For centuries the French capital has been a centre for freedom of expression, a status that has produced legendary artists and venues. SOPHIA DEBOICK reports

Paris is where legends are made. Or rather where they make themselves. The icons of French music have routinely spun mythical backstories for themselves, and the very streets of the capital hold such a totemic power that some have claimed to have been born directly onto them.

Édith Piaf maintained her mother gave birth to her on a policeman’s cloak on the pavement outside number 72 Rue de Belleville. In 1969 the ‘French Elvis’, Johnny Hallyday, released a self- mythologising single which began “Je m’appelle Jean-Philippe Smet /Je suis né à Paris /Vous me connaissez mieux sous le nom de Johnny / Un soir de juin en 1943 je suis né dans la rue” (“My name is Jean-Philippe Smet/ I was born in Paris/ You know me better under the name Johnny/ One evening in June 1943 I was born in the street”).

In an epic bit of name-dropping and further image enhancement, Hallyday claimed in his 2013 autobiography that a 44-year-old Piaf felt him up at a dinner when he was still a teenager (“I ran away from Piaf. I was almost a virgin at the time. I couldn’t see myself in bed with her. As far as I was concerned, she was an old woman”). And these two Parisian icons were thus bound together in a scene that summed up the recurrent themes of the music of Paris – heartbreak, hedonism, seediness, pathos, sex and the surreal.

In Paris’ Belle Époque, those elements ran riot in what was a dazzling entertainment city. From street singers to the top-billed names of the grand music halls – the Folies Bergère, Alcazar, Alhambra, Bobino and Bataclan – there was music everywhere in this pre-First World War period. The city’s café-concerts (caf’conc’) included almost every type of performance, but chanson réaliste was the most engaging, as singers explored the romances and compromises of working-class life in risqué, subversive and satirical songs.

Chanson réaliste was pioneered by songwriter and performer Aristide Bruant – immortalised in red scarf and black wide-brimmed hat in Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters of the 1890s – at Montmartre’s Le Chat Noir cabaret, a breeding ground for all that was innovative in turn-of-the-century Parisian music.

Éric Satie cut an unassuming figure as the in-house pianist there between 1899-1911, but he had already produced his masterpiece, the extraordinarily delicate Gymnopédies, the zero point for ambient and minimalist music. These works were a world away from the spirit of the cabaret and the music hall, but that was really the point of Belle Époque Paris, where the high and low, in terms of both art and society, mixed freely. After all, Satie’s friend Debussy, born on the fringes of Paris, was a Le Chat Noir regular even as his music was celebrated in high society.

In the latter half of the war that was devastating Europe, and into the Années folles (‘crazy years’) of the 1920s, it was a jazz rhythm imported from across the Atlantic that Paris throbbed to. What was often branded degenerate in its birthplace was revered as true musical art in Europe, the jazz sound dovetailing with the cabaret format and hedonistic spirit of the French capital in the acts of the black Americans Josephine Baker and Ada ‘Bricktop’ Smith (Baker would sing “J’ai deux amours, mon pays et Paris” [“I have two loves/ My country and Paris”]), and in Lower Montmartre’s Pigalle district, black American jazz began to be fused into the city’s DNA as it was taken up with passion by the natives.

Charles Delaunay, a son of artists who grew up immersed in the avant-garde, became the leading champion of jazz in the city, founding the Hot Club de France and the magazine Le Jazz Hot in the mid-1930s and assembling the Quintette du Hot Club de France. The quintet featured violinist Stéphane Grappelli and legendary Django Reinhardt, whose jaunty, carefree guitar became the sound of mid-century Paris.

While the Nazi occupation stifled this swinging jazz scene (Delaunay became a Resistance man; Reinhardt, at serious risk as a French Romani, tried to get out of the country in vain but managed to survive; Grappelli sat it out playing jazz in London) after the war it entered a new era.

Le Tabou club in Saint-Germain-des-Prés was the place to be in post-war Paris. The favourite haunt of the existentialist philosophers, it opened in 1947 and became a haven for jazz, with a house band led by trumpeter, novelist and jazz champion, Boris Vian. With Delaunay also launching a jazz festival in the city before the 1940s were out, attracting the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Sidney Bechet and Miles Davis (all finding an acceptance in Paris that they could only dream of in a US riddled with racial prejudice), Paris became one of the jazz centres of the world.

By the time Piaf recorded her signature Non, je ne regrette rien in 1960, right at the end of her career and her life, Paris had gained a troupe of chansonniers destined for similarly legendary status. Most had made their first professional moves in the 1940s, having fought, laboured, resisted or otherwise ducked and dived to survive the war, going on to demonstrate the French aptitude for both sardonic wit and tender romanticism in their songs, frequently writing and singing of the capital.

The Italian-born actor and singer Yves Montand had been mentored by Piaf, and his version of À Paris (1951) – a series of vivid snapshots of the capital which, with characteristic emotional oscillation, included both enraptured lovers and prospective suicides walking by the Seine – was a classic of chanson parigote (Parisian chanson).

His contemporary Charles Aznavour’s La bohème (1965) was a lament for the Montmartre of his youth, while the decade older Charles Trenet, who made a comeback in the 1950s, had sung nostalgically of the Ménilmontant neighbourhood in a swing and jazz-influenced song of that name of 1938 (“Ménilmontant mais oui madame/ C’est là que j’ai laissé mon cœur” [“Ménilmontant, but yes ma’am / That’s where I left my heart”]).

Gilbert Bécaud, who was a member of the Parisian Resistance and went on to write with Aznavour and for Piaf, was one of this cohort, as was Georges Brassens, who made his debut in 1952 with La mauvaise réputation, a song about non-conformity that was reflective of his politics.

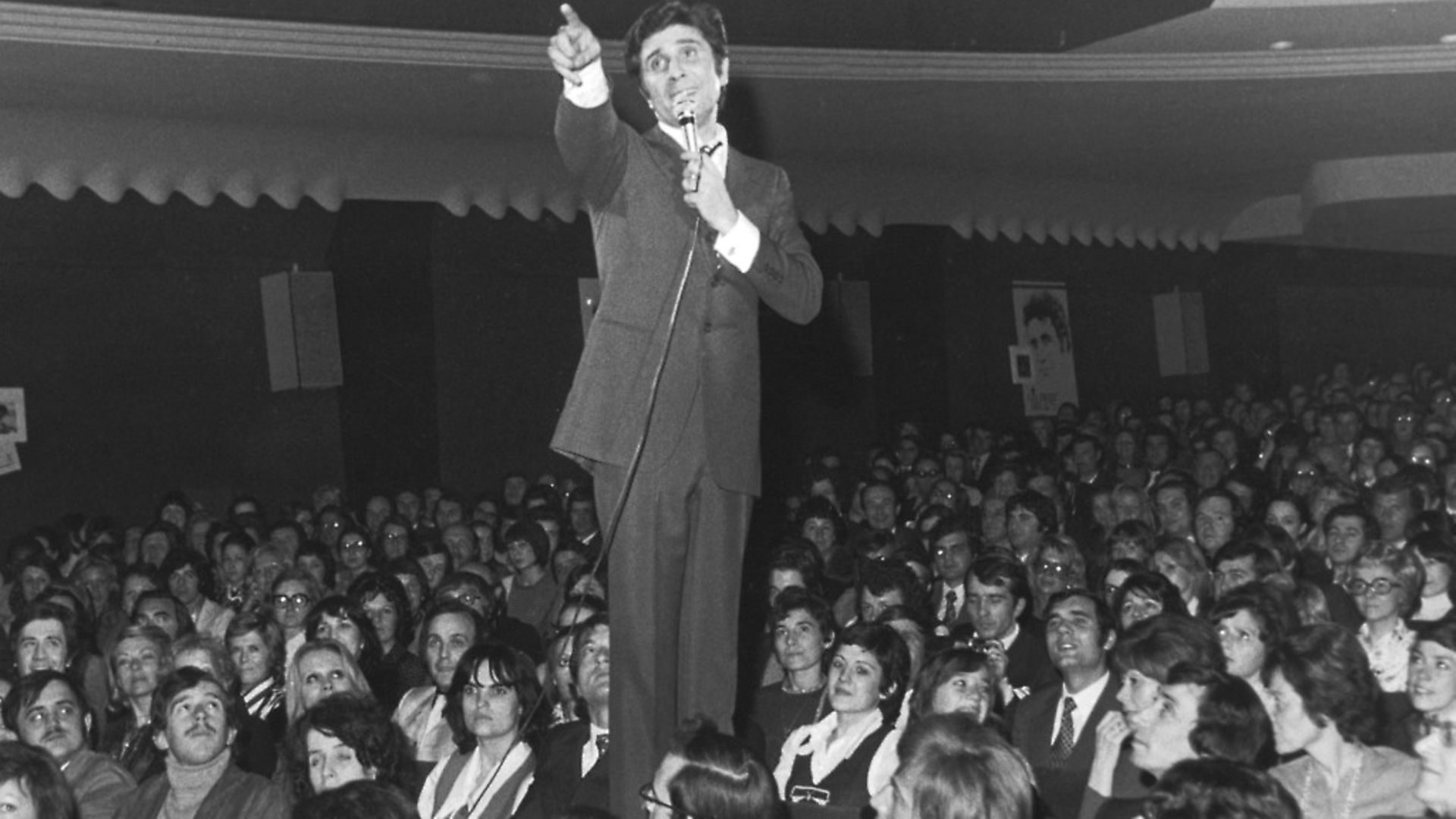

Similarly barbed was much of the work of the younger Jacques Brel (witness 1961’s Le moribond, which deftly covered anti-clericalism, marital infidelity and existential regret). Brel arrived in Paris from his native Belgium in the early 1950s, debuting at the Olympia in 1954 and living in the city’s eastern suburbs until his early death. The image of the bold-featured Brel sweating under the lights of smoky clubs during his histrionic cabaret act is as Parisian as the Eiffel Tower.

These legendary figures continued their careers into the 1960s as elder statesmen, even as a new sound exploded out of Paris. Gilbert Bécaud inadvertently gave birth to the new yé-yé sound when his song, Salut les copains, was taken up as the title of the radio show and magazine that launched this French pop movement.

Johnny Hallyday may have been the king of yé-yé, but it was a clique of Parisiennes who dominated the genre. There was the enigmatic Françoise Hardy, with self-penned songs as well as ones written by her artistically versatile future husband, Jacques Dutronc (his dreamlike yet slightly unnerving Il est cinq heures, Paris s’éveille [1968] is notable for its impressionistic picture of the city in the early hours of the morning). France Gall, meanwhile – the teenage muse of Serge Gainsbourg, who wrote the 1965 Eurovision winner for Luxembourg, Poupée de cire, poupée de son, for her – was the ultimate pop ingenue.

Adopted Parisiennes loomed no less large in yé-yé. Bulgarian-born Sylvie Vartan moved to Paris as a child and was a glittering personality both as an energetic interpreter of Anglophone hits and half of the ultimate French music power couple as Johnny Hallyday’s wife. The Italian diva Dalida had already had massive success by the time yé-yé came round, but changed her sound to exploit it, with her cover of Itsy bitsy teenie weenie yellow polka-dot bikini becoming a huge hit in the summer of 1960. Brit Petula Clark, having married a Frenchman and settled in Paris, embodied the spirit of yé-yé with 1962’s Ya Ya Twist, among other records. It all added up to mini-skirted fun that tried to imitate the bubblegum side of Swinging London, but outdid it by taking itself rather less seriously.

Fast forward to the end of the century and French house was exporting pure hedonism from Paris. Between the mid-1990s and the early 2000s, Parisian duos Daft Punk, Stardust (both projects of the visionary Thomas Bangalter), Modjo and Cassius released mega-smash, disco-inflected singles with a distinctively French flavour which took the world by storm. Later, from that scene emerged Paris-born David Guetta, a titan of electronic dance music and all-consuming music industry giant today.

Yet, for all this recording success, it is Paris’ live venues that really retain the spirit of its musical history, and while its dance club scene lags behind the likes of Berlin, its rock venues remain names to conjure with. The 2015 terrorist attack on the Bataclan only underscored how, in a fact unchanged in the 150 years between the venue’s opening at the height of music hall and the time of the attack, that music always means freedom in Paris – freedom of expression, emotion and enjoyment.