The New European’s Editor-at-Large has a few tips for the prime minister when it comes to addressing the nation.

After writing here last week about crisis communications, and then watching a couple more of Boris Johnson’s daily press conferences, I posted a long blog on my website setting out how I felt the briefings could be improved. It was designed, genuinely, to be helpful, and I was pleased that messages came back from various parts of government that it was taken in that spirit.

As Michael White of these parts occasionally chastises me, I can sometimes let my Labour tribalism (broadly intact despite expulsion, though God I wish the leadership election was over), and my antipathy to Eton in general and Boris Johnson in particular, drive me over the top when writing about the Tories.

However this time, Mike sent me a nice email saying he felt the column here, and my subsequent 20-point list for improving the briefings, stayed the right side of well-intentioned advice born of experience dealing with cross-government crisis comms.

I won’t list the 20 points here. If interested in the detail, you can find them here but summed up, I was saying: more fact, more detail; less rhetoric, less bluster; cut the homilies and rambles; fewer snappy one-liners; more empathy for the dead and dying, and those caring for them; more explanation of decision-making processes; more linking of new policy announcements to previous ones, and to data; use graphics and film to explain; liven up format and broaden ministerial team; and, please, comb your bloody hair.

Barely had I hit the ‘post’ button than Catherine Rimmer, who headed my rebuttal and analysis team in Number 10 (brilliantly, see diaries volume 4) and is now CEO of Tony Blair’s Institute, sent me a weblink, with the simple message: ‘Just read your blog. Watch this. Masterclass’.

I clicked on the link to be taken to a press briefing conducted by a prominent US politician. Oh my, would it not be wonderful, would we not feel a little safer and less anxious if it had been a briefing by the president of the United States to which I was being directed. However, Trump’s briefings have made Johnson, never mind a Merkel or a Macron, look like a comms mastermind, what with the unadulterated racism inherent in his use of ‘the Chinese virus’ to describe the pandemic, (made while wearing his Chinese baseball cap) his petulance, his preening narcissism, his picking of fights with journalists asking reasonable questions, his use of experts not for their expertise but as backdrop and cover for his inconsistencies and ignorance, his inability to operate in any orbit other than one that has him, and him alone, at the centre.

So not Trump, but New York governor Andrew Cuomo, one of the many public figures Trump has attacked over Twitter in recent weeks as he seeks to cast blame and evade responsibility, the antithesis of qualities shown by real leaders.

If you have half an hour spare, I strongly urge you to go to governor.ny.gov and study the Cuomo briefings, especially if you work in comms, and especially if you work for Boris Johnson, or indeed any other leader currently in charge of the response of their nation or organisation. I have been sending video and transcripts to virtually every president and prime minister, minister, mayor or council leader I know.

Cuomo’s father Mario served three terms as New York governor, and is credited with one of the most famous quotes about campaigns ever made. ‘We campaign in poetry, but we govern in prose.’ His son’s briefings are indeed a masterclass in prose. Johnson, who as I said last week has struggled since becoming prime minister to make the switch from campaign mode to government mode, is fonder of the fancy flights of poetry than the hard grind of prose.

So why are Cuomo’s briefings the stuff of future crisis communications seminars?

First, tone and mood. Though wearing a polo shirt with state emblem, he looks good. He does not hide how serious things are – far from it – but he is calm, composed, polite, authoritative throughout.

Second, hard fact, and detail. The TV screen is split, on one side his face, on the other a presentation that he is clicking through, setting out with simple clear graphics the many facts of the crisis. Deaths. Cases. Testing. Capacity of the health system. Masks. Ventilators. Cuomo gives detailed area by area breakdowns of figures, points out trends, tries to explain them. He explains too how the various layers of government work together.

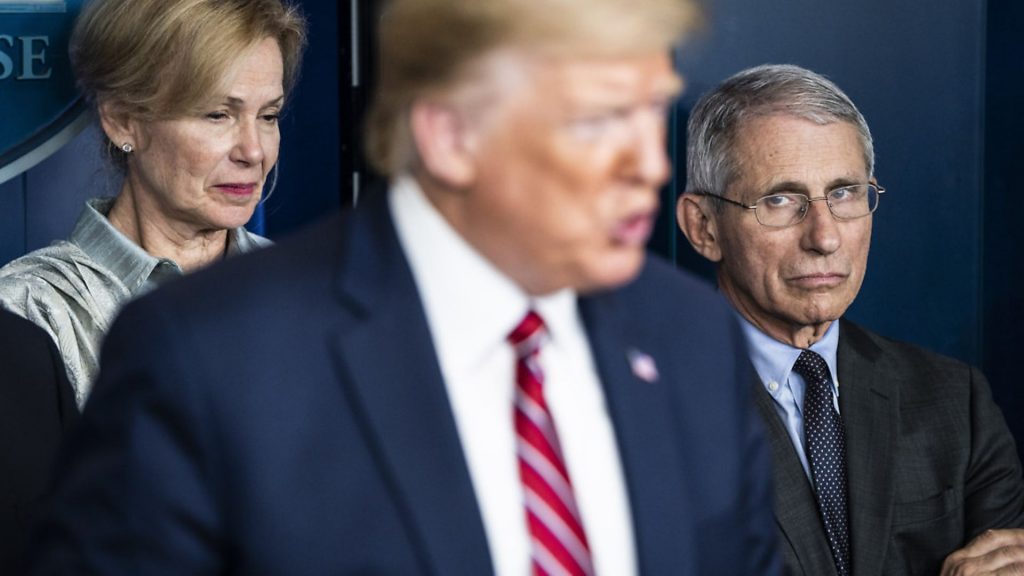

Third, empathy. He intersperses the factual presentation with regular sincere thanks to groups of people and to named organisations and individuals, including Anthony Fauci, the American immunologist who serves on the White House Coronavirus Task Force and has become known for his pained facial expressions as he stands behind Trump at his briefings, and is forced to listen to nonsense.

Fourth, thinking ahead. Cuomo was the first leader I saw openly to put concerns about mental health at the heart of his strategy, and he announced the plan for a network of online psychologists and psychiatrists. He showed empathy and humour. It was hard, he said, for families forced to spend day and night together. ‘It’s complicated… I live alone. I’m even getting annoyed with the dog.’

Fifth, inspiration. This is vital in a leader – it was inspiring to watch him. You felt part of his narrative. You felt the challenges were enormous, but confident they could be met.

Sixth, just the right amount of poetry amid the prose. Having devoted 25 minutes or so to hard fact and prosaic explanation, he saved a little bit of poetry for the end; about the acts of kindness and compassion by which we will be judged; about how life was going to go on, society was going to function, but things were going to be different; about how the crisis, as well as being a challenge to all of us, leaders and citizens alike, was also an opportunity to show what kind of people we were.

He closed as follows: ‘Last point is this, keep it all in focus. There’s a gentleman who used to be here who used to come through that back door, wheel himself through this room, get behind a desk, dealt with every hardship, raised himself up from a wheelchair every time he had to speak. Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He said most things better than anyone has said them since. He said – paraphrased – things are going to get worse and worse before they get better and better and the American people deserve to hear it straight from the shoulder. Tell the people the truth, tell them the facts. The facts are comforting. That’s my job and what I’ve been trying to do. These are the facts, this is the truth. I tell you the truth when it’s pretty and when it’s not pretty, but knowing the truth, I think, is reassuring. As I know the truth, I tell the people of the state the truth. That’s the first step, then we do what we have to do, and we will. Thank you, God bless you.’

He never mentioned Trump, but I am sure I was not alone in thinking of the president at that time. Trump has most certainly shown what kind of person he is during the crisis, and it is doubtful he is capable of changing his modus operandi let alone his character.

Johnson, however, still has time. His TV address to the nation on Monday was much better than his press conferences, and finally we got closer to the right place in policy terms. There was greater clarity, and clarity matters. But this is a long haul. And by the morning we were back to mixed messages about key questions like who should or should not be going to work.

I know Johnson is busy. I know he is facing enormous responsibility and making huge decisions that affect all of our lives. But I really do recommend that he takes half an hour to watch a Cuomo briefing, and five minutes to watch one of Trump’s. Then, when planning his own, and when he is out there in front of the country, try to operate by this mantra: ‘more like Cuomo, less like Trump.’

Have your say

Send your letters for publication to The New European by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk and pick up an edition each Thursday for more comment and analysis. Find your nearest stockist here or subscribe to a print or digital edition for just £13. You can also join our readers' Facebook group to keep the discussion and debate going with thousands of fellow pro-Europeans.