Twenty five years after a court ruling relating to an obscure Belgian midfielder transformed football here, is Brexit is about to reverse some of the changes? ROGER DOMENEGHETTI reports.

In an era when footballers have the freedom to force moves between clubs and demand multi-million-pound salaries, it’s easy to forget that as recently as the early 1990s they were still effectively treated like livestock. An anachronistic transfer system, parts of which remained unchanged for a century, meant they could not join a new club unless a fee was paid. All of that changed 25 years ago thanks to a journeyman Belgian professional called Jean-Marc Bosman.

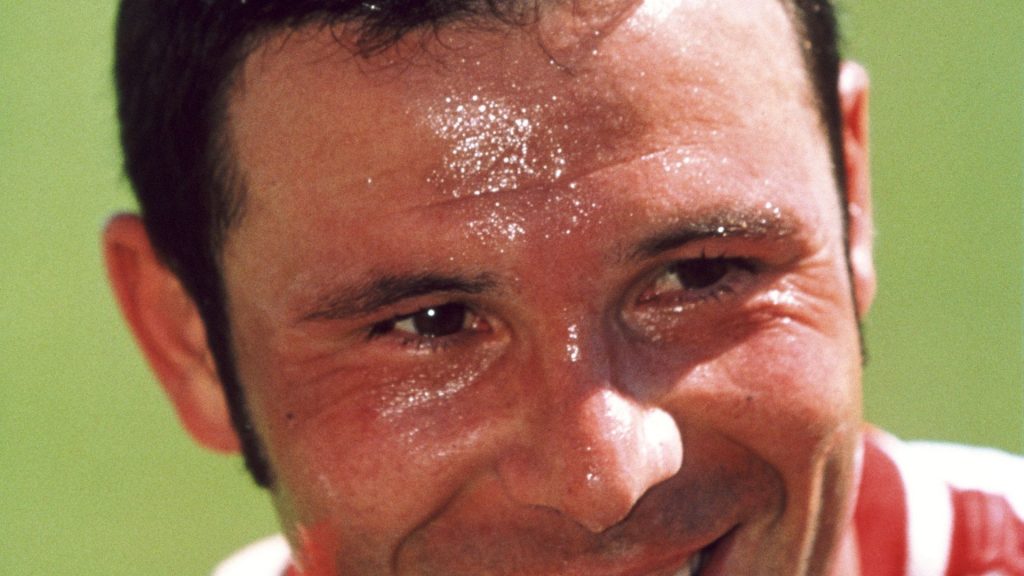

A promising midfielder, Bosman captained the Belgian under-21 team in the 1980s, but his professional career had not fulfilled that early potential. In 1990, aged 25, he was coming to the end of a two-year contract at Royal Football Club de Liège, which was worth about 120,000 Belgium francs per month (£2,000). The club offered him a new one-year contract worth just 30,000 Belgium Francs per month (£500), the lowest they could offer under the rules of the Belgium FA.

Unsurprisingly, Bosman refused to sign and so was placed on the transfer list after which he negotiated a deal with USL Dunkerque. However, he was not allowed to move unless the French Second Division club paid a transfer fee. Liège demanded more than Dunkerque could pay, the deal fell through and Liège suspended Bosman, as the Belgium FA rules allowed them to do when they couldn’t reach a deal with an out-of-contract player.

Bosman summed up the absurdity of his situation in an interview with the Guardian years later, saying: “In other words, they thought that I had become four times better if I wanted to leave and four times worse if I wanted to sign again for them.” Working with lawyers Luc Misson and Jean-Louis Dupont, Bosman launched legal action against the Belgian FA, Liège and UEFA in the European Court of Justice (ECJ), citing the right to freedom of movement for EU citizens under the 1957 Treaty of Rome.

A confrontation between football authorities and the EU was on the cards even without the involvement of Bosman. UEFA, football’s European governing body, and the EU had been at loggerheads over the transfer fee system and quotas imposed on foreign players since the 1970s.

At the time, UEFA ruled that teams could only field three foreign players in European competition, plus two ‘assimilated’ players who had come through the youth team. In 1994 they determined that Welsh and Scottish players counted as foreigners in English teams, a restriction that meant Manchester United manager Sir Alex Ferguson was infamously forced to replace the Dane Peter Schmeichel in goal with Gary Walsh, against Barcelona, a game his side lost 4-0.

Both UEFA and world governing body, FIFA, are based in Switzerland, a non-EU country and at the time they believed this put them beyond EU law, an attitude succinctly summed up in 1988 by UEFA president Jacques Georges, who said: “[UEFA] can make up whatever rules we want, as long as they are within Swiss laws, as we have nothing to do with the [EC]”. He would soon be disabused of that notion.

Bosman’s case took five years to make its way through the courts but on December 15, 1995 the ECJ adjudged that the provisions of the Treaty of Rome were applicable to the practices of an organisation based in a non-EU country if they affected competition or freedom of movement in EU countries. Thus, the court ruled in Bosman’s favour, precluding clubs from demanding a fee for out of contract players moving between EU clubs. They also barred the restriction on number of EU players each club was allowed to field.

The impact of the ruling was huge. “All hell broke loose,” said Ferguson, later. “Suddenly it was a free-for-all.” Players exploited their new-found freedom by running down their contracts, leaving for nothing and negotiating bumper contracts with new clubs, which didn’t have to pay a transfer fee.

In a sport which has in the 25 years since the Bosman ruling also become proficient at maximising its income through increasingly lucrative TV deals, top players’ salaries rocketed by around 1,500%. So called super agents, such as Jorge Mendes and Pini Zahavi, became part of the football landscape. These middlemen capitalised on their position working for clubs and players to earn huge commissions, estimated to collectively total around £500 million in 2019.

Many clubs benefitted too. The ‘Gary Walsh Rule’ no longer restricted selection and in 1999 Manchester United won the Champions League final, with four EU players plus Dwight Yorke in the starting XI. Norwegian Ole Gunnar Solskjær came off the bench to score the winner. Four years later United signed 18-year-old Cristiano Ronaldo in a deal that would not have been possible without the Bosman Ruling.

Others were not so lucky. Ajax won the Champions League in 1995, beating AC Milan 1-0 in the last pre-Bosman final. The nine Dutch players in Ajax’s starting XI included seven players who had graduated from the club’s youth academy.

The Dutch club’s young, homegrown team reached the final again a year later, losing to Juventus. In the summer Edgar Davids and Michael Reiziger both left for free under the Bosman ruling and the team broke apart. Only three clubs from outside Europe’s top four leading leagues – Italy, Germany, Spain and England – have reached the final since then, with only one of them winning: Jose Mourinho’s Porto in 2004.

English clubs asserted their dominance in 2019 when they claimed all four spots in the finals of Europe’s two club competitions. Liverpool beat Spurs in the Champions League, while Chelsea beat Arsenal in the Europa League. However, the success was only nominally English. Just eight of the 44 players who started those games were home grown. The overwhelming majority were EU nationals or held EU citizenship.

However, it seems the Premier League will no longer be able to rely so heavily on the talents of EU players. Earlier this month, the FA, along with the Premier League and Football League revealed the regulations that will come in to force at the end of the transition period on the first of January next year. When it comes to the recruitment of overseas players, the new rules, agreed with the Home Office, will in effect act like a ‘reverse Bosman’ in several respects.

English clubs will no longer be able to freely sign players from the EU (and the European Economic Area, which includes Norway, Iceland and Switzerland). Instead, those players will have to qualify through a points-based system.

This will take into account factors such as the number of times they have played for their country at youth and senior level and how many minutes they have played for their club. Points will also be awarded on the basis of the quality of the club that the player is joining from, determined by the strength of league they play in, league position and success in Europe. Players who just miss out, can apply for exemptions.

Perhaps the biggest change is that clubs will no longer be able to sign players under the age of 18 from the EU, ruling out moves like the one which saw a 16-year-old Cesc Fàbregas move from Barcelona to Arsenal in 2003. Furthermore, in a bid to promote young British players, clubs will only be able to sign six overseas players under-21 per season.

It’s hard to know exactly what impact the new regulations will have but we can have some idea. A few years ago, Harvard scientist Laurie Shaw calculated that of the 1,022 EU players signed by Premier League clubs between 1992 and the end of the 2017/18 season only 431, or 42%, would have received a work permit if they had been subject to the same rules as non-EU players at the time.

The likes of Arsenal’s Héctor Bellerín, Virgil van Dijk, at Liverpool, and Chelsea’s N’Golo Kanté would not have been able to test their skills on a cold night at Stoke. Thus, the end to freedom of movement has the potential to see the international composition of Premier League squads revert to levels closer to those in the late 1990s, when the effects of the Bosman Ruling were beginning to take hold.

In the intervening decades, Bosman’s name has become part of football’s lexicon; useful shorthand for a particular kind of free transfer and thousands of players have become enriched thanks to his efforts. However, things did not turn out so well for Bosman himself. While his victory theoretically gave him the freedom to restart his playing career, his best years had been spent in a court room, not on the pitch.

During the five-year case he played only a handful of times for the French second division team Olympique Saint-Quentinois and CS Saint-Denis, on the tiny French island of Reunion, some 100 miles east of Madagascar. He eventually retired from the game soon after the verdict in 1996 after a spell with CS Vise, an amateur club in Belgium’s fourth division.

Bosman was awarded about £720,000 in compensation and in the immediate aftermath of the ruling, he sold his story for a documentary on Canal +. Much of the windfall was spent on legal fees, but he still had enough to buy a Porsche and a house with a swimming pool. Both have long been sold off as Bosman struggled to find work. Weighed down by debt and convinced that he had been ostracised from the game because of the stance he took, Bosman spiralled into depression and alcoholism.

He would later lament: “I did something no other player dared do. I ended a system of slavery. But it ruined my life.” Although Bosman won freedom for footballers, it seems he is still struggling to find freedom himself.

Five key Bosman transfers

Edgar Davids was the first major player to move under the Bosman ruling. After helping Ajax to a second successive Champions League final in 1996, the Dutch midfielder left for AC Milan, beginning the break-up of the team from Amsterdam. After a disappointing season he was sold to Juventus for £5.3 million, where he recaptured his aggressive form.

In 1999, Steve McManaman swapped Liverpool for Real Madrid. Anfield fans were disappointed not only that he left his home-town club, but also that they gained no transfer fee for him. Macca rubbed further salt in their wounds when he won two Champions Leagues, two La Liga titles, a European Super Cup and the Club World Cup with Los Galacticos at a time when the Reds were a fading force.

When Sol Campbell left Tottenham for Arsenal two years later in an even more controversial move, effigies were burnt in the street and the ex-Spurs skipper, who said he’d never play for their hated rivals, received death threats. None of this seemed to trouble Campbell who became one of the highest paid Premier League players, helped the Gunners win the Double in 2002 and was part of the unbeaten 2004 Invincibles team.

In January 2007 David Beckham announced that he would not be renewing his contract with Real Madrid. Instead, at the end of the season, he left to join MLS side LA Galaxy on a five-year deal worth around £138 million. Beckham helped the team win the MLS Cup in 2011 and 2012. He also helped raise the profile of the game in America, drawing in big name sponsors and opening the door for other major names to play in the US.

In 2012 French teenager Paul Pogba left Manchester United for Juventus on a free transfer after becoming frustrated at his lack of opportunities at Old Trafford. He won the UEFA Golden Boy award in his first season in Italy and was named in the Serie A team of the year for three consecutive seasons. By 2016 he was recognised as one of the best young players in the world and left Juve in a then-record £89 million deal to join… Manchester United.