Charlie Connelly looks at the life of Henry Dunant.

In 1859 Henry Dunant was in a state of excitement.

A decade earlier the 31-year-old Swiss had completed his education with modest results and joined a bank, apparently destined for an unspectacular career in currency exchange before an 1853 business trip to North Africa opened up opportunities he’d never imagined.

By the end of the decade Dunant had secured investment from friends and contacts in his native Geneva and founded his own company growing corn and trading it internationally from a large tract of land he’d secured in French-occupied Algeria. It was, he was certain, a licence to print money and he and his investors would be made for life. The problem was the project had ground to a halt over a rights dispute concerning access to the site’s water supply. Alarmed at the prospect of this golden opportunity being strangled by 19th century imperial bureaucracy, Dunant decided the best and swiftest solution to the impasse was to go straight to the top and appeal in person to the French Emperor Napoleon III.

In the early summer of 1859 Napoleon III was in Lombardy overseeing French participation in what became the Second Italian War of Independence, assisting the Piedmontese in their efforts to drive Austrian forces out of northern Italy. At the end of June the emperor had established temporary headquarters just outside Solferino, south of Lake Garda, preparing for a potentially decisive battle. Henry Dunant set out from Geneva to find him.

On June 24 an estimated 250,000 troops faced each other in sweltering heat at the Battle of Solferino. A massive Franco-Piedmontese onslaught forced the Austrians back and, despite a gallant counter-attack late in the day in the midst of an almighty thunderstorm, led to a convincing victory at the cost of 40,000 lives on both sides, one of the bloodiest battles ever fought in Europe at the time.

Dunant, still brimming with excitement at the prospect of his Algerian fortune, arrived at the nearby town of Castiglione just as the battle ended, descending from his carriage among hundreds of wounded and battle-dazed. All thoughts of finding the emperor vanished as a horrified Dunant made his way to the church determined to help. Inside he found a hellish scene: soldiers laid out on floors, pews and on top of tombs, blood everywhere and the agonised screams of the wounded echoing around the eaves. The smell, an overpowering mixture of stale sweat, excrement and infection, almost sent Dunant reeling back into the town square but, despite having no medical training, he set to work cleaning wounds, wrapping bandages around bloody limbs and talking soothingly to soldiers who were no more than boys, crying out for their mothers. He saw some terrible things.

“There is an unfortunate man a part of whose face – the nose, lips and chin – have been cut away by the stroke of a sword,” he wrote. “Incapable of speech, half blind, he makes signs with his hands, and by that heartrending pantomime, accompanied by guttural sounds, draws attention to himself. I give him a drink by dropping gently on his blood-covered face a little pure water.” Dunant stayed up all night. Daybreak brought more evidence of the scale of the carnage. “Bodies of men and horses covered the battlefield,” he wrote, “Corpses were strewn over roads, ditches, ravines, hedges and fields; the approaches to Solferino were literally thick with the dead. Anyone crossing the vast theatre of the previous day’s fighting could see at every step, in the midst of chaotic disorder, despair unspeakable and misery of every kind.” Dunant soon found himself coordinating the treatment of the wounded, enlisting the help of local people to carry injured soldiers to makeshift field hospitals regardless of whose uniform they wore. The powers of persuasion he’d intended to use on Napoleon III were instead used on the French top brass to release captured Austrian medics and surgeons to help the relief operation.

June 24, 1859, and its aftermath changed Henry Dunant forever. He returned to Geneva traumatised. Whenever he tried to concentrate on his Algerian problem he just heard the cries of the injured and dying all over again.

So, he began to write. He wrote down everything he’d witnessed, hoping to do justice to the men he’d assisted and the men he was too late to assist. As he wrote he felt increasingly at a loss to explain why it had fallen to him, a businessman with no connection to the conflict, to coordinate the treatment and care of the wounded. An idea began to form in his mind for an international organisation that would tend to those wounded in battle, an organisation entirely neutral and respected as such by all sides in every conflict across the globe.

“All that is necessary,” he wrote, “is a little goodwill on the part of some honourable and persevering persons.”

In 1863 he published Un Souvenir de Solferino, ‘A Memory of Solferino’, an account of his experiences and a manifesto for a pan-national humanitarian organisation to save lives on the world’s battlefields, no matter their nationality, no matter their cause. Published initially at Dunant’s own expense the book caused a sensation and prompted an international conference in Geneva.

Thanks in the main to intensive lobbying by Dunant, representatives from 16 nations attended a three-day event organised by the Swiss government leading to the signing of the first Geneva Convention in 1864, guaranteeing the humane treatment of combatants wounded in battle and recognising a neutral organisation permitted to care for them whose personnel would be recognisable by their insignia – a red cross on a white background.

In the meantime, Dunant had spent so much time and money on his extraordinary humanitarian efforts that his neglected business in Algeria inevitably suffered. In 1867 he was declared bankrupt and so many investors lost money that he was effectively shunned by Geneva society, forcing him into a peripatetic life of penury. Dunant lived for periods in towns and cities across Europe from London to Cyprus, so poor he often had to sleep on the streets, until in 1887 he arrived, exhausted and in poor health, at the Swiss village of Heiden. He would never leave. As far as the world was concerned, while the organisation he founded went from strength to strength Henry Dunant had disappeared.

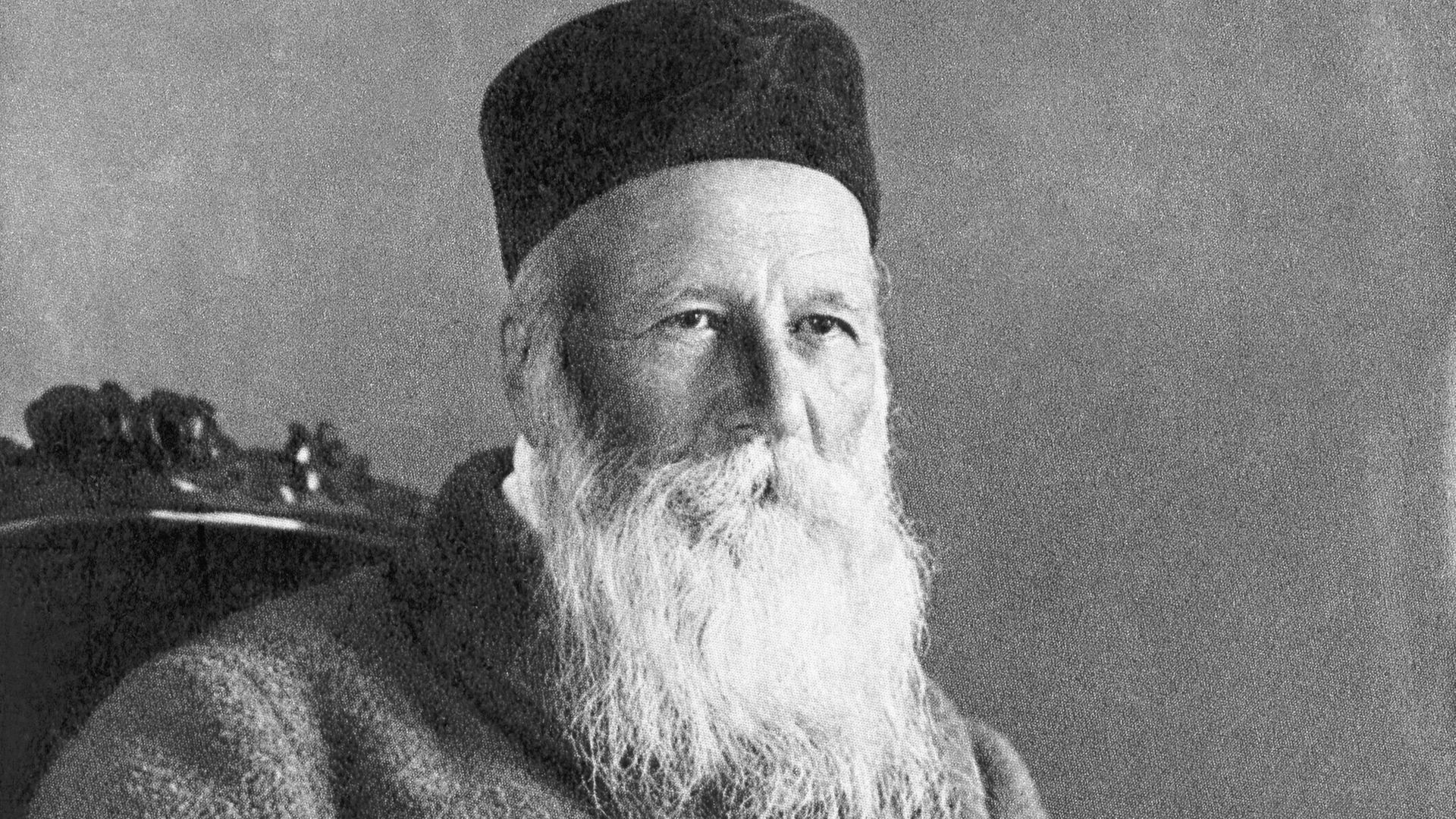

In 1890 a Heiden schoolteacher named Wilhelm Sonderegger heard from his pupils about the kindly old man with the black cap and long white beard who said he had started the Red Cross. Sonderegger did his best to alert the organisation to the circumstances of their founder and helped Dunant begin writing again, but it wasn’t until a chance 1895 encounter in a Heiden park with a journalist named Georg Baumberger that something approaching the public rehabilitation of Henry Dunant began. Baumberger’s piece for a regional Swiss newspaper was picked up by other publications across Europe and led to philanthropic donations that lent Dunant a small measure of financial security.

By then in poor health, Dunant was living in room 12 of the Heiden cottage hospital. It was there he began to receive letters from around the world praising and thanking him for his pioneering humanitarian work. There was even the occasional admiring visitor, and it was there in 1901 that Dunant received news he was to be awarded the first Nobel Prize for Peace, jointly with the French pacifist Frédéric Passy.

“There is no man who more deserves this honour, for it was you, 40 years ago, who set on foot the international organisation for the relief of the wounded on the battlefield,” read the citation. “Without you, the Red Cross, the supreme humanitarian achievement of the 19th century, would probably have never been undertaken.”

Dunant, after so long in the wilderness, must have had mixed feelings hearing such platitudes. He was old, still heavily in debt and in declining physical and mental health. He spent none of the prize money and none of the donations he received beyond covering his living expenses.

When he died in 1910 at the age of 82 he was buried without ceremony, as per his wishes, “like a dog”. For all the good he’d done, the lives he’d saved, he could never stop hearing the agonised cries of the soldiers of Solferino. He was no better than them and deserved no better grave than them. “Do not look for his name in the biographical dictionaries or lists of illustrious contemporaries,” wrote essayist Jules Claretie of Dunant’s Nobel award. “He has killed no-one, insulted no-one, injured no-one, hated no-one. Gently and silently he has upset the world, softened war and accomplished a work of immense pity.”