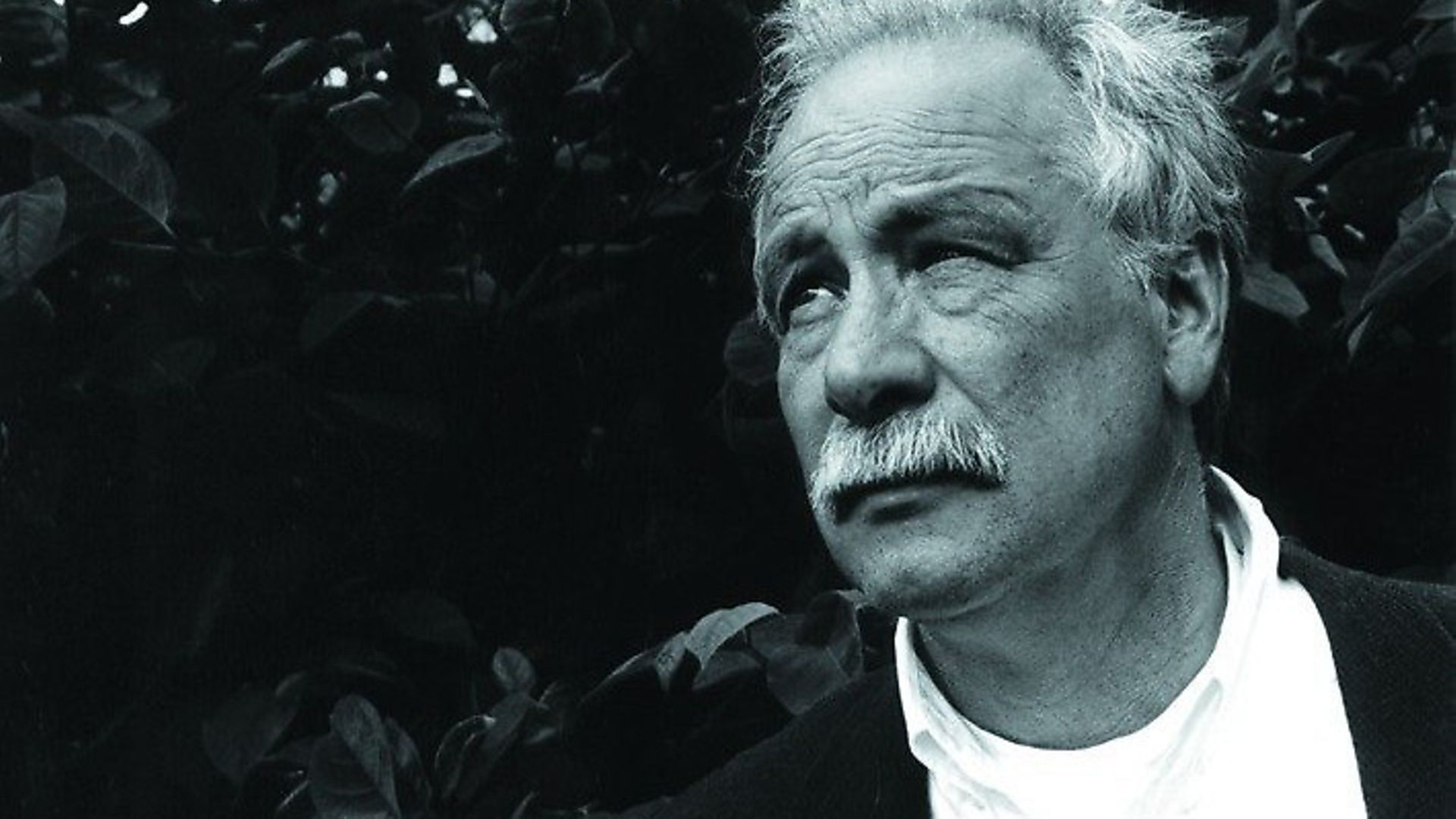

Max Sebald was a writer who never experienced the horrors of the 20th century but in his writings he could never escape them. CHARLIE CONNELLY reports on his life.

On June 8, 1944, a 24-year-old French resistance fighter was one of 99 men hanged by the SS at Tulle, south-central France, in response to a Resistance attack on German forces the previous day. Years later his daughter became friends with Winfried Georg Sebald, known as Max, for whom the massacre came to symbolise the frustration and injustice that thrummed through everything he wrote.

At the time of the incident Sebald was three weeks old, born in Bavaria while his father Georg was away in France serving in the Wehrmacht.

“My own father was stationed an hour’s drive from Tulle,” said Sebald during a 2001 interview. “I can’t get over the notion that I came from this year, 1944. I want to find out as much as I can about that time but I have a sense that as I pull out threads the entire fabric will come undone.

“I am following lines of pain. We are deeply disturbed as a nation. Collectively deranged. Who murdered my friend’s father in 1944?”

Three weeks after that interview Sebald himself was dead, killed in a car accident in Norfolk. That the Tulle massacre bracketed each end of his life, leaving three weeks either side, lent a dark symmetry to what was a lifelong attempt to deal with the collective silence of his compatriots in the aftermath of the Second World War. In doing so he produced some of the most innovative, adventurous, imaginative, addictive and quietly angry works of literature of a tumultuous century.

“There are many forms of writing; only in literature, however, can there be an attempt at restitution over and above the mere recital of facts, and over and above scholarship,” he said in a 2001 speech given in Stuttgart that proved to be his last public appearance.

He was 57 when he died and only just beginning to be recognised for his contribution to world literature. His novel Austerlitz had been published earlier that year, a behemoth of a book that told in a single paragraph the story of a boy growing up in a solidly chapel Welsh family who learns that he actually arrived in the country as one of the Jewish children evacuated as part of the Kindertransport. Added to his other acclaimed works The Emigrants, Vertigo and The Rings of Saturn, Austerlitz had transported the quietly-spoken German academic into contention for a Nobel Prize. Susan Sontag mourned a “contemporary master of the literature of lament and mental restlessness”, while Geoff Dyer marvelled at how, “Sebald’s hypnotic prose lulls you into tranced submission, a kind of stupor that is also a state of heightened attention”.

Sebald’s work could often seem contradictory, at once orthodox and experimental, allusive and literal, which may be explained by the combination of absence and presence that made his father’s role in his life so formative. Georg Sebald had joined the army in 1929 and remained in its service even as it became an instrument of the fascists during the 1930s. He was captured towards the end of the war and not released from a French prison camp until February 1947. By then the three-year-old Max had become used to a matriarchal home in a Bavarian mountain village where he doted on and was doted upon by his mother, elder sister Gertrud and his maternal grandmother. The only significant male presence in his early years was his kindly grandfather.

When Georg returned, naturally he expected to take his place as the head of the household. Physically weak and weighing barely eight stone on his return, he disrupted the peace of the house with a military-style authoritarianism and sense of discipline that traumatised his son. The most enduring legacy of his early years, however, would be what Sebald termed the conspiracy of silence that sought to omit the war and the regime that provoked it from the national discourse.

“I had heard practically nothing about the history that preceded 1945 until I was 16 or 17,” he said of his schooldays. “Only then were we confronted with a documentary film of the liberation of the Belsen camp. There it was, and we somehow had to get our minds around it – which of course we didn’t. It was in the afternoon and there was a football match afterwards.”

It was only years later when he found his father’s wartime photograph albums – all grinning group shots and off-duty horseplay – that Sebald realised he had taken part in the 1939 invasion of Poland. After his return Georg never mentioned his war service so Sebald was forced to resort to such ephemera in order to research the story. It was a methodology that shaped his writing career: His books all featured photographs scattered through the text.

Throughout his life he would be persistently reminded of the great national unspoken. As late as 1983, when he was long-established as a lecturer at the University of East Anglia, his mother sent him news that Armin Müller, a favourite teacher from his school days, had committed suicide. It was only by reading the newspaper clippings at the breakfast table of his home in Norfolk that Sebald discovered his teacher had suffered persecution at the hands of the Nazis for having a Jewish grandparent. Banned from teaching in the 1930s, he was still gentile enough to be drafted into the Wehrmacht on the outbreak of war.

It was this story that helped inspire his 1992 novel published in English in 1996 as The Emigrants, in which one of the four narrative threads follows Paul, a schoolteacher, a quarter Jewish, who serves in the army during the war and commits suicide exactly as Müller did.

Sebald had arrived in East Anglia via Switzerland. He’d studied German and English literature first at the University of Freiburg and then the University of Fribourg, a near-homophone that would have pleased him greatly. The move to Switzerland might not have been intended as emigration at the time but Sebald would never live in Germany again. In Fribourg he completed his master’s degree in just nine months, then married his Austrian wife Ute and spent a year as a schoolteacher in St Gallen before, in 1970, accepting a lectureship in Norwich.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that he began expressing his past, both personal and collective, in writing. The quartet of books that form the greater part of his legacy (there would also be collections of essays and poetry) inhabited a realm where fiction and non-fiction co-existed but sat comfortably in neither. The Rings of Saturn is arguably his best-known work and follows Sebald on a journey through Norfolk and Suffolk after a spell in hospital. While based broadly on true events there is much exaggeration and obfuscation, the odd quirk that was out of place, a road, even a station clock, that might prompt a reader’s letter of correction but was done intentionally in an act of truth subversion.

Places and events would trigger digressions into the past. In Southwold, for example, a television documentary about Joseph Conrad leads to an exploration of Belgian imperialism in the Congo and executed British establishment figure and Irish nationalist Roger Casement. Elsewhere, a ride on a miniature railway prompts musing on the Taiping rebellion and 19th century China while Diderot, Flaubert, Swinburne are part of a range of characters from history who walk through the narrative.

“If people were more preoccupied by the past maybe the events that overwhelm us would be fewer,” he said. “At least while you’re sitting still in your own room you don’t do anyone any harm.”

When he died he was driving into Norwich from the family home in the nearby village of Poringland when instead of following a left-hand bend his Peugeot went straight on and ploughed head-on into a tanker. An inquest established he’d suffered an aneurysm at the wheel that had most likely killed him before the crash: A witness in a car behind the tanker said that prior to the impact his head was back facing the ceiling and he was making no attempt to control the vehicle.

The loss to literature was palpable; there was much more to come. When asked if he believed he would ever work through his subject matter and come to a satisfactory conclusion he replied, “No, I shall never get out from under it. I can’t just forget about it. And what, go on a cruise?”