In an epic and excoriating essay, editor-at-large ALASTAIR CAMPBELL chronicles the events and decisions of four traumatic months in UK history.

I am starting to write this at the end of a warm, sunny Good Friday, April 10, 2020. But I am in a burning rage… and it is health secretary Matt Hancock who has caused it. I can’t believe he said what he just said.

A few hours before his briefing of the media, increasingly frustrated at the journalists’ poor questioning at the daily briefings in Downing Street, I had posted a suggestion of 20 questions they should be asking of Hancock. One of them, Question 7 on my list, had just been asked.

It was from Charlotte Ivers of TalkRadio, by video link. ‘Can I ask how many front-line NHS workers have died from Covid-19, and has there been an investigatory process so lessons are learned and this doesn’t happen to their colleagues?’

Matt Hancock: ‘Yes, I think this is a question for you, Ruth.’

‘Ruth’ is Ruth May, the chief nurse for England.

‘F**k me, did he just say what I think he said?’ I said to an empty room.

Gasp. Rage. Still raging now, as I write this. Am I over-reacting? Am I being unfair, given just how hard the challenge that this crisis poses for a relatively inexperienced team of ministers, and a relatively inexperienced team in Number 10? But, seriously, did the health secretary just totally swerve a question about dead nurses and doctors? Did the chief nurse just say it would not be ‘appropriate’ to say how many had died, and who they were?

He did. She did. They f**king did.

They went into that briefing either not knowing how many people had died on what they keep calling the front line; or they did know but didn’t want to say, because it didn’t fit with the messages they had been told to get across, that they were ‘ramping up’ testing, and above all the über-message to the public to ‘stay home, protect the NHS, save lives’.

To be fair, after a very bad start on the comms front, when prime minister Boris Johnson was refusing to take the unfolding crisis seriously, they had got that message through, and most people were obeying it as best they could. ‘Stay home, protect the NHS, save lives’ – millions could recite it in their sleep by now.

However, when it came to a question about the lives, or rather the deaths, of the NHS staff making the ultimate sacrifice to save our lives, it was… ‘over to you Ruth’.

It was the moment when it became all too clear that something had gone badly wrong both with the government’s communication and the media handling of a developing national catastrophe. For if Hancock’s swerve was not bad enough, worse, the journalists asking the subsequent questions didn’t seem to notice. I am trying to imagine what the press pack of Good Friday 1998 would have done, amid the talks on the Northern Ireland peace deal that came good that day, if I, let alone a minister or the prime minister, had been asked a factual question about death rates of police, say, and not known the answer, or simply refused to answer it. They were a tough bunch. They would have taken me apart, and been right to. And that was in the New Labour honeymoon period. Fast forward to Good Friday 2003, a few weeks into the Iraq war, and I can barely imagine how the media would have reacted if anyone had shown such lack of empathy for our troops killed in action. ‘That’s one for you, general.’ I don’t think so.

I am pretty sure the public really do care how many nurses and doctors have died, and would expect the health secretary to know that figure, and to pay proper tribute to each and every one of them. But neither the government nor media are doing a very good job when it comes to telling the public what is happening, and why. This matters because this is a national catastrophe we are witnessing, yet neither politicians nor the media seems willing to see it, let alone admit it, and surely admission is the first step needed to reset and try to put things right, when so much has gone wrong.

THE CALIBRE OF GOVERNMENT

I’ve always sought to resist the ‘wouldn’t have happened in my day’ game so often played against me by Margaret Thatcher’s press secretary, Bernard Ingham. In this crisis, I’ve also tried to push aside the feelings I have long held that Boris Johnson, someone I have known since we were both young-ish journalists making our way, is not overly suitable for the role of prime minister. I’ve said more than enough elsewhere, pre-crisis, about his casual relationship with the truth, as a reporter in Brussels inventing all manner of nonsense about ‘Europe’ banning prawn cocktail crisps and insisting that men in possession of a great British penis were forced to use under-sized Italian condoms; or when campaigning in the EU referendum with his big promises for the NHS on his big red bus, or more recently with his ‘oven-ready deal’ to ‘get Brexit done’, when in truth he had barely peeled the potatoes. I’ve parked it all. He is the prime minister and, in a crisis as grave as this, the instinct should be to support, not tear down, the government.

That is the spirit in which I have said or written anything critical or questioning in recent weeks, fuelled by a genuine belief that tough but fair scrutiny of the government, by both opposition and media, should make for better government. I don’t like this line that I see developing in parts of the political and media landscape, that ministers should be given an easy time because this is so tough, and so many lives are at risk.

No. That breeds complacency. They should be treated with respect, because they have enormous responsibility; and with fairness too, because with that responsibility comes real pressure. But they should be challenged and questioned. It is not the challenging and the questioning per se that can help them do their jobs better; it is in their pre-empting the challenges and the questions, the work that goes ahead of the briefings, the substance of delivery, the amassing and assimilation of arguments, data and information, so it is all there at your fingertips when the questions are fired at you.

It is not just me, a fairly persistent critic of the government, who has been pointing out the deficiencies of government briefings. Former Tory minister and MP Nicholas Soames – grandson of Winston Churchill, no less – has become something of a minor Twitter star by ending his tweets with spectacularly long hashtags. He came up with a belter after education secretary Gavin Williamson’s debut Downing Street briefing on April 19.

‘Today’s ministerial briefing very close to a near death experience

#doitlessdoitbetterandusebigcompetentknowledgeableMinistersonly’

Big, competent, knowledgeable ministers? The government is not exactly over-run with them, and one of the questions this whole crisis has begged is just how low the general standard of really senior ministers has fallen.

When Soames’s grandfather was leading the War Cabinet, he had colleagues with serious organisational skills: Ernest Bevin was a hard-nosed, ball-busting, union organiser who, as minister of labour, made sure that democracy’s arsenal was built; Lord Beaverbrook was a hard-charging, wily operator on munitions; Woolton, as minister of reconstruction, always focused on winning the peace. And what do we have?

Gavin Williamson and Robert Jenrick, secretary of state for housing, communities and local government, who both looked like they were desperately auditioning for a prime speaking slot at the Tory Party conference. Priti Patel managed to invent a whole new maths system, when announcing the number of Covid tests that had been done – ‘three hundred thousand and thirty four nine hundred and seventy four thousand’ – and she was reading! On her next outing, she proudly set out how the government had presided over a fall in shoplifting. This, given most shops were closed, was hardly surprising.

First secretary Dominic Raab performed reasonably well, though with the rather odd habit of stopping half-way through sentences, as if suddenly asking himself how he became the de facto prime minister, and perhaps deep down knowing that many people watching were asking the exact same thing; Michael Gove was, as ever, fluent, grammatically flawless, but experience left you wondering what the hidden agenda might be. The day before Good Friday, it was business secretary Alok Sharma at the lectern, who not only doesn’t answer a question, but reframes it as a different question, and doesn’t answer that one either. It was as a result of his woeful performance, and the weak questioning by the media, that I wrote that blog with 20 suggested questions for the briefing on Good Friday.

‘Can I ask how many front-line NHS workers have died from Covid-19, and has there been an investigatory process so lessons are learned and this doesn’t happen to their colleagues?’

Matt Hancock: ‘Yes, I think this is a question for you, Ruth.’

Every time I think about it, my rage grows. Yet, the health secretary ducking a question about dead nurses and doctors did not make the TV news. It barely figured in the morning papers. Am I missing something here?

In normal times, as politicians obsess about who is up and who is down, and journalists make front-page news out of what in days gone by might have been a diary story, a lot of media output frankly does not matter. But in a crisis like this, it can be a matter of life and death.

Matt Hancock said as much a few days later, when refusing to be pushed on questions about an exit strategy from the lockdown, saying that if the government changed tack and its key message were diluted – stay home, protect the NHS, save lives – lives would be lost. ‘What ministers say, the words we use,’ he said in an interview, ‘are a matter of life and death.’

He is right. It is why it seems fair to ask, for example, whether, when we were being told all we really had to do to stay well was ‘wash your hands’, in fact this was not the case, and infection rates were soaring and the sickness was spreading as a result of the limitations of a policy that was reflected by those, presumably carefully chosen, words? When we were being told it was fine to go to the Cheltenham races, fine for Liverpool football supporters to go to a home game also attended by several thousand fans from already-partially-locked-down Madrid, fine for Rangers to play Leverkusen in Glasgow even after that, presumably it is fair, too, to look at whether those instructions led to people feeling more safe than they actually were, and see whether any died as a result?

Did the mixed messaging about who was or who was not a key worker mean that more people continued to work, and use public transport, for longer than they should have done? Did those crowded tube trains cause additional deaths of people who would otherwise still be with us? Did the fact of the prime minister saying it was fine to shake hands undermine his own government’s messaging on public health? In playing fast and loose with words, have they played fast and loose with people’s lives?

Now, as the focus of the crisis becomes our economy in the future as well our health today, chancellor Rishi Sunak can look back at a very positive press for his mid-March ‘whatever it takes’ Number 10 briefing. The securing of the headlines seems to have been easier than the delivery of his plans. The business loans scheme has shipped a tiny fraction of available money out of the door. Big business is getting more support than the small businesses which ministers are fond of calling the backbone of the economy. A return to work at 30% capacity is not viable for restaurants or office-based businesses that need to pay their rent; what’s the second wave of government support going to be? The policy matters most, but the communications matter too, and Sunak’s ‘whatever it takes’ may come back to haunt him.

It is easy to dismiss all communications as ‘spin’. But, in a crisis, communication really matters. It must be embedded in strategy. When making difficult decisions and presenting difficult choices, government must take the public into its confidence. That is Rule One in crisis communications. Other governments have done that. Ours, I would argue, has not.

If a situation is bad, it is best to say so. Say how bad. Try to explain why it is so bad and, more importantly, how you intend to fix it. Set out a plan. Do not, as Hancock and Ruth May did, go into a briefing without even knowing how many of the people working for you have died.

How to brief

For weeks, as the coronavirus swept across the world, I really tried to give the government, and the team in Number 10, the benefit of the doubt. I’ve known what it is like to be in there as the unexpected happens, and you’re bombarded with media and political attack, and the views of armchair experts 24/7 across the airwaves. We had some crises to deal with in our time – military, economic, health, terrorist, personal, political – but nothing like this, nothing so big, so multifaceted, so off-the-scale hard.

The economic impact is already bigger than the global financial crisis of 2008/9, and will frame much of our economics, our politics and social change for years. It is changing the way we work, communicate, travel, educate, treat illness, consume, relate to each other, and some of these changes will be enduring. The longer it takes to find a vaccine, the longer it will last as a major feature of our lives. The longer it lasts, the deeper the recession that will follow.

Also, think of the mental health consequences alone, for NHS and care workers dealing with this; families unable to say farewell, or console and bury loved ones; children unable to take exams for which they have worked, or de-socialised because of lack of contact outside the home; businessmen and women seeing their life’s work vanish; couples forced to confront their inability to spend time together; victims of domestic violence; the anger that is going to erupt if it becomes clear that thousands and thousands of deaths were the consequence of policy and capacity failures, as economic problems deepen… Without being too apocalyptic, it is possible that, however bad the crisis that the Covid earthquake has unleashed, the aftershocks will be even worse.

But first we have to get through the immediate crisis…

As the coronavirus rose up the news agenda, the focus was first Wuhan in China, then it spread further afield, notably to Iran, which felt suitably distant from the historically rich countries of the world, just as previous epidemics like SARS and Ebola had done. Then it struck hard in Italy, so much closer to home. I watched other governments doing what looked like the right thing, and ours doing what looked like the wrong thing, cocksure that such a thing could never happen here. They were Italy. We are Britain. Great Britain, like the prefix was a descriptive adjective awarded by the United Nations, not a historical and geographical accident.

As the temptation rose to say how badly I thought they were handling it, how ludicrously low-profile the prime minister seemed to be, how ridiculous it was that the Cobra crisis process had not been fully activated, to ask why we seemed to be taking a different approach from virtually every other major European power, I allowed these moments to pass, even as I noted the arrogance of some of the anonymous briefings coming out of Number 10, the suggestions that other governments were over-reacting, panicking; that ‘we knew best’.

So I sat it out, assuming that ministers and senior civil servants would be getting on top of things as the crisis came ever closer, dusting down pandemic emergency planning, and getting prepared. I took calls, and answered messages, from old friends in the civil service, who asked for my view of how to handle things. One said they wanted to draw on some of the ideas and structures we had developed during the crises of the Tony Blair years, notably Kosovo, 9/11, and the foot and mouth epidemic and fuel protests of 2000/2001. As things started to get more serious, one or two inquired whether, if asked, I would go back to help out. I said yes, of course, whilst knowing that Boris Johnson and the close knit group of Vote Leave advisers around him would never allow such a thing to happen.

By mid-March, I started to write down ideas, sometimes for private consumption by those who had asked for them, but then publicly too. I tried hard to be fair and constructive. Then, as now in writing this, I was not focusing on the science or the epidemiology, though I was reading widely on both. I was focusing, then as now, on strategy and communications.

On March 21, several weeks after Covid-19 had spread and risen to the top of the global agenda, eight days into my own self-isolation, with some countries already well into lockdown but ours still dithering, and the prime minister finally appearing at regular briefings to keep the public informed, I published 20 check-points for Johnson’s briefing team. My comments on how they fared against each suggestion, written some weeks later, are in brackets, in bold.

1. Start all briefings with factual updates. How many cases? How many deaths? How many full recoveries? Stats on NHS activity. Stats on Covid-19 tests. Stats on NHS staff tests, and sickness. Stats on ventilators. Stats on protective equipment. Stats on retired NHS staff returning. Explain any regional variations in cases and mortality that may be of interest/concern. Use visuals and graphics. Detail, detail, detail. (A few days later, they began to use some data, starting with public transport use, then known cases and deaths. But they consistently failed to provide data on key issues of capacity, instead offering new promises to replace previous ones which had not been met. For some time, they excluded care home deaths from the data, and when they began to include them, did so in a way that made it hard to assess a full total.)

2. Express sadness and regret at deaths, and thanks for all those in the public services and beyond who are helping. I can barely remember you talking about the dead and dying. Empathy matters, and make sure it is not formulaic. (Day after day, the same ‘our thoughts and prayers are with the families of those who died’ was trotted out. It seemed insincere. There was rarely if ever a tribute to, or the telling of the story of, real people, either those working on the front line, or those who had died. Boris Johnson showed real empathy for the NHS team that looked after him in hospital, but, in a lengthy speech on his return to Downing Street from convalescence on April 27, made no mention of NHS staff who had died, and no mention of social care home deaths at all.)

3. Have stories to tell of developments, and recovery, from the UK and elsewhere. (This has not happened. Instead, day after day, we got the exact same words at the start, then ministers telling us how hard they were working, with the cliché count off the scale. There was a lot of ‘tell not show’ rather than ‘show not tell’.)

4. Have a small team working round the clock on a global analysis of what is happening. Provide a short, distilled account of it. The good news and the bad. The trends, and good ideas, developing. The examples being set. Show the kind of thing that is informing your thinking and decision-making. (I don’t know if they had a team doing this, but if they did, there has been no evidence of its work at the briefings.)

5. Provide short, simple updates of everything happening across government as it relates to the virus. Pre-empt the difficult issues that are bound to arise, be that prisons, mental health, domestic violence, and so on, and set out the work being done, any changes being made, any messages you want to send. Do not shy from the complexity and the vastness of the possible ramifications. Do not pretend it is easy or straightforward. (It was some weeks before domestic violence was addressed, and I sensed that was because home secretary Priti Patel’s absence from the public arena had become an issue and so, on Easter Saturday, she was deployed to speak about this. But whereas I saw other governments address a whole range of issues beyond the immediate, ours has rarely done so.)

6. Explain how any progress made in the fight against the virus, or any setback encountered, relates to announcements made in the past, or being made now. Provide real, factual detail. Visuals, graphics. At each stage you have made changes, and said it was the right time to do so, you have not produced sufficient evidence as to why, or how the change relates to a broader plan. This erodes confidence. (They insisted repeatedly that they were following the science, and making the right decisions at the right time. But they did not share the science. As for making the right decisions at the right time, one day it would be the wrong thing to close schools, the next day the right thing, with very little explanation for the change.)

7. Consider doing the main briefing in the morning, and an online-only, shorter version later in the day. Allows you to control the agenda better, use the morning meeting processes to think through all difficult questions, use the afternoon to maintain momentum and prepare for the next day. There is no such thing as a media deadline in this. Set the rhythm of the day according to your needs, and the reality of the crisis, not the media’s. (This is more of a tactical than a strategic point. I can see why they stuck to the plan they had.)

8. Without being alarmist, be honest about how bad things are, and how bad they might get. (The tendency to gloss has consistently been stronger than the tendency to truth, throughout the crisis, including after Johnson’s return from illness.)

9. Do not make major change announcements without thinking through answers to every question likely to arise. It doesn’t matter if the answer is ‘we don’t know 100% at this stage’, but in some of the key changes announced, from school closures to pub closures, from help for business to help for workers, there have been too many unanswered questions, and too much confusion created by what you say. I am totally sympathetic to how hard this is, the pressures you are all under, the pace at which events are moving, but it has felt too fly by night. (On several occasions, including the one which sent me into a rage, I was shocked that they did not have answers to obvious questions. This has been a consistent pattern.)

10. Use visuals and graphics, and get them out on social media as you speak. You are getting large TV and radio audiences for the briefings, but most people will continue to absorb the news in bite-size chunks and online, after the event. You need to be providing them, verbal and visual. (I’m not aware if they did this, though they certainly had a highly active advertising campaign to promote basic messages about washing hands and staying at home. They finally used a graphic film – to illustrate the R-factor – many weeks later.)

11. Resist the snappy one-liners and the smart-arse language. I like to think I know my English, but I still had to look up ‘sedulously’ when you told the country that is the approach we should take. (Boris Johnson was taken ill not long after I wrote this, so on this, as on points 15, 16, 17 and 18, it is unfair to make too harsh a judgement as he did not do many more briefings before going into self-isolation and then hospital. As I say later, we did not exactly see a changed Johnson on his return, with his metaphors of muggers and Alpine tunnels, false claims about when we went into lockdown and, both outside Downing Street and at his first briefing after returning to work, claiming the government had presided over a ‘success’ – at a time we were passing Spain and Italy in the death stakes.)

12. Use powerful images already established in the media and public mind. I was surprised you did not speak out more strongly against panic buying. This may be your libertarian instincts. But your ‘I am sure everyone will be reasonable’ sounded ridiculous set against what we all knew to be happening – empty shelves, queues and fights in supermarkets, crowded pubs and clubs after you had suggested people didn’t go to them. How much better might it have been if you had played the clip of the Yorkshire nurse in tears because she could not buy the food she needed? To those who seem to think youth makes them invulnerable, play the clip of the Italian doctor talking about the people in their 20s and 30s, or the man in his 30s struggling to breathe as nurses in protective gear rushed around him. (They did not do this.)

13. Be ready to liven up the format. People will tire of the same format, and there is a risk they stop listening. Sad, but true. (They did not do this. Some weeks later they introduced the ability for a member of the public to ask a question. Good idea. On Johnson’s first briefing post illness, arguably the best question, on mental health, was from ‘Katie from Liverpool,’ and he frankly just waffled.)

14. Smarten up. Comb your hair before every briefing. This is not a trivial point. In times of crisis, people look to leaders for confidence and strength. If you look like a shambles, the fear people sense is that you are a shambles. (He did seem smarter for his subsequent TV address to the nation, and the later short videos he released.)

15. Stop charging into the briefings as though you are chasing down that boy you smashed on the rugby field in Japan. People want to see calmness. (He was a bit calmer post illness, but perhaps because he was worried about breathlessness.)

16. Stop hitting the lectern as you speak. It buggers up the sound. I know you want to communicate energy and drive, and that is fine. But wind down a couple of gears when you get into full flow. (He hit the lectern when answering questions which he was struggling with, and tried to replace fact with energy.)

17. No more homilies and rambles. Factual. Businesslike. When in doubt, shut up. (The mental health question, and another from the Stoke Sentinel, sent him into major waffle mode.)

18. Emphasise the long haul. Yes, people want hope, but saying you would deal with it in 12 weeks was a line not a plan. ‘Sending the virus packing’ was a line not a strategy. (Even as the chief medical officer, Chris Whitty, was standing alongside him, emphasising how far we were from the end of the crisis, Johnson, in tone and language, was trying to signal the opposite.)

19. End the silly boycott of certain news channels and programmes. It was childish at the time and it feels more childish now. (They did this, to some extent, but then picked a war with the Sunday Times, banning them from briefings, over a report the government did not like, and re-introduced a boycott of Good Morning Britain after Piers Morgan’s tearing apart of a succession of hapless and under-informed ministers.)

20. Broaden the team. You have to front most of this, but you also have to do a lot of work behind the scenes. Your ministers are also busy, but some more than others. Take three or four of the less busy ones, and turn them into all-purpose government communicators, a bit like you did with Rishi Sunak before the election. (They used a succession of ministers, but generally they stuck fairly closely to their own ministerial briefs. I had in mind here the way we used ministers like John Reid, Jack Cunningham and Margaret Beckett as ministers who, whatever their title, would be fielded as able and willing to speak across the whole of government.)

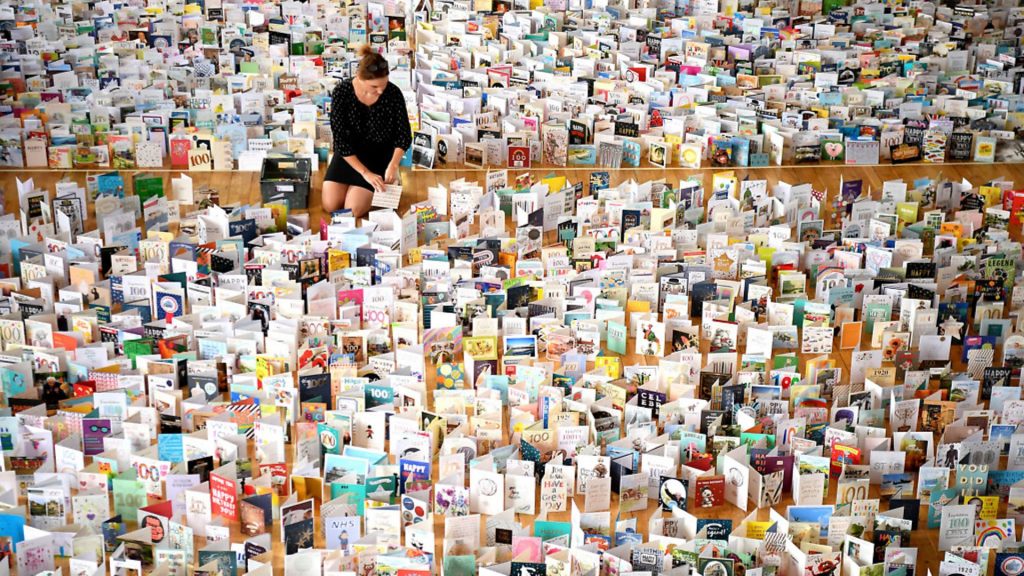

Looking back at that list now, I realise it is open to the criticism of being somewhat analogue in a digital age. To some extent, that is an inevitable consequence of people tuning in much more to traditional forms of media such as the BBC during times of crisis. Viewing figures for the main news bulletins have been high after steady decline caused by changed habits of media consumption. But the avalanche of shared videos and memes, as well as the sensational crowd-funding efforts for the NHS made by 100-year-old Captain Tom Moore, shows how much people were also communicating through social media.

On this, too, Downing Street was, at best, flat-footed and, at worst, negligent. On March 23, well over a month since the start of a public information campaign on the danger of Covid-19, Sky News published a report showing the government ‘had not run a single advert about the coronavirus pandemic’ on its official social media accounts.

That was despite the UK being offered millions of pounds worth of free advertising credits by Facebook and Instagram. Remember, this is a group of politicians and advisers whose supposed mastery of digital communications had won them the 2016 Brexit referendum and a general election four months previously. It is also the same government that spent £46 million on digital and physical adverts warning businesses and individuals to prepare themselves for a no-deal Brexit last year. The potential for benign targeting of different demographics – young people, the most vulnerable, NHS workers and those needing encouragement to seek medical attention for other conditions – was immense. But neither the government nor I, an analogue spin doctor, were thinking about this at the time the UK was probably at its most infectious.

None of us can prove whether the death rate, so appallingly high, would have been any lower if the communications had been better. It is interesting, however, that the two major democratic governments I would say have strategised and communicated worst – the US under Donald Trump and the UK under Johnson – have the highest death rates. On March 20, Johnson briefed the media, accompanied by chancellor Rishi Sunak, and Jenny Harries, deputy chief medical officer. They walked in together, inches apart. Their lecterns were not one metre apart, let alone the two metres recommended for social distancing. He set out the ‘clear message’ to the British people:

• ‘To stay at home for 7 days if you think you have the symptoms.’

• ‘For 14 days if anyone in your household has either of the symptoms – a new continuous cough or a high temperature.’

• ‘To avoid pubs, bars, clubs and restaurants.’ (Later he would order them to be closed.)

• ‘To work from home if at all possible.’

• ‘Keep washing your hands.’

There was still more talk of freedom than sanctions. Edi Rama, the Albanian prime minister with whom I have worked closely for some years, and with whom I was keeping in touch throughout the crisis, sent one of his ‘wtf!’ texts. It was not the first, or last, and he was not alone.

Friends in government in France, Germany, Norway and Australia were shocked that the UK continued to appear so cavalier.

‘Are these pictures on the Tube fake?’ asked a Singaporean civil servant meanwhile, as millions in the UK continued to use public transport. If you are wondering what the Singaporeans were doing on March 20, they were beginning to implement a measure announced two days earlier, making anyone who arrived from overseas, Singaporeans and foreigners alike, self-quarantine for 14 days. Failure to comply would result in a large fine or six-month imprisonment, or the revocation of residency and work passes. They were conducting swab tests of new arrivals, something that the UK was still not doing for vast numbers of visitors days and weeks later. They advised all Singaporeans to defer all overseas travel. They cancelled all ticketed cultural, sports and entertainment events at which more than 250 people were expected.

Singapore, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, countries across Africa too, were wondering what on earth the UK was doing. Still, the anonymous Number 10 briefers continued to tell the media that Britain knew best, the World Health Organisation was overreacting, the Europeans were panicking, we would not be hit like China, Iran, Italy…

A litany of errors

I have always defined a crisis in this way: ‘An event or situation that threatens to overwhelm and even destroy you or your organisation unless the right decisions are taken.’ It is as a result of that definition that I limit the number of full-blown crises experienced in a decade with Tony Blair to around five: foot and mouth; the fuel protests of around the same time, the turn of the century; the Kosovo conflict; September 11; and the wars which followed it, especially Iraq. The global financial crisis was after my time, but clearly fell into that category. There were dozens, hundreds even, of situations defined by the media as a crisis, but I make this point to emphasise that real, genuine, 24-carat crises are rare. They are rarer in developed economies than they are in the poorer parts of the world, not least because of infrastructure and government capacity. Complacency caused by a basic belief in your own systems, and a desire to believe optimistic rather than pessimistic forecasts, is not uncommon. Optimism is one of Johnson’s strengths. Here it became a fundamental weakness.

This complacency was a factor in most of the New Labour crises I mention above. During the conflict in Kosovo, we were far too slow to realise that Nato was as much a brand, and an administrative organisation, as a fighting machine in itself. Ultimately, the major governments had to step up not merely with the provision of military hardware and troops, but with the organisation necessary for the propaganda battles that for some time, whatever his military inferiority, Serb president Slobodan Milosevic was winning. It took a major overhaul of the communications, and of the systems of cooperation, before we could properly fight back. Militarily, it was like Barcelona against Hartlepool.

In the foot and mouth epidemic and the fuel protests, we were too slow to realise that these were both situations whose impact and consequences were going to be beyond one department. The Ministry of Agriculture wanted to be in control because it feared an undermining of its reputation if we took over. And in the fuel protests we had the opposite of the usual turf wars, when ministers and departments want to accrue power rather than give it away. The Treasury saw it as a policing issue or a transport issue, and those departments should be in the lead. The Home Office saw it more as an economic or a transport issue. The Department of Transport saw it as a Treasury or Home Office issue. Perhaps it is the nature of a crisis that there will be a few days when it seems nobody is in control. But in our system of government it must ultimately be the centre that takes it. We were too slow back then. This time, as an even bigger crisis developed, Downing Street was even slower.

As for Iraq, once the decision to take action to topple Saddam Hussein was taken, we were so focused on the military campaign that we made too many assumptions that the senior partner in the operation, the United States, would also be focusing properly on the aftermath. The military campaign was hugely successful, and though there was considerable opposition to the government approach, there was also a good deal of support. Indeed, the Tory charge was that we were too slow. But the real crisis for the UK government came afterwards, focused on failings of post-Saddam planning, and the failure to find weapons of mass destruction. Ironically, the famed WMD dossier was born of a desire for openness and transparency about the decision-making process; something I feel has been lacking in the Number 10 approach on Covid-19. Perhaps that explains it, I don’t know. But I do not believe modern crisis management can be successful without a commitment to openness and transparency. The Labour government chief scientific adviser during the foot and mouth epidemic, Sir David King, who has established ‘Independent Sage’ to shadow the official body advising the government, clearly thinks the necessary transparency is not there.

The second part of my definition – ‘unless the right decisions are taken’ – is every bit as important as the first. Just as Tony Blair, when fighting the election in 2001 on the prosaic slogan ‘Schools and Hospitals First’, did not expect his second term to be defined by September 11 and its consequences, so Boris Johnson did not imagine his ‘Get Brexit Done’ election would be followed so soon after by a pandemic. Part of crisis management is adapting quickly and effectively to new, unexpected realities.

Johnson had been very low profile on the floods, which now seemed so long ago, but which at the time were devastating for so many people. He was low profile on coronavirus, appeared reluctant to front the government response, and, when he did, it was in campaign mode – a photo-call at a rugby match, snappy one-liners, mixed messages galore.

Meanwhile, ‘herd immunity’, first briefed out of the side of special advisers’ mouths, became a slogan and then – or so it seemed when the chief scientific adviser Patrick Vallance seemed to confirm this in a BBC interview – a strategy. Of all the loose briefing and mixed messaging, the herd immunity period was surely the worst. When they should have been going early and going hard, they were playing fast and loose with one of Dominic Cummings’ pet theories, and one or two scientists, perhaps too drawn to the flame of power at the centre, went along with it.

There were so many mis-steps in those early days as the crisis grew, born I suspect of the failure of Johnson and his team to shift from campaign to government mode, and then from normal government mode to crisis mode. The prime minister, as per reporting in the Sunday Times, failed to attend a Cobra meeting until early March, missing no fewer than five of its meetings. Key people from outside the narrow tribe, such as London mayor Sadiq Khan and the first ministers of Scotland and Wales, were initially excluded when unity should have been a byword for the approach.

Through February and beyond, as I know from my conversations with some of them at the time, ministers and officials sensed Johnson was more focused on how to break the news of his partner’s pregnancy, and resolve issues with his family, than getting on top of the virus which posed a potential threat to every family in the country. They failed to order personal protective equipment when there was time, failed to order sufficient tests, refused to participate in daily EU health ministers’ crisis calls from which valuable lessons could have been learnt, or join a Europe-wide scheme to access vital equipment. Even by mid-March the government advice to care homes, their staff scandalously under-protected, was to say it was ‘very unlikely’ their residents would contract the disease.

They let major sporting and cultural events go ahead. They failed to institute checks or quarantine for arrivals from Covid hotspots. They claimed to have ‘scientific evidence’ to justify Britain flouting WHO advice to ‘test, test, test’. They claimed to have ‘scientific advice’ for every move they made, or didn’t make. They just didn’t publish it, or share it with the public. Secrecy seemed to trump transparency every time. Assertion trumped argument.

Questions as bad as the answers

A proper crisis communications strategy is one in which leaders take the public into their confidence about the process and the reasoning behind their thinking, and the decisions they make. They have to decide, execute but also narrate a strategy. Both as journalist and politician, Johnson has never been one for complexity. In common with most populists, he likes to pretend to people that life is not complicated; that everything can be summed up in a snappy phrase: take back control… get Brexit done… wash your hands… whatever it takes… send the virus packing….

The current crisis was always going to play out in all manner of unexpected ways, and Johnson should have been honest with the country about that. It was impossible to know with certainty how many would die, and whether the NHS would be able to cope. Only by being honest about the situation could he hope to secure public confidence and understanding for the decisions made to seek to improve it. His ‘we can send the virus packing in 12 weeks’ boast was foolhardy. Other acts of posturing, proudly talking of how he shook hands with people in a hospital treating coronavirus patients, now seem part of a quite disturbing pattern. By the time he shifted gear, with his statement that ‘I have to level with you, many more families are going to lose loved ones,’ it was too out of kilter with his previous statements, so it simply looked like a loss of control. The government has never fully regained it. See point 6 in my checklist above.

This foolhardy, cavalier, British exceptionalist pattern was clear as far back as early February, when he was seeking to portray himself as Superman, able to defeat the virus without the drastic measures others were then introducing. In a long speech, the sole reference to the coronavirus issue then soaring in importance and difficulty around the world, is worth quoting in full:

‘We are starting to hear some bizarre autarkic rhetoric, when barriers are going up, and when there is a risk that new diseases such as coronavirus will trigger a panic and a desire for market segregation that go beyond what is medically rational to the point of doing real and unnecessary economic damage, then at that moment humanity needs some government somewhere that is willing at least to make the case powerfully for freedom of exchange, some country ready to take off its Clark Kent spectacles and leap into the phone booth and emerge with its cloak flowing as the supercharged champion, of the right of the populations of the earth to buy and sell freely among each other.

And here in Greenwich in the first week of February 2020, I can tell you in all humility that the UK is ready for that role.’

I look forward to that one being played at the public inquiry, and in courtrooms.

It was after the Alok Sharma briefing on April 9 that I realised the questions were as much a part of the problem as the answers. The format, with the reporters called from a prepared list by ministers, and then brought in by video-link, favoured the government, especially as, initially, they did not allow follow-up questions.

Having done many hundreds of briefings on behalf of the government, I know that the toughest questions are the short ones, with a factual answer, and where it is reasonable to expect the person being asked to know it. The easiest questions are those which present an opportunity simply to repeat what you have already said.

Asking a minister a question about how they feel – ‘Are you worried that?’ – or asking them to speculate – ‘Do you think it will get better or worse?’ – or giving them a multiple choice – ‘And finally, minister, if I may…’ — are, in general, wasted questions.

The other situation that puts the briefer under legitimate pressure is one where the media work together. I knew from my time as a reporter that sometimes working as a pack was the only way to elicit information that, for whatever reason, the government did not want to give. And I knew from my time as a government spokesman that, when a pack is in legitimate full cry, you have to provide real answers. So when journalists were being limited to one question, they should have worked together if any question was not being answered. They played into the government’s hands and possibly overlooked the fact that these briefings, especially as parliament was not sitting, were for the public as a whole.

Facts, please, not platitudes

‘How many frontline NHS workers have died?’

‘Yes, I think this is a question for you Ruth.’

What happened to leadership? Transparency? Empathy? What happened to communications embedded in strategy?

Ruth May’s answer merely compounded the rage.

She looked momentarily uncomfortable and would have been perfectly within her rights to say: ‘No, secretary of state, it is a question for you.’ Instead, she gave every impression of just having graduated from the Tory Party school of spin by platitude – ‘we know every death through coronavirus is a tragedy… heart-breaking…’ before getting to what I assumed would be a factual answer:

‘We do have numbers of people that have died, whether nurses, midwives, healthcare workers, doctors. It would be inappropriate for me right now to go into listing or numbering them…’

Hold on, she didn’t ask for names. Why can’t you say how many?

‘…because we haven’t necessarily got all of the permissions of all of the families across England…’

They just want the number. Please, tell us the number.

‘…but I recognise that we will want to make sure that we are learning any lessons that should be learned, but it would be inappropriate for me to comment on any individual death…’

Please, just answer the question.

‘…whether that is one of our health care workers, or not…’

She didn’t answer the question.

Finally Matt Hancock spoke: ‘Thanks very much, Charlotte. Now, the next question is from…’

The TalkRadio political reporter was muted. No follow-up for her. And not one of the other journalists called went back to the question. Not one.

My God, what would the Good Friday press pack of 1998, or 2003, have done with that? I’m not sure Matt Hancock would have got out alive. ‘What do you mean, you can’t say how many dead? What the hell are you talking about?’ Similarly, when Hancock made an Oscar acceptance-style speech as he claimed to have met the target of carrying out tests on 100,000 people daily by the end of April, he and his supporters went into full peevish mode when some in the media pointed out that the figure included tens of thousands sent out rather than carried out, and that some were double-counted. The 1998 pack would have torn his claims apart, rightly.

It seems the ‘feral beast’ of which Tony Blair spoke when he made a speech about the media, towards the end of his time in office, has been largely tamed, voluntarily. As journalist Steve Richards tweeted: ‘If this had happened in the New Labour era, all hell would have broken loose… calls for A Campbell to resign, a thousand two ways on TV and radio on ‘spin’, articles and specials on ‘spin’, calls for Blair to ‘apologise’ and publish the true numbers tested.’

Is this just the press representing a people who want the government to do well in a crisis? Do I want a return of the feral beast approach for the pandemic, when the only story that counts is one that is bad for the government? No, certainly not. I am simply making the point that it is not always the case that the media becomes easier to handle in a crisis. Indeed, often we discovered it to be the opposite. Foot and mouth, fuel protests, definitely. Iraq, for sure.

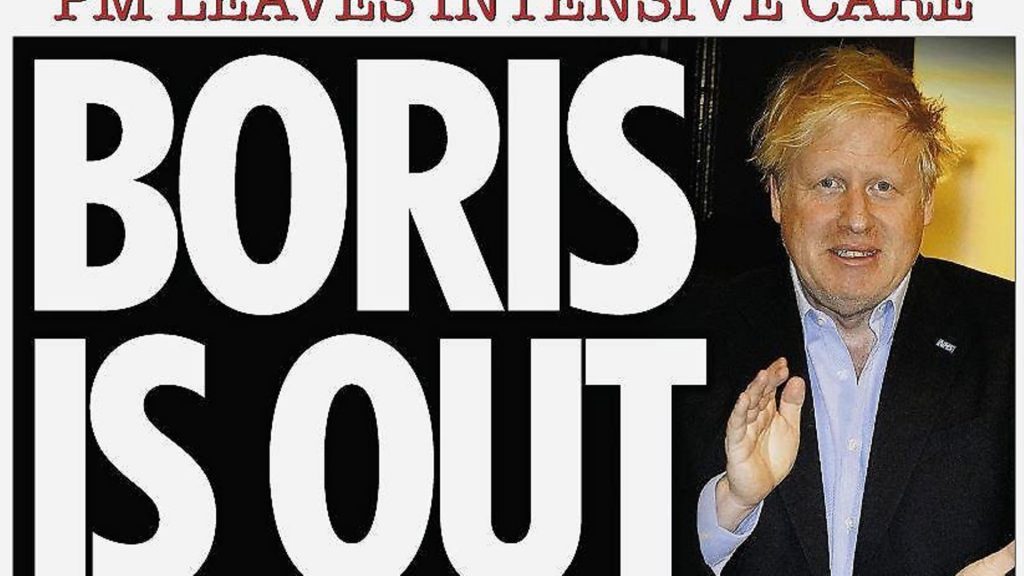

Yet I can look at the Sun in particular, on the day the UK death toll was surpassing Spain and Italy, and I see on their front page: ‘Now that’s a Good Friday’. Why? Because the welcome news that he had been moved out of intensive care was deemed to be more important than 881 people dying on the same day, and thousands of families grieving as the death toll kept rising. We were instead being invited to rejoice at the recovery of one man, whose decisions in the early days of the crisis and since almost certainly contributed to those deaths.

The stories, the lives indeed, of the thousands of dead, the hundreds of thousands of grieving, were buried, lost in the repeated updates of the prime minister’s ‘high spirits’ from his bedside spin doctors.

Yet nurses and doctors were dying now, and their stories were barely being told, as occasional briefings about puzzles Johnson was doing, or the films he was watching, soared to the top of the news agenda. I saw a tweet from a Canadian, who said he picked up the Canadian press and read terrible stories of the rising death toll in the UK and the appalling working conditions of NHS doctors, and then looked at British papers telling us how good Boris Johnson was at sudoku. These same papers had been reporting with greater urgency and drama lower death rates in Italy and Spain than those now happening in our midst. When those countries reached their daily peaks, 971 and 950, we stared in disbelief at medics in hazmat suits, overcrowded hospital wards and ice rinks turned into morgues. But now we were in the same place, stories of how Carrie Symonds cheered Johnson up with pictures of their baby scan took precedence.

The forgotten

It is one of the great ironies of the modern age that there is more media space than ever before, yet so little diversity in what TV, radio and newspapers deem ‘a story’ to be. To follow most of the UK media after he was taken to intensive care, there was only one ‘story’, and that was Boris Johnson and his health.

In criticising the media’s approach, I do not minimise either the significance of a prime minister being in intensive care, or the widespread sympathy and concern it aroused. However, the focus on his situation became disproportionate, and risked becoming a distraction from what both government and media should have been focusing upon. Can anyone recall the name of the consultant geriatrician whose death in Kingston hospital was announced at the same time as Johnson entered his second night in intensive care? Dr Anton Sebastianpillai. He was in his 70s, his sad death barely noticed amid the non-stop chatter about Johnson. Could we recall how many deaths there had been the day before, here and in other countries around the world? Did we recall any update on the situation regarding testing, ventilators or protective equipment for NHS and social care workers? These were huge issues before Johnson went into hospital, they remained huge issues afterwards, and genuine public interest was not well served by losing sight of that.

I understood why the government, and parts of the media, wanted to continue to present Johnson as a strong figure, because leadership matters in a crisis. But once he was in intensive care, his life in the hands of real doctors not spin doctors, they should have dialled down on the ‘he’s a fighter’ rhetoric. What does it say about people who have lost that fight against the same disease – that they weren’t fighters, because they died? Words matter always. They matter a lot when people are grieving. Those words risked being hurtful to so many, but ‘the story’ of the hero leader fighting to get back on the battlefield was too tempting for his media fans.

On that day when Matt Hancock wouldn’t tell us how many nurses and doctors had died, he was so happy to tell us Boris Johnson was sitting up, and so, so grateful to the nurses and doctors who were looking after him. When Johnson was out of hospital, pretty much the whole country, and much of the world, got to know Jenny from New Zealand and Luis from Portugal, the two nurses who had watched over him in intensive care. Could anyone name the nurses and doctors who had died? Hancock didn’t know how many, let alone know all their names, and the criticism of this stunning lack of empathy in the pro-Johnson papers – zero.

The Sun, for example, led its coverage on Johnson’s health, as the death toll mounted around the country, every day he was in hospital. We have seen similar dedication to Johnson the person, rather than Johnson the leader, since the birth of his son. Years of waving away questions about his private and family life on the grounds that ‘I never talk about that,’ have given way to considerable talking about it. It is hard to escape the suspicion that this helps the prime minster and his many media fans to focus less on just how much has gone wrong as a result of his decisions not as a father but as a politician.

There is no doubt that several of the newspapers now are making little attempt any more to separate news from comment, fact from opinion. It is a hugely important part of the populists’ armoury, backed by the exploitation of overtly opinionated radio presenters and social media armies. And though newspapers have always been, to greater or lesser degrees, subject to the political influence of owners, that has grown even since my time in newspapers.

Technology which has, on the one hand, been a liberation for the media has also played a role in thinning out journalism. When I was a journalist, and for much of the time I was in Downing Street, reporters on the dailies could wait till around 5pm to file their copy. Broadcasters might do three packages each day on a busy story. Today they are at it all day, TV, radio, online, blog, tweet, Facebook, Instagram, they don’t have that much time for what you might call journalism. Broadcasters’ questions at briefings are as much about getting into their own packages as eliciting information.

Who does it well?

It was on March 13, returning by train from taking part in BBC Sport Relief in Manchester, that I decided, well ahead of government advice, to self-isolate. I have a history of asthma, and two brothers who both died aged 62 (my age!) in part because of respiratory issues. I had also been reading an awful lot about coronavirus, and talking to politicians and experts in those parts of the world where I do strategic advice. In particular, Edi Rama was sending me some of the scientific papers on which the Albanian government was basing his government’s decision to go for an early lockdown. Senior people in France were likewise sending me similar papers and articles, but usually accompanied by an exasperated question, roughly translated as: ‘what on earth is Boris Johnson doing?’

We were not even half-way through March, when Albania was in total lockdown, including strictly enforced curfews from 1pm to 5am, with only one person per family member allowed out to go shopping, monitored by online tracking. Rama was now sending me photos of empty streets along with the vast volume of scientific papers he was hoovering up. He was also sharing in the French exasperation at the UK approach, for example sending a BBC headline on Boris Johnson saying schools would stay open because ‘closing then could do more harm than good’ with the message ‘WTF!! God help you if this is his ‘scientific advice’ … Italy was ruined by this approach’.

He sent me a photo taken on a bus, on which a police officer, like the driver wearing a mask, ensured only healthcare workers got on. Alongside it, a picture he had seen of a packed train platform in London. ‘Do they know what they are doing?’ he asked. ‘You are heading for catastrophe.’

Two short weeks later, the situation in Albania was sufficiently under control (at the time of writing, 416 cases, 23 deaths) for Rama to be able to send doctors to Italy where, in a recent poll, he came top in an analysis of world leaders and how they had handled the crisis. He subsequently offered healthcare professionals to the UK, but was told everything was under control, but thanks for the offer.

After a while, I had to give up watching Trump. The lies, the racism about the ‘Chinese virus’, the mixed messages and incoherent rambling, the turning of people in Democratic states against their governors. Disgusting. By the time his 90 minute rambles included the suggestion that doctors might look at injecting disinfectant, even the memes about him stopped being funny. But I continued to watch New York governor Andrew Cuomo’s briefings. Whereas Trump’s were a mess, Cuomo’s were a masterclass in crisis comms.

Have your say

Send your letters for publication to The New European by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk and pick up an edition each Thursday for more comment and analysis. Find your nearest stockist here or subscribe to a print or digital edition for just £13. You can also join our readers' Facebook group to keep the discussion and debate going with thousands of fellow pro-Europeans.

Cuomo’s father Mario served three terms as New York governor, and was the author of one of the most famous quotes about politics ever made: ‘We campaign in poetry, but we govern in prose.’

His son’s briefings are the very best in prose.

Cuomo was effective at comms once the crisis took hold. Others were effective at crisis management and comms before it did so. New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern’s ‘we go early, we go hard’ was a superb strategic message. Her line that ‘we only have 102 cases, but so did Italy once’ is perhaps my stand-out line of the entire crisis. Only 19 New Zealanders have died.

Greek prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis has done his country’s battered standing no harm with his superb handling and comms. Irish Taoiseach Leo Varadkar’s return to work as a doctor was as good an example of ‘leading by example’ as you could hope for. And though China is taking a lot of political heat over the virus being unleashed on the world, the smaller countries in that part of the world have managed the crisis well.

To have a sense of the difference in approach from the UK, consider what Anthony Costello, professor of global health at University College London, and a former director of the World Health Organisation, told me: ‘South Korea saw their first ten deaths on Feb 25. They started mass testing on Feb 22, three days earlier, and effectively suppressed the epidemic within 17 days. They had partial lockdowns in hotspots but no national lockdown. A month later, their growth rate was still 1% and the president won a landslide election. And they have a method in place to pick up a handful of cases every day.

‘The UK saw our first 10 deaths on March 13. The day before we had stopped all testing and contact tracing in the community, gone for herd immunity to get 60% of us infected, and the government reassured us there might only be 400,000 dead.’

Lasting damage

Let’s think back a little, just a few short weeks, when we stared at our TV screens, or looked at those shots of page upon page of death notices in the local papers in Lombardy or Valencia, and we went ‘poor Italy, poor Spain’, and somehow assumed, encouraged by government to do so, that it could not happen here.

The simple truth about the UK is this: we did not act early, we first chose a different strategy, herd immunity, then tacked to another one, mitigation, and then eventually a form of lockdown. But, overall, the strategy has failed, massively. By going too late into lockdown, we will almost certainly be late to fully emerge. By thinking energy and optimism and Britishness were sufficient weapons to fight the virus, we have ended up being one of its most prize victims.

I think back to those ‘wtf’ texts from Edi Rama, his obsessive tracking of our media headlines, and his little comments: ‘this is bulls**t… not true… crazy… this is f**king madness… look at this (another scientific paper, or another shocking report from around the world)… Italy did this, why is he doing this?… is there nothing you can do?’

And no, basically, there wasn’t. All I can really do is write, tweet, talk, cajole, try to influence opinion inside and outside the government. But compared with the power of ministers, senior advisers, scientists with the ear of both, or editors of TV bulletins and national newspapers, it is pissing in the wind. Real power is in government, as it should be, because that is where the people have put it. But when the government is failing, but not held to account by a media that has lost its way, the damage to the body politic is real and lasting.

It suited the agenda of the Tories and the media, at the time we were in power, to present ‘spin’ as some kind of New Labour invention, when, in truth, effective communication has been a part of effective public leadership since the Bible, or since Julius Caesar said after the brief and brutal Battle of Zela ‘veni, vidi, vici’. To this day, in my view, the greatest soundbite ever delivered. 47BC. Quite a while before my time.

‘Spin’ became a catch all term of abuse for anything which anyone said, and Boris Johnson, in his work with the Spectator magazine and the Daily Telegraph and elsewhere, was as fond as anyone of suggesting there was no objective truth being presented, just a government of liars seeking to manipulate the media to portray us in a positive light. This was happening long before the Iraq war, I might add.

I look at the current government, and the current media, and I might be willing to take some of the criticisms thrown our way when we were in power. Yes, I was a control freak. Yes, we wanted to set the agenda, but that was because if you don’t, and you allow others to, you have less chance of delivering on the changes you want to make to the country. But I think the constant charge of government by spin, with media as willing co-spinner, applies far more to the landscape today than it did back then.

As April neared its end, and Jacinda Ardern announced that New Zealand was the first country in the world to defeat the virus, and began to emerge from lockdown, the news was rather gloomier in the UK.

On the same day, British Airways announced 12,000 job losses, a sign of further economic disaster ahead. New figures showed the full extent of the death toll in care homes, which took the UK to the highest in Europe. The day before, I had pointed out that the total of recorded deaths in hospitals alone, at just over 20,000, now matched the capacity of Turf Moor, Burnley FC’s stadium. Take in the care homes and deaths in the community, and, according to the Financial Times, you need Chelsea’s home, Stamford Bridge. Meanwhile, a major spin operation involving the weight of government, MPs, sock puppets and social media sycophants was underway to rubbish a BBC Panorama programme which catalogued the government’s failure to buy proper protective equipment for frontline workers, even as they knew the pandemic was coming. It also exposed a level of trickery in the government’s oft-repeated claims to have delivered vast numbers of protective items that was frankly disgusting. So a pair of gloves is two items. Who knew? No gowns, visors, swabs or body bags were in their pandemic stockpile as the virus struck. But no story, because some of the interviewees had connections to people in the Labour Party.

So what did our frank, fearless and free papers lead on the next morning? ‘Testing, testing, testing,’ chirruped the Sun, as yet another testing pledge was wheeled out by Matt Hancock. ‘Millions can now get virus test,’ echoed the Express, conveniently overlooking the many such stories they had filed on tap in the past. ‘Key rule for lifting lockdown softened,’ was the Telegraph splash, celebrating yet more trickery, as the government changed its fifth rule for easing the lockdown from ‘not risking a second peak’ to ‘avoiding a second peak which overwhelms the NHS’. The Mail, meanwhile, had a full front page of self-congratulation: ‘£1m airlift for NHS Heroes.’

Fair play, the paper had set up a charity and gone into China and bought a million pounds’ worth of coveralls and masks. ‘Brilliant initiative,’ said Matt Hancock. Brilliant because…? Because almost two months into the crisis, charities and newspapers were doing something the government had consistently said it had under control.

Nor were the papers short of a nice photo with which to illustrate their down-page coverage of the death toll; Boris Johnson standing to attention in the cabinet room in the minute’s silence to remember the NHS frontline workers who had died.

The ones he had forgotten to mention the day before. Hours later, a baby was born, the media had another glorious chapter for the Johnson soap opera, and, to believe the same papers, a nation rejoiced.

Meanwhile, another baby was getting used to a very different life, one without her mother. 28-year-old Mary Agyeiwaa Agyapong, a nurse at Luton and Dunstable University Hospital, had died from Covid-19 shortly after her daughter was delivered by caesarean section around the time Johnson was admitted to hospital.

Not too late

I shall press on. What else to do? In common with millions of people, I am not a nurse or a doctor, I can’t run a power station, drive a lorry, or develop a vaccine, but when something is occupying most of your waking thoughts, it is natural to want to ‘do something’, not just sit there. And all I can do right now is watch, think, observe, then write and speak, and hope it is helpful to someone, somewhere.

It is still not too late for the government to change tack in terms of how they engage with the public and I hope it can be helpful to them, even now, if I suggest they adopt a different approach, based on the principle of ‘maximum openness for maximum trust’. They need a reset, and an apology for early mistakes, as president Macron of France has shown, is the best way to pivot to that reset. I don’t say that out of some desire for a great ‘Gotcha’ moment. I just believe it will help them to carry out the reset in approach that is needed.

So here, written on May 4, six and a half weeks after my own lockdown, is my latest memo, ever hopeful that someone in government with the ability to bring about change might read it, and make that reset happen. It is needed, because the UK has made dreadful mistakes, but, across the media and in much of politics, there seems little appetite to say so. But only if this is called out and admitted, I believe, can the UK hope to salvage anything from the mess. For them to claim success on the narrow question of the NHS not being overwhelmed is at best disingenuous, at worst insulting to all who died and all who worked to save the living.

1.) Say sorry for the early mistakes, but explain how hard it was when this thing first hit – people will respect and trust you more for it.

2.) Stop over-promising and under-delivering – it should be the other way round. The evident eventual success of increasing testing was actually undermined by the desperate massaging of the figures to be able to say a 100,000 target had been passed. And there is still no testing strategy.

3.) Stop parroting the line robotically that you are ‘following the science’. Science informs. It does not instruct. You make the decisions. Be clear about that.

4.) Explain the science. Share more data.

5.) Explain honestly the difficulties and the trade-offs being considered, between health outcomes and economic options, sector by sector.

6.) Involve parliament much more. (The Commons speaker objected to Johnson delaying the ‘major announcement’ of the government’s forward plan to Sunday, widely viewed as a way of avoiding tough questioning from MPs.)

7.) Set out how the test, trace and isolate strategy is intended to work, and give the country a breakdown of what tests are involved, how many of each kind are needed, and how and by when the necessary scale will be reached.

8.) Stop talking to the public as though they are idiots. Treat them as grown-ups.

9.) Dial down on the slogans and the clichés.

10.) Dial down the war talk.

11.) Dial up international co-operation.

12.) Dial up the empathy.

13.) Stop finessing the death rates.

14.) Put specific ministers in charge of the specific tasks arising from the crisis, regardless of their departmental brief.

15.) Indicate that the new-found respect for who and what key and essential workers are will be reflected in a revision of future economic and, indeed, immigration policy.

16.) Proactively get the non-Covid sick who are avoiding hospital to use the NHS now.

17.) Boost mental health capacity for the tsunami of psychological challenges that will flow from this.

18.) Admit that you can’t sort Covid and the future relationship with the EU at the same time.

19.) Confirm there will be a full independent public inquiry as soon as we are through the worst.

20.) Keep some of your best people out of the day-to-day crisis management and have them thinking ahead to the issues that you know are going to become major problems down the track, and set in train the work required to deal with them all.

I started on Good Friday 2020. Let me end on Good Friday 1998. In 30 years of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, 3,600 people died. At the height of this crisis, as many as that were dying over four days as a result of the coronavirus, in hospitals alone. Only the United States now stands ahead of us in the death stakes. That, on any judgement, is a failure.

That is how serious this is. We have been failed, both by government and by media, in that the response of both, in so many ways, has not reflected the scale of what has been happening. I sincerely hope the next stages of this are handled better than the first ones. For if anything, Phase 2 will be even harder than Phase 1, and the consequences of this crisis are with us now, for a long, long time.