The problem is that these days, it’s not the physical danger that usually brings about a fear – or panic attack – but an emotional one.

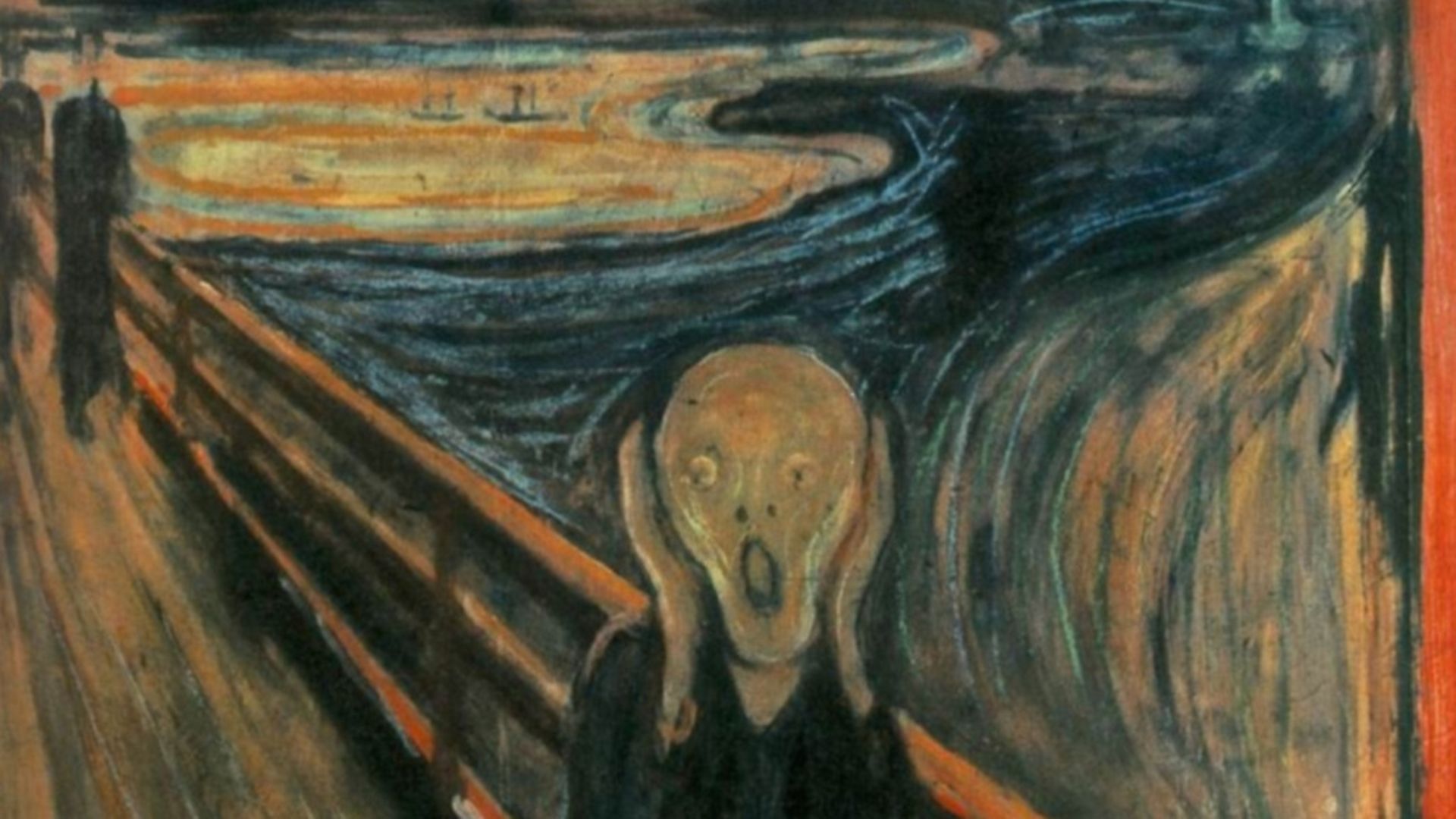

Fear: don’t you just hate it? That gnawing anxiety attacking your belly and bowels, those sweaty palms, inability to focus, broken sleep? We’ve all read about what’s going on in our bodies and brains: neural pathways that run from the depths of the limbic system to the prefrontal cortex and back become electrically or chemically stimulated and so we feel the fear.

It’s perfectly normal to have this response: our bodies, which have developed over 10s of 1,000s of years, evolved to deal with present danger – say, a passing predator – with the fight or flight response, flooding our bodies with the hormone adrenaline to power action. The problem is that these days, it’s not the physical danger that usually brings about a fear – or panic attack – but an emotional one.

Some insects, birds and mammals emit pheromones to defend themselves and warn others of their species that danger is around the corner. We humans, at the top of the evolutionary pile, have come up with new and more insidious ways of keeping ourselves on edge, like 24 hour news and social media.

Mental health blogger and singer-songwriter Leanne Brookes spoke for many when, last autumn, she wrote on the welldoing.org site: ‘Terrorism, mass shootings, political murders, Brexit, a country divided and a world in peril. Events in the news turn social media feeds into scary, hateful, sad places to be. It is hard not to stay glued to it though, involving myself in the narrative, disappointed and afraid. I have, in the end, had to unfollow news organisations which although I usually found interesting, just kept churning out fearful articles and predictions for the future which encouraged my anxieties and depression.’

Her response is understandable: for people who know they have irrational fears and are prone to anxiety and depression, most professionals would counsel them to turn away from the things that spark their fear responses. But what about when fear is a perfectly normal, rational response? Like the way the world is turning these days?

Consider recent events: an Assad-sanctioned chemical weapon attack, followed by 59 missiles from the US in return; the ‘mother of all bombs’ being dropped by the US on ISIS territory in Afghanistan; China’s foreign minister Wang Yi warning that ‘conflict could break out at any moment’ over US concern at North Korea’s nuclear testing. It’s no surprise that Google have let it be known that the searches for terms ‘World War 3’ and ‘Trump War’ have sharply escalated in he past few weeks.

Meanwhile, Theresa May and her Brexit trio have failed to shift EU leaders who want to block any talks about a future comprehensive trade deal until the UK agrees to settle its divorce bill – which could be as high as €60bn – and comes to a settlement on the rights of EU citizens.

In the meantime, those EU citizens are just one of the groups who understandably fear what the real effects of Brexit will be. Having to wait to see what that will be does nothing to calm the rising panic – particularly with all the uncertainty of a general election to prolong the process.

Cortisol, another of the hormones in the brain, is great for invoking a sudden fear response, but you don’t want it hanging around as you stew on the Brexit problem. Too much cortisol can suppress the immune system, increase blood pressure, decrease libido, contribute to obesity and more. It’s even been seen as a potential trigger for mental illness and decreased resilience.

Be worried, sure, but also be calm. And if that won’t come naturally take some exercise (kick-boxing anyone?) try mindfulness meditation, or simply hang out with friends and have some fun. You might spend some of the time moaning – you are a ‘Remoaner’ after all. But there’s bound to be good times too.

Louise Chunn is the founder of find a therapist platform welldoing.org, and former editor of Psychologies magazine