Jamaica’s capital not only gave the world one of its greatest music stars, it produced a sound that has taken root around the globe. SOPHIA DEBOICK reports

Since the middle of the last century, music has gushed out of Kingston like a flood. The capital of a country smaller than Yorkshire, Kingston has a population that comes in at under a million, but it has been hugely musically prolific. The birthplace of ska, rocksteady, reggae, dub and dancehall, as well as a litany of legends, a seemingly never-ending panoply of inspired musicians and daring impresarios have made it in this city. Their stories are inextricable, as artists have emerged from tiny circles of influence in Kingston’s tight-knit neighbourhoods. A place with the highest number of recording studios per capita in the world, Kingston is the centre of the Caribbean music industry, but the international success of Jamaican music hasn’t meant a loss of its sense of its roots in the island’s history.

Jamaica is an island of myriad cultural influences. The native Arawaks were wiped out after the Spanish ‘discovery’ of the island, supplanted by African slaves as it became taken over by plantations. Slavery was abolished in Jamaica only in the 1830s, and African folk tradition runs ravine-deep in its culture, alongside the abiding influence of Christianity.

Rastafarianism emerged partly from the thought of Marcus Garvey – born in the north coast town of Saint Ann’s Bay in 1887 – becoming essential to Jamaica’s character, even if only a small percentage of the population espouse it. The music of the island, with Kingston as its heart, draws from all of these influences, from African drumming to Victorian hymns, resulting in sounds that are by turns rambunctiously witty or solemnly mystical.

Bob Marley’s fingerprints are all over Kingston. It all started in the ‘Government Yards’ model housing project of Trench Town in the south of the city. Neville ‘Bunny Wailer’ Livingston and Marley were both born in the village of Nine Mile, two hours’ drive north of the capital, but moved to Trench Town in the late 1950s, where the child born to Marley’s mother and Livingston’s father made the two brothers. In the early 1960s, they would meet a teenage Peter Tosh, who had moved to Trench Town from the far west of the island, and a trio formed that would go on to international fame.

But those times back in Trench Town would be immortalised in No Woman, No Cry (1975) (“I remember when we used to sit/ In the government yard in Trench Town/ Observing the hypocrites/ As they would mingle with the good people we meet”), while Trench Town Rock (1973) referenced Kingston 12, the area’s post code. Today, the tenement blocks are known as the Culture Yard, part tourist attraction, part community centre.

Indeed, Bob Marley and the Wailers are a huge tourist draw, with a whole suite of sites to be visited. Two miles away from the Government Yards, the headquarters of Marley’s Tuff Gong records remains one the major recording studios in the Caribbean, as well as a visitor attraction, allowing fans to see where Marley and the Wailers recorded their legendary songs.

The Peter Tosh Museum, established in central Kingston in 2016, displays personal memorabilia, including Tosh’s M16-shaped guitar and the unicycle which he often rode onstage, paying tribute to a man who was killed aged just 42 in a 1987 robbery at his home on Kingston’s Barbican Road.

More personal – and even spiritual for some – are Marley’s former homes. While Nine Mile boasts his mausoleum and the tiny house in which he was born, Kingston has the rather grander 19th century colonial house on uptown’s Hope Road that was Marley’s home from 1975 until his death.

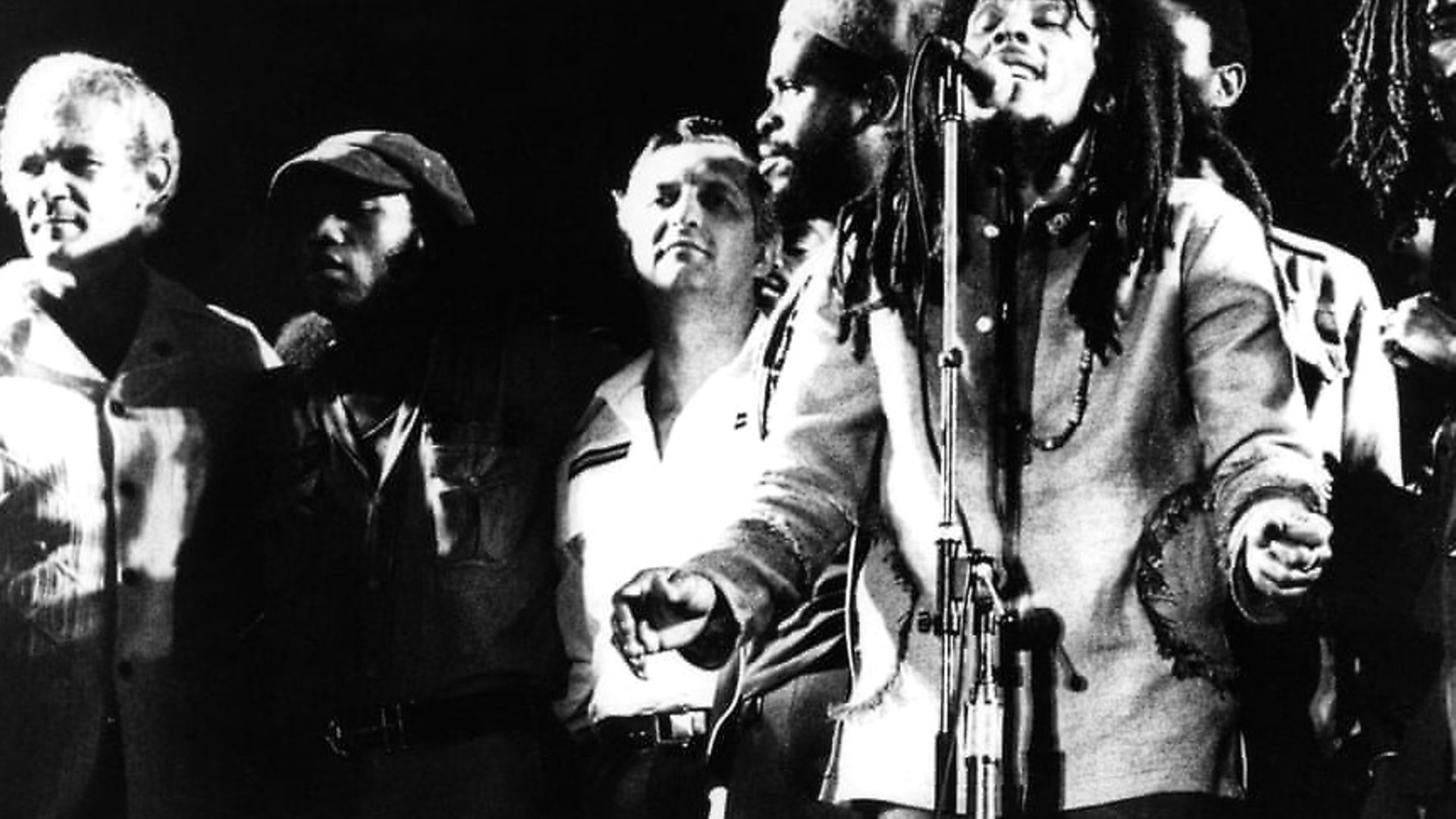

But the site that is most indicative of the deep significance of Marley and his music for the history of the island is the statue that honours him at the National Stadium. It stands as a reminder of both the 1978 One Love Peace Concert, which marked Marley’s return from self-imposed exile after his shooting in the midst of violence between the People’s National Party and the Jamaica Labour Party, and his 1981 funeral. In a gesture that came to be seen as highly significant, Marley became peacemaker at the concert as he joined the hands of the warring parties’ leaders on stage.

Such political relevance was part of the reason he received a full state funeral following his death from cancer at 36, the stadium being used in order to accommodate the sheer number of mourners. It was here that prime minister Edward Seaga delivered the eulogy amid a mixture of Anglican, Ethiopian Orthodox and Rastafarian rites. The coffin then made the long drive to Nine Mile for interment, and the man who many felt represented the soul of Jamaica became a part of its soil.

While reggae is Jamaica’s greatest musical export, its unmistakable easy, shuffling rhythm arose from a melting pot of earlier influences. The story of Jamaican popular music begins with mento – a folksy, acoustic style, sometimes described as Jamaica’s country music. When mento began to be commercialised in the 1950s it was often marketed as ‘calypso’ outside of the Caribbean, since the Trinidadian genre was already the focus of a burgeoning craze.

Harry Belafonte, an American of Jamaican descent, had success with Day-O (The Banana Boat Song) in 1956, which was the opener of his LP, Calypso, despite being based on a Jamaican traditional song. Kingston-born Lord Flea, sometimes referred to as ‘the Bob Marley of mento’ for singles like Naughty Little Flea/ Shake Shake Sonora (1957), cannily christened his band the Calypsonians and rode the wave of the calypso fad, even appearing in two Hollywood films, before his 1959 death in his mid-20s from Hodgkin’s Disease.

Lord Creator picked up where Lord Flea had left off. From Trinidad but making his career in Jamaica, he signified the shift to ska. His Independent Jamaica (1962), the first single on Island Records after it moved from Jamaica to the UK, was a calypso song which celebrated the independence referendum (“So the people voted wisely, now everyone is happy”), while King & Queen (Babylon) (1964) was a ska tune, released on Clancy Eccles’ Kingston-based label, and later reworked as the famous Kingston Town (1970).

Ska emerged from the west Kingston ghettos and was informed by the youthful confidence of the Jamaican independence movement, but its frenetic sound drew on a number of influences. There was the American rhythm and blues played by the sound systems, but there was also the native influence of Rastafari nyabinghi drumming.

Count Ossie first brought the nyabinghi drumming he had learnt in the Salt Lane west Kingston slum to Jamaican popular music via the Folkes Brothers’ Oh Carolina (1960), a single produced by the legendary Prince Buster (Buster was born right on Kingston’s music row, Orange Street).

Ossie also played with the original innovators of ska, The Skatalites, whose version of the Guns of Navarone was a UK Top 40 single in April 1967, many months after the conviction for murder of their leader, Kingston-born Don Drummond meant they had effectively disbanded.

Byron Lee and the Dragonaires, a function band who turned their hand to ska, recorded a song that claimed to sum up the genre, Jamaica Ska (1964), while Millie Small’s My Boy Lollipop of the same year was the result of Island shaping her into a star, and was rewarded with both a UK and US No.2 chart place.

Hyperactive ska quickly mellowed into reggae, but rocksteady formed the bridge between the two. More downbeat than ska and with less blaring brass, rocksteady came to international prominence with 007 (Shanty Town), a No.14 hit in the UK in the summer of 1967 for Kingstonian Desmond Dekker.

The Wailers went through ska and rocksteady periods before becoming the most famous reggae band in history, as did Toots and the Maytals before their 1968 single Do the Reggay became the first use of the term.

In returning to the indigenous aspects of mento and adding a strong political impetus from the pan-Africanism of Rastafarianism, reggae saw Kingston’s music reach its creative apotheosis. But it also became an international pop phenomenon in the 1970s, from Marley’s several Top 30 UK singles and mega-selling Legend compilation to Althea and Donna’s No.1 Uptown Top Ranking (1977), which took it all back to Kingston’s streets by referencing one of its swankier districts: “See mi in mi Benz and ting/ Drivin’ through Constant Spring.”

Kingston has continued to exert a powerful influence on music internationally in the last few decades in the form of dancehall and ragga.

Kingston-born Beenie Man, a presence on the UK chart since the mid-1990s, got his biggest hit, 2004’s No.7 Dude, in the same year that controversy exploded over his homophobic lyrics. In the 1990s the likes of Chaka Demus and Pliers and Shabba Ranks scored big hits.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Kingston’s Shaggy and Sean Paul put a dancehall sound firmly on the British and American charts. This is the Jamaican sound at its most brash, but the island’s music has had as many moods as its teeming capital does.