CHARLIE CONNELLY on a new novel about a Stasi agent immersed in the chilling oppression of the East German state, right up until its final moments.

A few years ago I was in Leipzig with a film crew. We were being taken around the city by a local fixer called Tomas, a giant of a man but warm and gentle, softly spoken with kind eyes of the palest blue. We’d pull up outside another location on our itinerary – most likely connected to Bach – and Tomas would go ahead and talk to the people inside while we removed flight cases and tripods from the back of the van and prepared to disrupt everything and everyone around us for the sake of a few seconds’ footage while Tomas kept everyone happy. Everyone loved Tomas.

Towards the end of the first day we parked outside a building on the corner of a square, a building with a rounded doorway that gave it its name, Runde Ecke, ’round corner’. The Runde Ecke was once the local headquarters of the East German secret police, the Stasi, and is now a museum. For us it was just another place to tick off the list, another session of unloading and unpacking before putting everything away again and doing the same thing somewhere else.

We had set off up the steps when I noticed that Tomas was missing. As the others disappeared through the doors I looked round and saw him still standing by the van, looking up uncertainly towards the building. Trotting back down the steps I asked if he was OK. He looked very pale.

‘That building…’ he said, and paused. ‘When I was growing up it was a terrifying place. People went in through those doors and sometimes they never came out again. Friends of mine. I don’t think I can go in there. It still scares me too much. I’m sorry.’

Years after the fall of the Berlin Wall Tomas could still sense the menace, the darkness, the danger epitomised by a building that once housed the secret police, and it still activated something deep within him. The Runde Ecke is in a prominent location at the corner of one of Leipzig’s busiest squares and Tomas passed it all the time but it still triggered deep-seated fear.

He’d already told me about how he’d been part of the mass protests held in the square in 1989, demonstrations that helped to kickstart the movement that eventually brought down the Wall, describing how military police would charge through the crowds beating protesters indiscriminately, himself included.

If seeing the building at the heart of the terror was bad enough, the thought of going through its doors was too much for him to bear.

I left Tomas in the van and went inside. The display cases were filled with some of the equipment and techniques with which the Stasi monitored every aspect of the lives of East German citizens. The cameras – including a harness designed to make its wearer look heavily pregnant with a camera fitted roughly where the navel would be – the disguises, the endless paperwork, even jars with lids screwed tight that contained the scents of the people of Leipzig: in the DDR even your very essence wasn’t your own.

I thought of this – and Tomas – as I read The Standardisation of Demoralization Procedures, the debut novel by Jennifer Hofmann.

Demoralization was what the Stasi did best. It wasn’t long into the existence of the German Democratic Republic before they realised physical torture wasn’t usually necessary. Why go to the trouble of tearing out fingernails or pulling teeth when you could break someone mentally instead? No bruises, no blood, same result.

Bernd Zeiger, Hofmann’s protagonist, is an ageing Stasi man, a career bureaucrat in East Berlin whose early promise as a secret policeman hadn’t really flourished into a steady rise up the career ladder of surveillance and oppression.

There had been two key moments in Zeiger’s working life. One was his involvement in the questioning of a physicist named Johannes Held who in the early 1960s had travelled to a mysterious research establishment in the Arizona desert whose purpose was murky but seemed to involve the paranormal and the disappearance of orphaned children. Zeiger questioned Held, who refused to divulge what he’d learned in the US, and watched as he was tortured and beaten before being placed in a mental institution. Prior to his arrest and while under surveillance Held had been moved to the apartment next to Zeiger’s and the two had become friends. At least, that’s how Held saw it.

The other landmark in his long service was authorship of a manual called The Standardisation of Demoralization Procedures, a handbook of terror, a step-by-step guide to the total mental disintegration of suspects accused of acting against the interests of the state. Everyone in the Stasi knew about it, most could quote from it, nearly all had utilised the techniques and theories contained in its pages. It was, in Stasi terms, a masterpiece.

When the novel opens in November 1989, on the day before the fall of the Berlin Wall, Zeiger is living alone and in poor health, suffering nosebleeds, seizures and blackouts, and has become preoccupied with Lara, a young waitress at the café near the office who serves him his coffee and cheese toastie. Lara hasn’t been at work for the previous month and he is beginning to wonder where she is.

Hofmann, an Austrian-American based in Berlin, constructs a convincing portrait of life in East Germany, its sights, sounds and even smells. When Zeiger makes coffee in his apartment that morning, ‘this was not coffee. It was coffee, pea flour and disgrace. This was Kaffee Mix and tasted like a nosebleed’.

He watches a pre-dawn queue already forming at the bakery opposite his apartment. ‘Limited food and people trusting strangers with the naked planes of their backs. The pinnacle of human evolution.’

What Hofmann does particularly well is evoke the banality of authoritarianism. State terror can only thrive on the depth of its bureaucracy and the DDR’s was chasmic. When Zeiger finished his masterwork, ‘it took weeks to register, validate and archive the completion of the Manual. There were forms to fill out, which required other forms to acquire, which, in turn, nobody knew how to obtain’.

When he goes to place a copy in the archive – it’s assigned to the literary fiction department, to his bemusement – he finds ‘dense, windowless rooms, populated by haggard comrades who gave the impression of having lived there since they were born. Keepers of records and posthumous fate comprised a very particular species, one bred to survive without sunlight or rest’.

Hofmann also succeeds in twisting our expectations and assumptions. Weeks earlier Zeiger had been in the café when Lara placed a hand on his shoulder, accidentally as it turns out, but he takes this as tacit permission to turn up at her apartment bearing an assortment of odd gifts. We learn he’s been spying on her for quite a while already, observing her comings and goings from the shadows.

Boundaries clearly don’t concern Bernd Zeiger. He’s creepy for a living, surveillance has become second nature, meaning that even what appears to be a lonely man reading non-existent meanings into gestures and behaviour becomes a sinister opportunity to cross acceptable lines of behaviour emphatically and with impunity.

In the hands of a less-skilled author this would have been the extent of Zeiger’s character, but of course there is more to him than that. The more we learn about the Stasi agent the more nuanced he becomes, a little bit like Stasi officer Wiesler in the 2006 film The Lives of Others.

We develop surprising sympathies for a man who on that first morning – the last to dawn on the GDR – is even intending to report his blind neighbour for listening to a western radio station he can make out through the wall.

‘It occurred to him that although he had once been a child and there had been a childhood, it was amorphous and blank, an emptiness designed to torture by vanishing,’ Hofmann writes, detailing a family background scarred by war that would not have been untypical for a man of Zeiger’s generation but which goes some way to explaining his willing absorption into a state surveillance machine.

Zeiger’s progress through the last full day of the GDR is particularly notable for how he fails to notice it’s happening. As his country and the ideology that built it crumbles Zeiger, the master of surveillance steeped in professional paranoia, remains oblivious. Granted he has other matters on his mind, the beautifully-executed plot twists and turns that link the Stasi man, the café waitress and the physicist, but it’s still extraordinary to experience one of the great historical moments of the 20th century as burbling away quietly in the background unnoticed by the man at the heart of the story. Zeiger was supposed to be at the press conference that evening where government spokesman Günter Schabowski announced the immediate suspension of travel restrictions between East and West Germany, triggering the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Hofmann’s East Berlin is brilliantly depicted, like a lighter-touch le Carré, and the more magical elements of the story are reminiscent of Spaceman of Bohemia, Jaroslav Kalfar’s terrific novel about a Czech space mission (it’s notable that Kalfar provides a cover endorsement). The Standardisation of Demoralisation Procedures is a compelling debut, striking a perfect balance between humour and the horrors of life under a totalitarian regime even as it crumbles. It’s a novel of secrets, betrayals and how the past lurks permanently in the present.

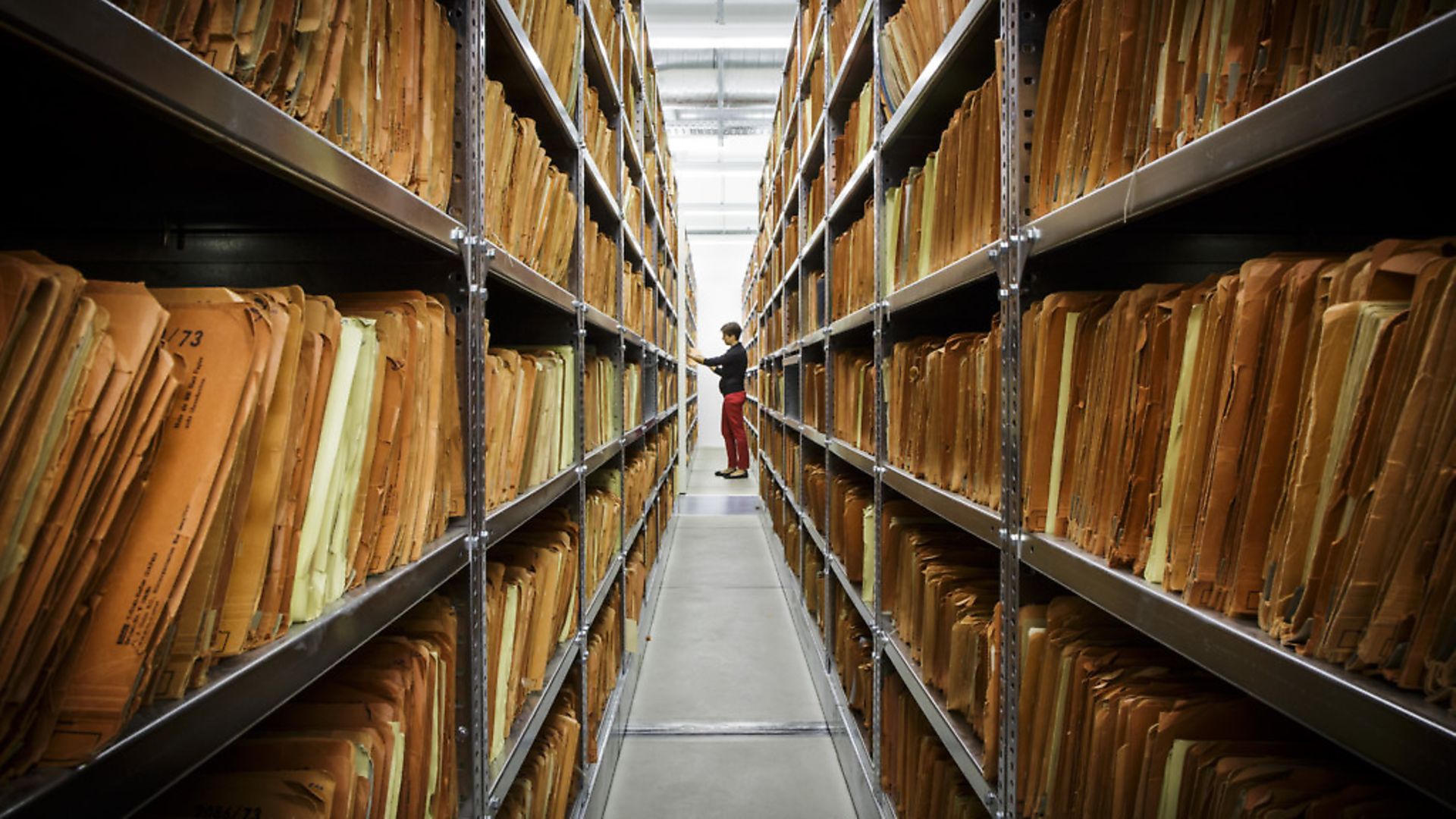

In Leipzig, in the part of the Runde Ecke that isn’t taken up by the museum, the Stasi’s meticulously kept records are available to view. People can read their own surveillance files, in some cases a day-to-day account of their activities, the places they went, the people they met, even transcripts of long-forgotten conversations decades old.

They can see photographs of themselves, capturing moments when they thought they were alone, the realisation that personal intimacy, daydreams, reflections, were the property of the most advanced and embedded surveillance state in the world.

As we drove away from the Runde Ecke I asked Tomas if he’d read his own file.

‘No,’ he replied, ‘and I never will. I never want to know which of my friends were informing on me.’

Hofmann’s novel distils beautifully much of what millions of Tomases went through during an era where any kind of free will or even basic hope must have seemed pointless.

‘Numbing yourself makes some people fearless,’ says Dr Witzbold, the ennui-riddled psychiatrist assigned to Johannes Held. ‘Others it turns into murderers.’

The Standardisation of Demoralization Procedures by Jennifer Hofmann is published on August 11 by Riverrun, price £16.99