The campaign to ensure the government bails out the culture sector during the coronavirus crisis is another reminder of the complicated relationship between ministers and the arts, explains ADAM BEHR.

In 1982, an episode of Yes Minister featured a debate about arts funding between civil servant and establishment paragon Sir Humphrey Appleby and his more technocratic and demotic political counterpart, Jim Hacker.

‘Subsidy is about education, preserving the pinnacles of our civilization,’ stresses Sir Humphrey. ‘Let us choose what we subsidise by the extent of popular demand,’ counters Hacker. ‘It’s democratic.’

Covid-19, of course, has pulled the rug out from under Sir Humphrey’s beloved opera and Hacker’s preferred option of cinema alike, along with all points in between.

As the role of the state in all aspects of national life has been reconfigured on a historic scale, it has also thrown the broader role of cultural policy into stark relief. Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s rescue package of £1.57 billion is large by any measure (more than 20% of the total departmental spend by DCMS in 2016-17, including the BBC and lottery funding, for instance).

Such is the size of the crisis that this still won’t prevent losses within the cultural sector. The threat to cultural activity, on top of the way people have turned to cultural outputs to see them through the lockdown, are in one sense unprecedented. But they also reveal tensions and debates in debates in cultural policy that long predate Yes Minister.

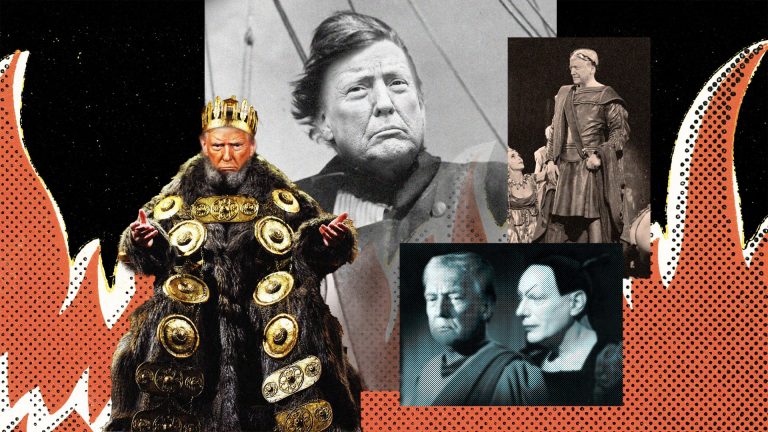

Prime minister Boris Johnson is fond of referring to Britain’s capacity for ‘world beating’ responses and, notwithstanding that this general tendency has older roots, at least some elements of this view can be traced back to the Second World War, especially given Johnson’s Churchill fixation.

As it happens, the cultural industries are a sector where Britain really does excel – it’s less easy to make that case for some of Johnson’s other claims – and elements of our current arts support infrastructure has its origins in the war, also the last time there was such a wholesale reshaping of the public provision.

While the BBC had obtained its Royal Charter in 1926, with a radio license in effect from 1923, the war brought the government into the arts themselves, as well as the means of broadcasting them.

The Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts was founded by a charity in 1939 to boost morale and provide work for touring artists during the war and when the treasury of the wartime coalition government agreed to fund it in 1940, the rationale included the ‘preservation in wartime of the highest standards in the arts of music, drama and painting’.

It also spoke of ‘widespread provision’ and support for more general enjoyment of the arts. But the emphasis was rather patrician – leaning towards Sir Humphrey over Jim Hacker.

The focus on bringing the ‘fine arts’ to the population at large carried through into the post-war Arts Council of Great Britain, the forerunner of today’s Arts Councils and chaired initially by John Maynard Keynes, who had been in post as the chair of CEMA since 1942.

The foundations of modern arts funding, then, were part of the post-war settlement, if perhaps more for the people than of them. The preference for high art over entertainment prefigured the future terms of ideological debate in cultural policy – how to balance fostering ‘excellence’ (and how to define that) against promoting access to the arts, and encouraging a plurality of voices.

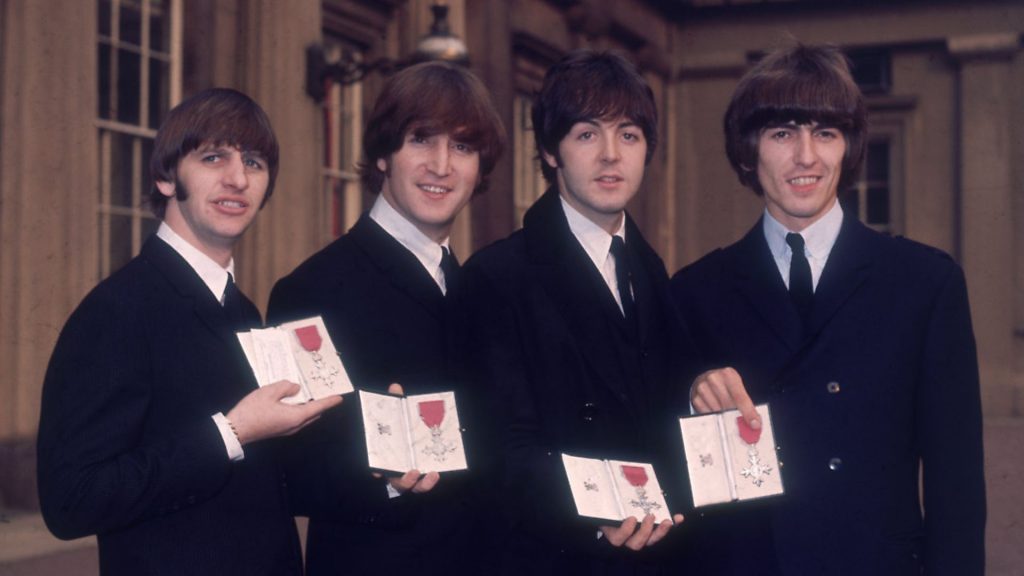

The 1960s saw the accelerating breakdown of deference within post-war society, and popular culture making a grab for high-art status as the likes of The Beatles breached boundaries between mass commercial appeal and serious critical acclaim.

This was of a piece with the Harold Wilson’s government overall, with Jennie Lee as the first minister for the arts and the introduction of the Open University.

As the wartime background to the Arts Council illustrated, it’s difficult to disentangle cultural policy from other areas. Many of the policies most salient for cultural activity don’t always refer directly to it, education being a core example.

Lee also expanded the parameters of the Arts Council, bringing forward the role of culture in tackling social exclusion and producing in 1966 the first White Paper on the arts, also the last for another 50 years.

Wilson the tactician was alive to the political potential of popular culture, and this too prefigured an approach to valuing culture that would become increasingly prominent.

The MBEs bestowed on The Beatles in 1965 provoked the ire of former recipients, several of whom returned their medals. War hero George Reed said that giving the award to the band meant ‘its meaning seems to be worthless’.

But amidst the debate it was noted that The Beatles were a major export for Britain, at a time when its industry overall was struggling somewhat. Wilson’s office referred to ‘the work these young people have done to diminish juvenile delinquency – especially on Merseyside’.

Economic contributions and social cohesion, then, emerged alongside a more explicit strand of ‘cultural policy’. In the end, John Lennon also demonstrated the limits of politicians’ capacity for corralling pop culture and in 1969 sent back his own MBE ‘in protest against Britain’s involvement in the Nigeria-Biafra thing, against our support of America in Vietnam and against Cold Turkey slipping down the charts’.

The tensions between the patrician and the popular may have taken a little longer to unwind, but instrumental values of culture percolated through national and local government, even as the post-war consensus ran into the sand in the late 1970s and Margaret Thatcher’s government of the 1980s turned towards free-markets and away from direct intervention.

Local authorities, many of them in conflict with the national Conservative government, turned to culture as a means of regeneration – to provide employment, and drive local industry.

Glasgow leveraged the European Commission’s City of Culture award in 1990 to similar ends while John Major’s government formed the Department of National Heritage in 1992.

After 18 years in the wilderness – and battling the Conservatives from town halls – Labour’s return to power brought the instrumental approach more fully into central government, presenting it as less a matter of subsidy than of investment.

This turn from ‘culture’ to ‘creative industries’ was made explicit by the re-tooling of the Department for National Heritage as the Department for Culture, Media and Sport.

This has played out through the detailed hashing out of policy and fraught debates about the limits of the market – in ticket touting, for instance – and concerns about the intrinsic value of art for art’s sake. The glitzier end of the process has had its ups and downs as well, from the soft power synergy of Cool Britannia to the awkwardness of Chumbawamba emptying a bucket of ice over John Prescott at the Brit Awards, and the lengthy travails of the Millennium Dome, ultimately resurrected as the O2 venue.

For all these difficulties, and although deindustrialisation means that issues of access and disparities between major cities and smaller towns remain salient, the New Labour years helped to embed culture within the broader economy. The apotheosis of this trajectory was perhaps the 2012 Olympic Ceremony foregrounding the UK’s popular culture, alongside the likes of the NHS, as emblematic of its national achievements.

As political scientist John Street has put it, ‘cultural policy – like all policy – is about allocating scarce resources and resolving competing demands’.

Navigating this in a crisis as simultaneously far-ranging and acute as Covid-19 remains fraught. ‘I guess everyone’s a Keynesian in the foxhole,’ conceded economist Robert Lucas – usually a sceptic about government intervention – in 2008.

And so it has proved, with industries across the board turning to the state. Cultural industries are no exception and, from ballet to rock to panto to stand-up comedy, rely on both venue infrastructure and a workforce heavily characterised by self-employment.

So the furlough scheme pertains as well as Sunak’s arts package. In one sense, Covid-19 has rendered Sir Humphrey and Jim Hacker’s debate moot. All of culture needs support at the moment. It has also shown, though, that economic and intrinsic value in the arts are hard to unpick, and that distinctions between social, economic and cultural policy are more diffuse than ever.