They might be fierce rivals, but Milan’s two football clubs have plenty that unites them. NEIL JENSEN reports on their complex history.

From Ferencváros to Feyenoord, modern football has left behind some of its big names of the past. But when it comes to clubs that once stood astride the European landscape, there are no bigger institutions among this band of fallen giants than AC Milan and their city rivals Internazionale.

Between them, the Italian pair have been European champions 10 times and have 36 league titles to their names. Yet, while Inter might be faring pretty well in Serie A this season, neither club has won any significant silverware for almost a decade and Italian football currently has just one team, Juventus, who can look Europe’s elite in the eye.

The slump in fortunes has been hard to take, not least because both clubs have a bitter rivalry with Juventus (one wrapped up not just in football, but also the political, economic and cultural competition that exists between Turin and Milan) that is almost as great as the one that exists between each other.

For if there is much to divide AC Milan and Inter, there is also much that unites them, not least the stadium they have shared for decades. The two clubs have a deeply intertwined history, with one emerging as a splinter of the other, and their periods or success and failure have often mirrored one another. The recent barren decade endured by both underlines this point, but it goes back further. The pair have finished in the top two in Serie A six times and have ended the season in consecutive places a remarkable 26 times.

This curiously conjoined history doubtless makes the rivalry on the pitch and in the stands all the more intense. The so-called Derby della Madonnina – named after one of the city’s principal attractions, the statue of the Virgin Mary which sits atop the Duomo – is among the fiercest in world football and historically one of the best-matched.

Like many local rivalries, people try to inject some form of social or class differentiation between the two clubs involved. In truth, any such distinction has now evaporated. But it was there at the beginning. AC Milan’s support was said to be primarily working class and it used to have a strong trade union influence.

Their blue collar background led to their first nickname, Casciavit, the screwdrivers. Milan, now more popularly known as the Rossoneri (literally, ‘the Red and Blacks’), actually have English origins.

Established in 1899, they were a football and cricket association and adopted the English spelling of the city’s name – Milan, and not the Italian Milano. Mussolini’s regime forced the club to change, although it later switched back.

Inter, meanwhile, were founded in 1908, becoming a breakaway club from AC Milan following the death of the club’s influential Nottingham-born founder Herbert Kilpin. The split was precipitated by a disagreement over the acceptance of foreign players – some AC Milan members wanted the club to be more Italian-centric. The result was that eight members, all Swiss, helped to form Internazionale, the very name indicating its different approach to AC.

From its beginnings, then, Inter had a more cosmopolitan reputation and became associated with a more well-heeled audience. In its early days, the side was nicknamed bauscia, a Milanese term meaning ‘braggart’ to reflect their supposed snooty, bourgeois credentials.

During the Fascist period, the club was forced to merge with Union Sportiva – Milan was one of the hotbeds of support for Mussolini, who used football as an effective propaganda tool for the masses.

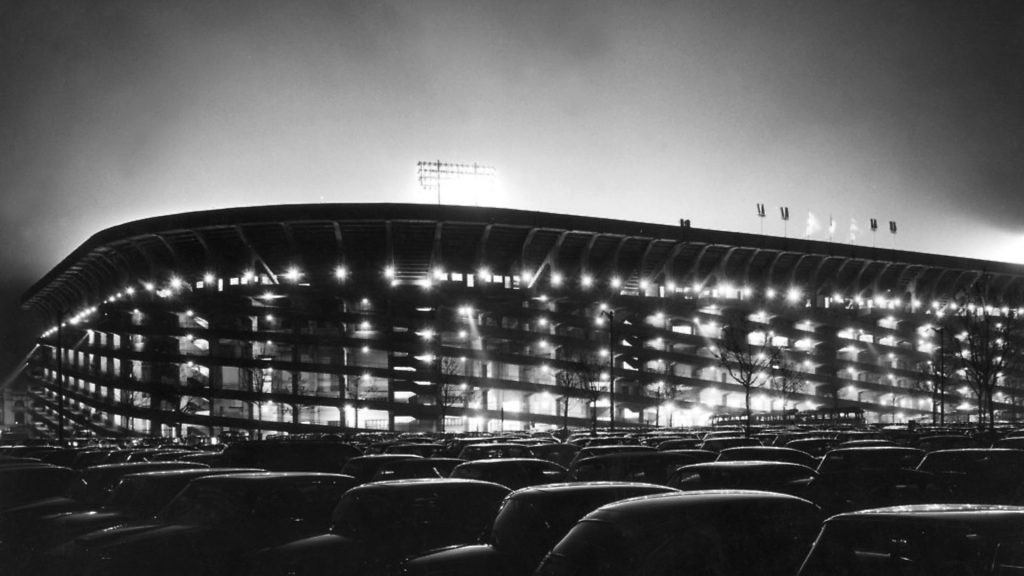

After the war, the two teams began their cohabitation at the San Siro, when Inter moved in, in 1947. (They had previously played in the vast, crumbling, neoclassical Arena Civica, still used by Milan’s third team, Brera Calcio).

The San Siro had been AC’s home since its construction in 1926 (its inaugural match was a clash with Inter, who triumphed 6-3). It took its name from the surrounding neighbourhood, just to the north-west of the city centre, which also features a horse-racing track, which still exists and which was owned by the AC Milan president.

When the club had the stadium built it’s design differed significantly from other Italian football grounds – which were mostly built with public funds – in that it did not incorporate a running track around the pitch.

The switch to ground-sharing intensified the rivalry, which emphasised the contrasting social backgrounds of the club’s fans. Inter supporters became known as motoretta, as they were able to travel to the ground on motorscooters, while their AC counterparts – tramvees – had to rely on public transport.

It was during this early post-war period that Italian clubs took a lead in becoming increasingly professional. Both Milan clubs were at the forefront of this and became leading exponents of the infamous ultra-defensive and often strong-armed approach known as catenaccio, which translated to the rather ominous ‘door bolt’.

This often notorious style, which actually originated in Switzerland, was largely pioneered by two domineering Milanese managers in Nereo Rocco of AC and Inter’s somewhat mysterious Helenio Herrera.

Through connections in the UK, notably the popular ‘Mr Fix-it’, Gigi Peronace (the man described as England’s first real football agent), Italian clubs started to sign British players, although the demands and regimentation, not to mention the invasive media, proved too much for them. Catenaccio, for a while, dominated Europe, with Milan (1963) and Inter (1964 and 1965) ending the Real Madrid stranglehold on the European Cup.

Inter, in particular, had a golden period that earned them the title, Grande Inter, with a team that included all-time greats Giacinto Facchetti and Sandro Mazzola.

A more expansive style was to succeed the cautious and cynical tactics of the Italian clubs but it was not until the late 1980s that a new generation of coaches and players took AC Milan and Inter back to the very top.

In the case of AC Milan, the arrival of the controversial Silvio Berlusconi in 1986 transformed their fortunes and gave them a huge advantage over their rivals. Berlusconi put Milan on a different commercial plane to the rest of Serie A and brought a host of international stars to the San Siro, including the Dutch trio of Ruud Gullit, Marco van Basten and Frank Rijkaard.

With a new coach, Arrigo Saachi, appointed in 1987, Milan played inventive and exciting football, winning two European Cups in 1989 and 1990.

Milan’s multi-national team, along with Diego Maradona at Napoli, were the faces of a glamorous, carnival-like Serie A. Inter, too, grasped the opportunity and with a German-orientated team, won the title in 1989. In 1995, the club got its own high-spending owner, in the form of petroleum tycoon Massimo Moratti. The two clubs competed with each other – and Juventus – to be the most glamorous and successful during a golden period for Italian football. Milan’s 1994 Champions League win, an era-defining 4-0 victory against a strong Barcelona team, appeared to be the zenith of their achievements.

In some ways, the Milan sides’ cosmopolitan all-star line-ups provided a blueprint for the Premier League in England. While Italy’s domestic competition started to decline in the 21st century, partly due to a series of scandals, but also because of increased competition, the England’s Premier League became the go-to competition in Europe.

The signs that the Milan clubs and Italy’s other leading sides were losing their appeal, and their financial clout, became evident when rivals from other countries started to lure players away, such as Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Thiago Silva who moved from AC Milan to the emerging Paris Saint-Germain in the summer of 2012. In the past, such a move would have been almost unthinkable.

The financial crisis of 2008 had a big impact on Italy and its economy, so given most clubs were owned by Italian families or wealthy individuals, it was inevitable they would be affected.

Both Milan giants hung onto players for too long and struggled to replace ageing squads. The timing of their decline and lack of investment was unfortunate. In an age of increasing broadcasting fees and new, extraordinarily wealthy owners, AC Milan and Inter, along with most Italian clubs, could no longer compete with the new European elite. The evolving landscape was effectively relegating Italy from the very top bracket.

Berlusconi stayed with AC Milan until 2017, by which time his wealth had been significantly eroded. He sold the club to Chinese investors, but in a complicated chain of events, a private equity firm, Elliott Management, now owns AC Milan. Inter have also moved on from their links with the past, the Moratti family finally selling its complete holding in the club in 2016 to Indonesian businessman Erick Thohir. Angelo Moratti had been chairman between 1955 and 1968 and his son, Massimo, filled that role from 1995 to 2013, spending almost 1.5 billion euros of his money in the transfer market. The club is now majority-owned by Chinese holding company Suning, the owner of which, Zhang Jindong, is now chairman of Inter.

Of the two, Inter would seem to have the brightest near-term future. They recently announced record revenues and they remain the biggest spectator draw in Italy with almost 60,000 people turning up for their home games at the San Siro. They also have serial winner Antonio Conte as their coach and they’ve matched their ambition to become a credible challenger to Juventus with a number of high profile signings in the summer of 2019.

AC Milan are also under new management and have retained their support. The much-travelled Marco Giampaolo joining the club as coach in June 2019, replacing Gennaro Gattuso. After recently running into Financial Fair Play problems, AC Milan spent around 100 million euros to strengthen their squad, but it has been a difficult campaign so far. Inter and AC Milan have already met this season and Inter ran out 2-0 winners. At this early stage, Juventus will be more wary of the blue and black half of the San Siro.

One major part of the route back to pre-eminence for both clubs is a proposed move to a new stadium – one which they will continue to share.

Although AC Milan built the San Siro, they sold it to the local council in 1935. Municipal-owned stadiums are common in Italy, but this model of ownership means the sites are often under-utilised, with limited commercial scope.

The San Siro – also known as the Giuseppe Meazza in honour of an Inter legend, who also played, briefly, for AC – has been one of world football’s great venues and a cutting-edge one for much of its life. But it now looking increasingly tired.

It has undergone various alterations through the decades, including for the 1990 World Cup. This involved the construction of 11 concrete towers around the outside, four of are located at the corners, supporting a new roof, with distinctive protruding red girders. At one point, its capacity was increased to 100,000, but it is currently 80,000 – still the largest in Italy.

Under plans now being discussed, a new stadium will be built in the same area (though with a reduced 60,000 capacity). The design has yet to be decided upon, but after lengthy discussions, the wheels are now turning. Whether it will give these peculiarly inter-connected clubs the impetus they need to return them to the European football’s elite remains to be seen.