the most quixotic survival of the dictator’s personality cult is the first name ‘Melor’, which was originally Melsor, derived from the first letters of: Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin and Oktyabrskaya Revolutsiya (October Revolution). After Stalin’s death in 1953 and Khrushchev’s 1956 speech denouncing his atrocities, any child called Melsor was renamed Melor.

As far as politically-derived names go, Britain has so far been lucky, perhaps because it has been equally lucky in avoiding dictatorships, although there are numerous toddlers today named ‘George’ and ‘Charlotte’ after royal babies. There are also more than a few boys from the former colonies, for some reason chiefly the Caribbean, christened Winston.

Which brings me back to the other partner in my conversation in that Marbella bar. Born in Lithuania, and therefore an EU citizen long resident in Spain and a fluent Spanish speaker, but his native language is Russian. And his name is Boris. Let’s cross our fingers and hope…