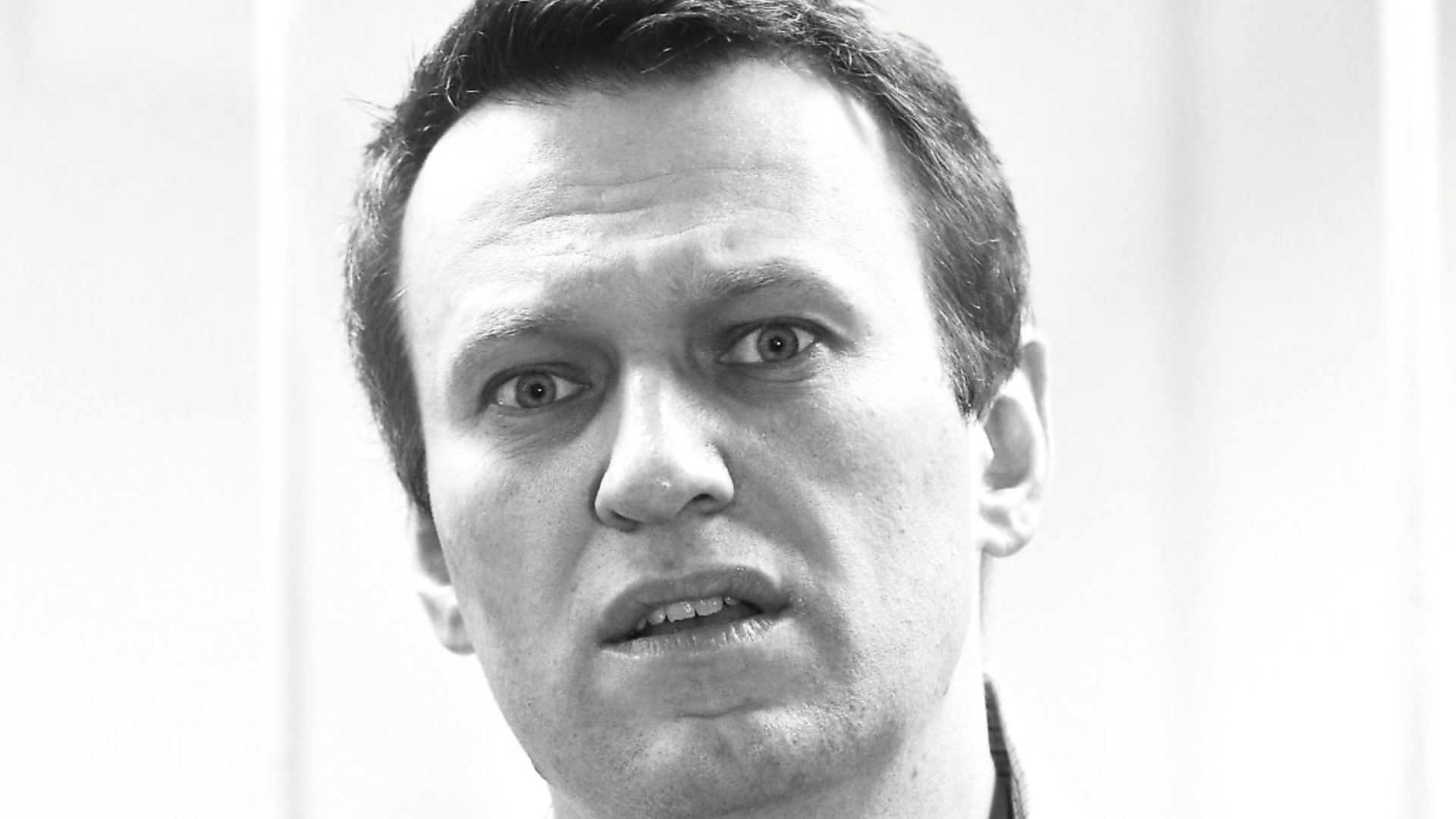

A profile of the Russian opposition leader who has taken on the perilous task of challenging Putin

Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny had only one complaint when he was sentenced recently to 30 days in jail for protesting against President Putin. ‘As if robbing the country is not enough for them – now they’re making me miss the Depeche Mode gig in Moscow too!’

Some might suggest that proves every cloud has a silver lining. Most would recognise the gruff insouciance and sense of humour that make Navalny an appealing leader of Russia’s growing anti-Putin protest movement. In reality, for all the dark wit that Navalny and his fellow Russians specialise in, even a short spell in one of Putin’s prisons is no joke. Nor is being an opposition activist. Incredible courage in the face of perpetual harassment is essential for opponents of the Putin regime. Numerous opponents of the Kremlin have been brutally assaulted, arrested or murdered, including former Prime Minister Boris Nemtsov, investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya and ex-security service officer Alexander Litvinenko.

Such oppression eliminated all opposition for several years. Even now, Navalny is the only active figure of significant stature and has already come under considerable pressure from the authorities. He was convicted in 2014 on dubious embezzlement charges. In a particularly nasty touch, his brother and co-defendant, Oleg, was sentenced to three and a half years in jail in an apparent attempt to press Alexei into ceasing his political activities. This April, Navalny was attacked for the second time with a chemical dye and had to undergo an operation to save his sight in one eye.

Whilst Navalny is undoubtedly brave, his rise to prominence owes as much to his outstanding communication and investigative skills. Navalny is a gifted orator who relates to people as an ordinary man campaigning for a better future for his country. He has a remarkable knack for distilling ideas into snappy slogans. His characterisation of Putin’s puppet ‘United Russia’ party as the ‘Party of Crooks & Thieves’ scans memorably in Russian and has stuck to it like chewing gum in a child’s hair.

Navalny entered opposition politics as an anti-corruption activist. That issue is still at the core of his campaign. His greatest talent is producing painstakingly investigated and smartly articulated exposés of the corrupt elite. His Anti-Corruption Foundation’s videos explain deliberately opaque schemes with a clarity that can be grasped by everyone. These films have become viral sensations in Russia.

Navalny’s latest bold video targets Putin’s long-standing mini-me sidekick, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev. Don’t Call Him Dimon: The Secret Empire of Dmitry Medvedev is Navalny’s biggest success so far and has been viewed more than 22 million times online. The film reveals some of the absurd wealth amassed by Medvedev during his time in office.

For several years, Medvedev was seen as a gentle, reasonably well-intentioned, liberal counterweight to Putin – hence the affectionate, diminutive nickname ‘Dimon’. But a series of missteps since have made him one of the most despised men in Russia. One of Medvedev’s most notorious blunders was an arrogant on-screen dismissal of a desperate Crimean pensioner. The pensioner asked him about the government’s refusal to index their already meagre pensions against Russia’s high inflation rate. An irritated Medvedev sarcastically told her ‘there is no money’.

Fatally for Medvedev’s reputation, Navalny’s video shows where the money for liveable pensions may have gone. It details the palaces, vineyards and yachts Medvedev has managed to acquire. More comically, it even notes the expensive trainer collection Medvedev has assembled, like a fitness freak version of Imelda Marcos. The value of these assets appear far beyond the reach of his official salary.

By implying the apparent corruption of the eternal Robin to Putin’s Batman, Navalny has struck closer to the President than ever before. This exposure further undermines the unlikely story some Russians still believe: that Putin somehow presides over this colossally corrupt system without being personally implicated in it.

The Medvedev revelations have added to the growing mood of dissent in Russia. This was already being fuelled by the fall in living standards. The country’s economic difficulties are primarily caused by mismanagement. But they have been exacerbated over recent years by the sanctions imposed on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine and the effect of the low global oil price on a country dependent on natural resource exports.

The cocktail of grievances also includes numerous localised issues. These range from the planned demolition of thousands of Soviet-era apartments in Moscow and the impact of new toll roads on hard-pressed truck drivers. The toll fees will go into the pocket of one of Putin’s closest billionaire cronies, Arkady Rotenberg.

All of these frustrations, have sparked street protests and a range of discontent that is unprecedented during Putin’s time in office. This is worrying for the Kremlin ahead of the 2018 presidential election. Whilst such elections are a stage-managed sham, the regime still prizes the limited legitimacy they convey. Putin correctly sees maintaining some measure of his popularity as essential to sustaining his authoritarian rule. He would prefer not to be seen as having to rig the vote too flagrantly.

Despite the growing discontent, Navalny is unlikely to obtain power any time soon. For now, his appeal is still largely concentrated amongst the younger, urban dwelling segments of society. Reaching beyond this relatively small, internet savvy group is very difficult. The Kremlin’s tight control of the traditional broadcast and print media most Russians still rely on gives it a formidable propaganda machine. The regime makes full use of its media dominance to alternately ignore and denigrate the opposition.

Even some of those protesting about one-off iniquitous acts by the government are hard for Navalny to reach. Given the chaos and widespread economic despair that followed the Soviet collapse in the 1990s, many Russians fear further dramatic change, despite their disillusionment. Focusing their frustrations instead on specific issues and individuals, like Medvedev and Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin, is based on the misguided myth that Putin is a ‘Good Tsar’ who can be prompted to pull his wayward underlings into line. This tendency was shown when some participants prevented Navalny from speaking at a Moscow apartment protest, despite his wife’s grandmother being one of the residents directly affected by the demolition plans.

To develop his leadership of the opposition further, Navalny needs to find a way to harness these disparate strands of dissatisfaction into a coherent movement. This will require him to do more work on presenting a programme that explains what he is for, in addition to the clarity some Russians already have on what he is against.

The most daunting challenge facing Navalny and the Russian opposition, though, remains the malevolent power of the Putin regime. It is deeply entrenched and contains many ruthless, illegitimately wealthy people who stand to lose everything if it falls.

The power ministries such as the Federal Security Service (FSB, in its Russian acronym – the former KGB) and the armed forces also believe Putin’s aggressive actions abroad have restored Russia’s pride. And, like the mafia don he frequently resembles, Putin has ensured the top brass are sufficiently implicated in the corrupt system to have a stake in its survival.

For Navalny, the immediate objective is to secure a place on the presidential election ballot next year. This will be difficult because his criminal conviction was engineered by the authorities to provide a legal justification for preventing him from standing. Even if he overcomes this obstacle, Navalny has little chance of winning such a heavily rigged poll. But it would provide a huge platform to advance his argument that Russians can aspire to more than the cynicism and corruption of Putin.

Blocking Navalny’s participation presents the regime with a dilemma. Doing so would drain any lingering legitimacy from the election by denying already disaffected voters a choice. This is already a sensitive subject after the fiasco of the last election in 2012. That campaign saw Putin and Medvedev arrogantly arrange between themselves to swap their President and Prime Minister titles to satisfy the letter of the constitution. Such chicanery was taken as an insult too far by many Russians and sparked massive protests which badly spooked Putin until they were suppressed.

Developing his programme and drawing the disparate single-issue protest movements into an opposition front too big to be crushed will be a tough task for Navalny. It is also a perilous one for his personal safety. But, by challenging elite corruption and catalysing renewed protests, he has already achieved more than most observers thought possible. And, as Russia’s revolutionary history and recent world developments show, change can happen surprisingly quickly once momentum has been generated. Navalny might not make it to that Depeche Mode concert. But the other defiant comment he made on his way to jail could one day come true – ‘the time will come when we will put them on trial (but honestly)’.

Paul Knott is a writer on international politics. He spent 20 years as a British diplomat, with postings to Romania, Dubai, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, Russia and the European Union in Brussels