The mid-90s saw the triumph of two very different double acts – Robson and Jerome and the Gallagher brothers.

Robson and Jerome – the stars of ITV’s military drama Soldier Soldier – double A-side Unchained Melody/(There’ll Be Bluebirds Over) The White Cliffs of Dover was the bestselling single of the 90s until the release of Elton John’s 1997 tribute to Princess Diana.

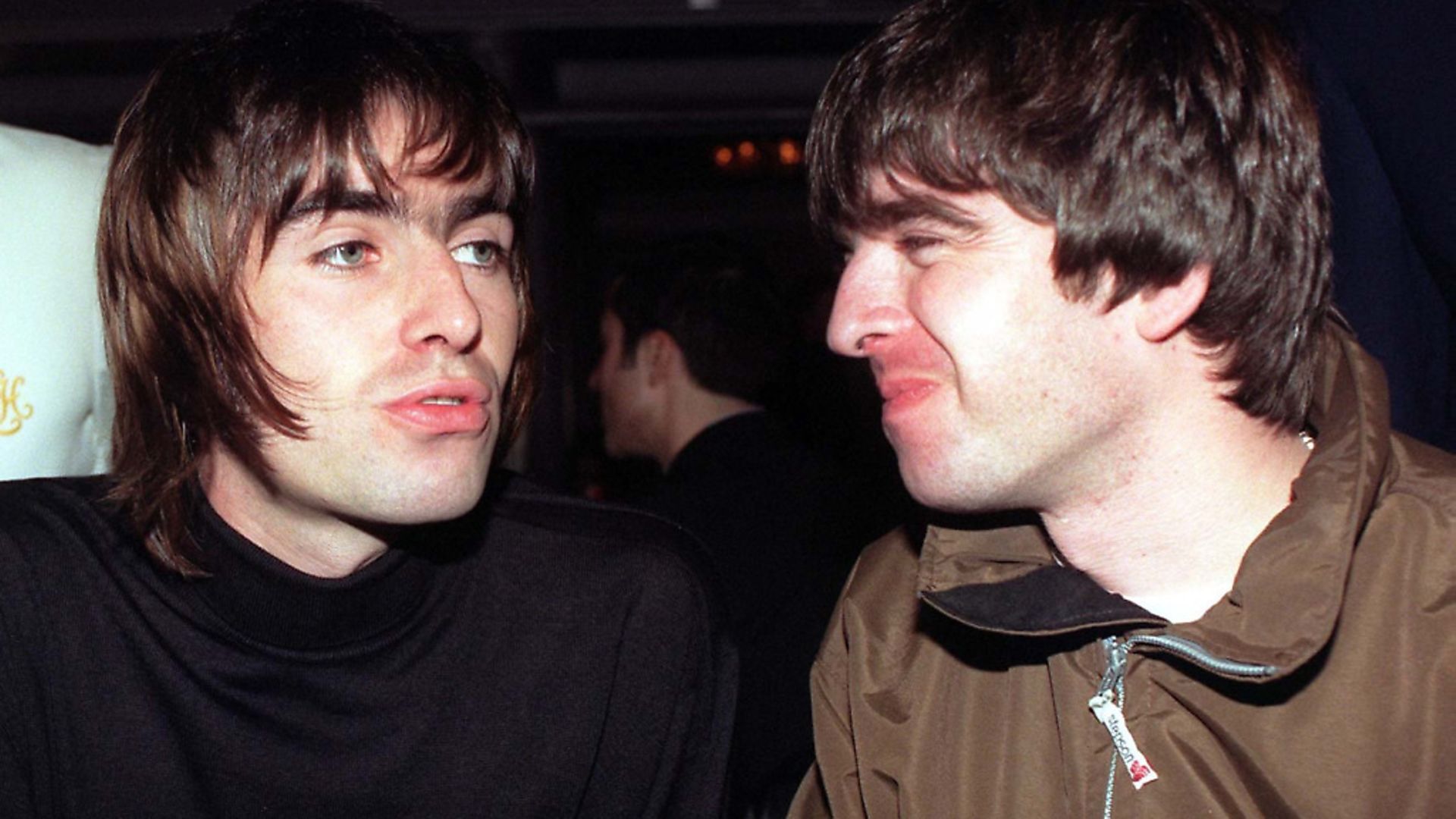

Meanwhile, Oasis vied with Blur for the status of kings of Britpop (both had a number one single and number one album that year).

A mod revival was in progress and the celebration of a quaint, largely fictional, Englishness, was in vogue. While Robson and Jerome would seem to have little in common with this movement, both were marked by an uncritical nostalgia in this, the flag-waving 50th anniversary year of VE Day.

And, as much as the nation was looking back, it was also looking forward, with an optimism that is barely imaginable in today’s political landscape. But Britpop was not all Union flag guitars and nationalistic bravado. It also accommodated more diverse ideas of Britishness and wilder aesthetics than those of the Gallaghers and it existed alongside a wealth of other genres at a time when British popular culture was rich, varied and ever-innovating.

Britpop could only have existed in the pre-internet, pre-streaming age, when albums still sold. Even minor Britpop bands held their own on the album chart against the monster acts of that year, Celine Dion, Mariah Carey, Bruce Springsteen, Bon Jovi and Michael Jackson. Punky, female-fronted Elastica and former shoegazers The Boo Radleys, as well as Pulp and Supergrass, had chart-topping albums that year.

The remnants of the baggy scene, in the shape of Black Grape and The Charlatans, as well as ‘Modfather’ Paul Weller, also had hit LPs. Britpop was a mass movement then, and ‘The Battle of Britpop’, when Oasis’ Roll with It and Blur’s Country House went head-to-head for the top of the singles charts, was of national interest. This battle had been engineered by a weekly music press which too couldn’t survive the internet age. Melody Maker and the NME followed the soap opera of the incestuous Britpop world in painstaking detail, Camden boozer The Good Mixer being the infamous centre of much of this activity.

A new beast in print media was also crucial for Britpop – the lads’ mag. Loaded had been launched and FHM rebranded the previous year, with the latter beginning its trademark 100 Sexiest Women poll in 1995. The Neanderthal impulse was never far away from Britpop, and despite the claims to an authentic vulgarity versus these soft middle class southerners, the studied blokeish swagger of the Gallagher brothers was outdone by Blur’s lazy retro-sexism in their Damien Hirst-directed, Benny Hill-inspired music video for Country House. Meanwhile, chronicler of the man-child Nick Hornby published his debut novel High Fidelity, and the video for Supergrass’ Alright, reaching number 2 in the charts that summer, featured the teenagers larking about on Portmeirion beach, channelling the cartoonish mischievousness of The Monkees in full technicolour.

Yet for all the deliberate lack of sophistication of much of Britpop, there was an underbelly of bands who engaged in darker, more mature lyrical themes, took glamour seriously and rejected the unreconstructed masculinity of the genre’s leading lights. Suede’s Brett Anderson was the most fey frontman in pop history, and his lyrics depicted a Britain of disaffection and alienation. Macclesfield band Marion, fronted by the impossibly beautiful, golden-voiced Jaime Harding, were set for big things before his drug addiction hamstrung them. Harding was a Melody Maker cover star in April 1995, with the magazine asking if they were ‘A Joy Division for the Nineties?’ Marion had toured with boarding schoolboys Radiohead, who released the atmospheric and tortured The Bends in 1995.

Meanwhile, The Manic Street Preachers, in their early leopard-skin and eyeliner incarnation, declared themselves out of the Britpop game before it even really began, with 1994’s The Holy Bible exploring prostitution, murder, anorexia and genocide and lyricist Richey Edwards disappearing in February 1995. Their return as a three piece the following year with the hit album Everything Must Go saw them catch the tail end of the Britpop movement. Sheffield’s Pulp, formed some 17 years before, continued to plough their own furrow with their northern kitchen-sink realism transposed into catchy pop. Common People was a top ten single, and Jarvis Cocker, a lanky 6ft 2in and a good decade older than the competition, was an intriguing proposition as a pop star. London band Menswear entered the scene as extras in a Pulp video and exited it vilified as lightweights, but their PR strategy of shamelessly faking it till you make it made them one of the most fascinating acts of the year. They appeared on Top Of The Pops and the cover of Melody Maker, which proclaimed them ‘the best-dressed new band in Britain’, before they had even released any material.

Pulp, Marion and Menswear were all stars of the TV event of the year, as far as music was concerned, BBC2’s Britpop Now, aired just two days after the release of the Battle of Britpop singles, when Take That’s emotional farewell, Never Forget, was still at number 1. Damon Albarn acted as gatekeeper for this showcase of 13 bands, with neither Oasis nor Suede invited (Brett Anderson was the former partner of Elastica frontwoman Justine Frischmann, then Albarn’s girlfriend), and Britpop’s reactionary side was in evidence in Albarn’s introduction to the programme, where he figured the movement as an anti-grunge and, therefore, necessarily anti-American, crusade. He complained ‘Nirvana, Nirvana, everywhere Nirvana. America had found a voice and a face capable of expressing its anxiety and self-loathing … If America felt like this, then the whole world had to feel the same way’, suggesting the acts that followed were valiant resisters of cultural imperialism.

But Albarn’s snobbery was not echoed by public tastes and festival season during the uncommonly hot and dry summer saw a defiant showing for grunge bands, more than a year after the suicide of Kurt Cobain. Britpop Now’s Gene, Menswear, Marion, Powder, Echobelly and The Boo Radleys all appeared at the Reading Festival, taking place two weeks after the show aired, but grunge giants Soundgarden, Mudhoney, Smashing Pumpkins and Pearl Jam (backing Sunday night headliner, Neil Young) got a rapturous reception on the main stage. Cobain’s widow Courtney Love’s band Hole attracted huge interest and thousands tried in vain to get into the Melody Maker tent to see the Foo Fighters, the new project of Nirvana drummer, Dave Grohl. Oasis headlined Glastonbury and the festival’s NME stage was dominated by Britpop, including Sleeper and Supergrass, but new genres were also out in force, with Tricky and Massive Attack representing trip hop in the year Portishead won the Mercury Music Prize.

Political change was brewing in 1995. In June, John Major resigned as Tory leader in an attempt to strengthen his authority. He slaughtered John Redwood’s challenge in the leadership election that followed, a proxy battle between Europhile and Eurosceptic Tories, and indeed the EU was in the ascendant, with Austria, Finland and Sweden joining, the Schengen Agreement coming into force and Romania, Slovakia, Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania all applying to join. The pro-EU Tony Blair was also waiting in the wings, and it was at Labour’s special Easter conference that he took the party to the centre and New Labour was born when the nationalising principle of Clause IV of the party’s constitution, stating the aim ‘to secure for the workers … the common ownership of the means of production’, was replaced with a more general aim to create a society where ‘power, wealth and opportunity are in the hands of the many, not the few’. Blair would later reap the rewards of the Cool Britannia concept that Major had tried to take credit for, culminating in the spectacle of Noel Gallagher sipping champagne at Downing Street following the Labour landslide.

This year also saw the consolidation of the group of artists known as the YBAs (although the term ‘young British artists’ would not appear until 1996), through the Brilliant! exhibition in Minneapolis at the end of the year. Rachel Whiteread, Jake and Dinos Chapman, Sam Taylor-Wood, Gillian Wearing, Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas and Damien Hirst all featured, and Hirst would win the Turner Prize at the end of the year, beginning his dominance of the contemporary art scene. British designers were no less dominant on the Paris catwalks (and the Eurostar services from Waterloo that had launched in November 1994 made it all the easier for them to get there), with John Galliano installed at Givenchy.

He was soon to be replaced by Lewisham’s own Alexander McQueen and Stella McCartney graduated from Central Saint Martins that year, her friends Naomi Campbell, Yasmin Le Bon and Kate Moss modelling at her graduation show.

Much of the year’s television and film was as invested in nostalgia and Britishness as Britpop. There was the return of James Bond after six years with GoldenEye, Ian McKellen’s Richard III, and quintessential Englishmen Richard E Grant and a post-Four Weddings and a Funeral Hugh Grant in anodyne star vehicles Jack and Sarah and The Englishman Who Went up a Hill but Came down a Mountain.

Grant also appeared with Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet in Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility and in another Austen adaptation on the BBC, Colin Firth emerged from a lake in a wet shirt as Mr Darcy and became an instant sex-symbol. In November Bet Lynch left Coronation Street after 25 years and Princess Diana revealed all to Martin Bashir.

Meanwhile, Chris Evans, host of the Radio 1 Breakfast Show, was engaging in anarchic antics on Channel 4’s Don’t Forget Your Toothbrush, and while The Word finished its run, it was replaced the following year by a new generation of youth TV, from teatime TFI Friday to X-rated The Girlie Show.

With the launch of the Spice Girls in the summer of 1996, and the final crystallisation of Cool Britannia in Geri Halliwell’s Union flag dress at 1997 Brits, Britpop was over. Oasis, for one, had certainly reached their peak, playing to quarter of a million over two nights at Knebworth in August 1996, and many of the promising bands of the genre fizzled out after one or two albums.

The 1997 election marked the beginning of a new era, and the emergence of Radiohead as a real power to be reckoned with the release of OK Computer the following month indicated a turn to the earnest in popular music (Coldplay had formed in 1996 and would soon sweep all before them in this regard). But for pure novelty and drama, Britpop was a scene that hasn’t been beaten since.

Dr Sophia L Deboick is a historian of popular culture. Follow her @sophia deboick