The Olympic year represented a high point for a self-confident and outward-looking United Kingdom, says Sophia Deboick.

Britain felt like a truly hopeful place in 2012. We were Olympic hosts and it was a royal jubilee year, promising plenty of unthinking flag-waving. Bradley Wiggins won the Tour de France and even if Andy Murray fell at the final hurdle at Wimbledon, the nation finally took him to their hearts as he showed his human side by breaking down in the post-match interview.

Despite some controversy – from ‘cash for access’ and the final convictions in the MPs’ expenses scandal to Chris Huhne’s speeding case and Eric Joyce swinging punches in a House of Commons bar – politics did not distract from this sense of success.

The election of two years before had resulted in what now seems like the very minor crisis of a hung parliament and the civilised compromise of a coalition government which was trundling along nicely. The Tories too had become humanised, David Cameron announcing the fast-tracking of legislation for equal marriage and apologising for Section 28.

Following the previous October’s defeat of a Commons motion calling for a referendum on EU membership by 483 votes to 111, the debate on Europe had gone quiet and, for now, Britain had the luxury of exploring its identity through celebration rather than adversity. All eyes were on a jubilant nation in a year of huge public concerts and internationally-successful British acts, even if one outlier exploded out of the east to achieve world domination.

The opening and closing ceremonies of the 2012 Olympics were a lesson in harnessing music for a powerful shared emotional experience. Long-time collaborators Danny Boyle and ceremony musical directors, electronic duo Underworld, used a broad sweep of British music in the opening ceremony – the soundtrack ranged from Elgar’s Nimrod to the Sex Pistols’ Pretty Vacant – in a programme that was never triumphantly nationalistic but rather a celebration of tangible achievements and the pioneering spirit that drove them.

During a 15-minute mega-mix of British pop music it was grime, of all genres, that was the joyful highlight, as Dizzee Rascal’s Bonkers exploded and the stadium broke into dance. Boyle and Underworld also found room for the more esoteric, as the euphoric yet fragile ambient track Olympians by imaginatively-named Bristolian electro team F**k Buttons was used to brilliant effect in the athletes’ parade, while their more angular Surf Solar had featured earlier in the ceremony.

Underworld’s original composition for the ceremony, Caliban’s Dream, was performed by Two Door Cinema Club’s Alex Trimble as the Olympic cauldron was lit. Devastatingly beautiful, the song used the ultimate musical emotional manipulator – a children’s choir – and only the bored-looking Queen remained unmoved.

The opening ceremony soundtrack was so perfectly calibrated that the live performances of the closing ceremony seemed clunky in comparison, many of the performers struggling to make an impression amid the tumult and scale of the stadium, although Annie Lennox’s entrance on a huge galleon flanked by gothic Victoriana-styled dancers, and both Ray Davies and the Spice Girls emerging from black cabs for their performances were memorable bits of stagecraft.

The Paralympic opening ceremony, meanwhile, saw Stephen Hawking don Orbital’s trademark head torches to deliver a monologue about the Large Hadron Collider as the band performed their Where Is It Going?, which segued into Ian Dury’s provocative protest against patronising attitudes towards disability, Spasticus Autisticus. Inventive, daring, and, above all, unfailingly entertaining, the Olympics ceremonies far outclassed June’s Diamond Jubilee Concert at Buckingham Palace.

Olympic headliners, rock heavyweights Queen and The Who, were swapped for Elton John, Cliff Richard and Gary Barlow in a staid programme which couldn’t have been further from Boyle’s risk-taking. Madness singing ‘Our house, in the middle of one’s street’ as a projection turned the palace into a high-rise block was just all wrong, and only the unforgettable spectacle of a 64-year-old Grace Jones wearing a PVC bustier and hula hooping her way though Slave to the Rhythm stood out as a genuinely awe-inspiring moment. The Olympics ceremonies had been chock full of them.

For all this focus on Britain, this was the year that the pop scene of another part of the world came into the consciousness of the west. South Korean rapper Psy had been around for more than a decade and was a controversial figure in his own country, having attracted bans for explicit lyrics, been embroiled in a national service draft-dodging scandal, and scored four domestic No.1s, but 2012 was the year he went global.

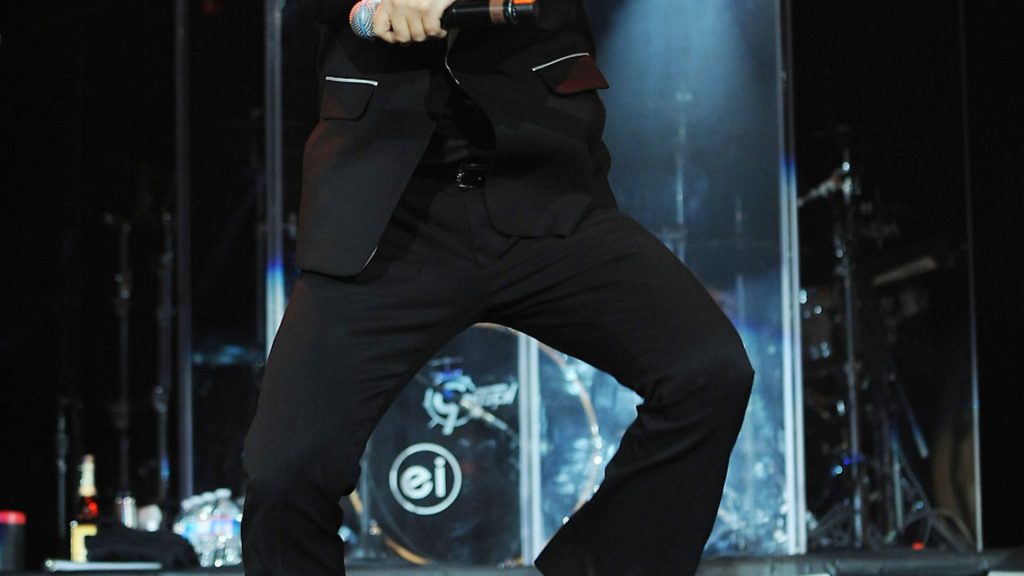

The dangerously infectious Gangnam Style swept the globe as its unhinged video featuring distinctive horse-riding dance moves went viral, and in early October the song peaked at US No.2 and reached UK No.1. The rest of Psy’s year was as crazy as the song itself. He performed Gangnam Style as Madonna’s guest at her Madison Square Garden show. He met Ban Ki-moon at the UN, the secretary general bemoaning the fact he was no longer the world’s most famous Korean. He addressed the Oxford Union while wearing sunglasses throughout. President Obama mooted the idea of doing the Gangnam Style dance at his inauguration ball if re-elected, while Boris Johnson claimed at the Conservative party conference that he had done the dance with David Cameron. Psy ended his year by appearing at Times Square on New Year’s Eve, and if 2012 had belonged to one performer, it was him.

Gangnam Style came off like a novelty one-hit wonder which, like all truly mad pop hits, used its accompanying dance moves as a central part of its contagious effect. But it had more to it than inane catchiness and danceability. For one thing, Psy’s look – a tubby schoolboy in bow tie and retro suit – was a world away from the incredibly heightened aesthetic of other K-pop artists, and the stylised video presented a fully-fledged post-modern icon that gave Lady Gaga a run for her money.

The song’s lampooning of the conspicuous consumption in Seoul’s upmarket Gangnam district, and of the wider ambition to ostentatious living of South Korean society, made it more than a mindless pop hit. By the end of the year the song had reached a billion views on YouTube – the first video to do so – and even if it took a hit that was uncharacteristic of the genre to do it, it all added up to the whole world waking up to K-pop. The British breakthrough of K-pop boyband BTS this year, as they sold out two nights at the O2 and broke the UK Top 40, is evidence that the process is still gathering pace.

Britain was still proving its enduring pop credentials this year. Having been thrown together in the adverse circumstances of The X Factor and gone on to win the show, Little Mix proved their power as a girl band with enough genuine talent and slickness to break America. Already, their first two singles, Cannonball and Wings, had been British No.1s, but by June 2013 their debut album DNA, released in November the previous year, reached US No.4, making them the first British girl group ever to debut in the Top 5 with their debut album. They had sold two million records worldwide by that time.

Meanwhile, Adele went out with a bang before taking a three-year break. Having won awards galore, including in all six categories she was nominated for at the 2012 Grammys, broken all sorts of records and shifted shedloads of albums, the theme she co-wrote for October’s Bond-fest Skyfall would win a Best Song Oscar, a Grammy and a Golden Globe, as well as a Brit Award. Her male counterpart for mega-selling easy-listening pop, Ed Sheeran, had appeared at both the Olympics and Diamond Jubilee events and his hit debut album of the autumn of 2011 set him up for much time in the spotlight in 2012, bagging two Brits and an Ivor Novello, as well as writing for One Direction and Taylor Swift and breaking America. These acts represented British success on a massive scale in 2012.

While the House of Commons had decisively defeated the idea of an EU referendum back in 2011, with 81 Tory MPs supporting it and a further two abstaining it was the largest-ever Tory rebellion over Europe, and UKIP’s record results in May 2012’s local elections was proof that the spectre of euroscepticism had hardly gone away.

The start of 2013 would be marked by David Cameron making an in/out referendum a future manifesto promise, and the dream of a world-leading, proud but not boastful Britain presented in the Olympics ceremonies would die in the Brexit-fuelled flames of xenophobia, British exceptionalism and post-truth politics that followed. In 2012 we had never been more confident but, crucially, that was a confidence that was outward-looking and generous – qualities in short supply today.

Find the accompanying playlist on Spotify. Just search New European: 2012.