Singers started to unbutton, and America got a taste for adultery. SOPHIA DEBOICK on a saucy year in music

Not quite a decade into the 20th century, Europe was grasping the nettle of progress. In 1909 Shackleton got closer to the South Pole than anyone had yet achieved and Louis Blériot flew across the Channel. The first colour film, in Brightonian George Albert Smith’s Kinemacolor, made its debut in London, while Georges Méliès was busy pioneering cinema in Paris, making no fewer than nine films that year.

The plastic age began when Bakelite, a Belgian invention, was unveiled. In Britain, social progress accelerated rapidly as the Liberal Party launched a raft of reforms. The old age pension, the minimum wage and the labour exchange were all innovations of 1909, while the People’s Budget sought to redistribute wealth and the Children Act brought a wave of protections for the young.

Meanwhile, the suffragette campaign, halfway through its life, faced the first incidence of force-feeding of a hunger-striker in September as it fought for women’s right to participate in a politics that was proving itself a powerful force for change.

British music and entertainment too was changing. Music hall was in its twilight years, with both Harry Champion’s Boiled Beef and Carrots and Mark Sheridan’s I Do Like To Be Beside the Seaside of this year notable recordings of its late period. But music hall’s irreverent spirit lived on across the channel in American vaudeville and the hits of the sheet music and early recording industry that it spawned. And while hemlines were still long and women yet unemancipated, any idea of a hangover of Victorian values was disabused by vaudeville’s turn away from a cloying 19th century sentimentality, the fruity hits of 1909 instead revelling in stolen kisses, amorous embraces and sexual temptation.

Henry Burr was one of several male proto-pop stars who worked prolifically in this period, recording thousands of songs during his career. The Canadian singer, who made great play of his Irish ancestry, with an affected accent and hits riffing on the Irish theme, released the melancholy I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now? in September, a song that had appeared in the Broadway musical The Prince of To-Night earlier in the year.

The song was profoundly preoccupied with the diversion of the amorous intentions of a former beloved to someone new, asking ‘I wonder who’s buying the wine for lips that I used to call mine’. But this was quite tame stuff compared to Burr’s Honey on Our Honeymoon: ‘Come honeymoon, come love and spoon/ Honeymoon with me my honey/ My own sweet honey/ My sugar honey.’ Love as an enduring pop theme had, it seemed, been usurped by lust.

Vaudeville star and hugely successful early recording artist Billy Murray would record I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now? the following year as it began its journey to becoming a standard, later covered by everyone from Perry Como to Ray Charles, but 1909 was particularly eventful for Murray.

He signed contracts with both Victor and Edison, putting out recordings on both the shellac discs adopted by Victor and the more primitive Edison cylinder. Murray’s By the Light of the Silvery Moon, written by Polish-born Broadway composer Gus Edwards and Two Little Boys lyricist Edward Madden, had been a hit on stage in 1909 in both the Ziegfeld Follies and the very short-lived show Miss Innocence, and featured another keenly amorous lyric: ‘By the light of the silvery moon/ I want to spoon, to my honey I’ll croon love’s tune.’

Even Murray’s essentially self-pitying I Wish I Had a Girl proclaimed ‘I’d like to do some kissin’ and some huggin’/ Some croonin’ and some spoonin’ too I guess’, while Good Evening, Caroline ended up with ‘stealing kisses in the moonlight’, highlighting the coyness that gave these songs a sense of the illicit thrill.

Billy Murray had for some years formed a partnership with Lancashire-born Ada Jones, the two recording a number of duets together in 1909, including the Indian-themed Blue Feather (March’s Crazy Snake Rebellion was a reminder that the American Indian Wars rumbled on), and the un-PC novelty hit The Boy Who Stuttered and the Girl Who Lisped, but Jones also proved that female singers too jumped on the racy hits bandwagon that year.

While Jones’ solo recordings of the show tunes I’ve Got Rings on My Fingers and My Pony Boy were successful, her biggest hit of 1909 was the slightly unnerving The Yama Yama Man. This song about a bogeyman figure had been made famous on stage by vaudevillian Bessie McCoy, but Jones’ version changed the lyrics to add further spice to the already daring reference to ladies flashing their ankles as they gathered up their long skirts off the dirty pavements: ‘The Johnnies they go to see the play/ But they don’t care for the plot/ They want to see if all the girls/ Are wearing much or not.’

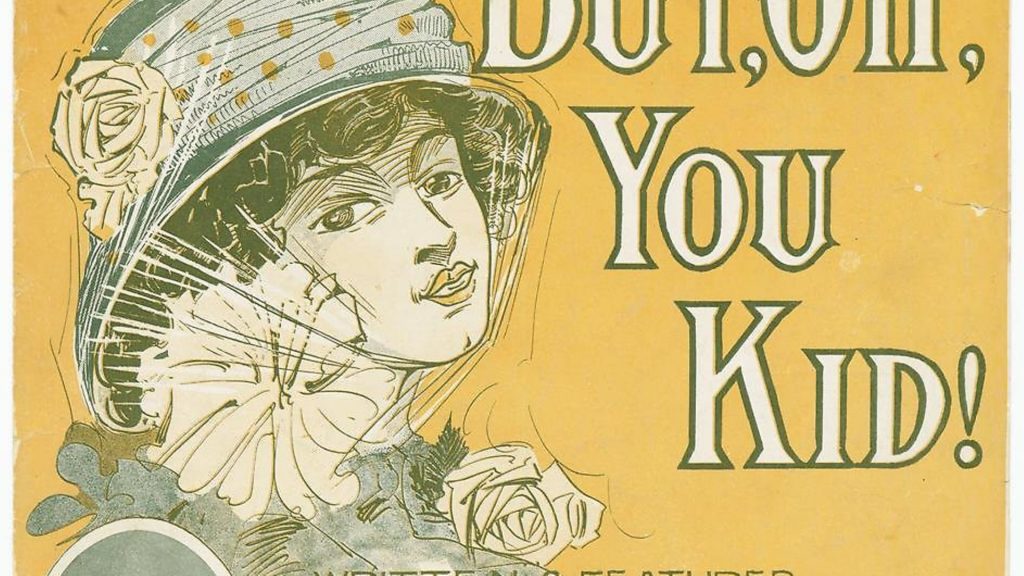

Partial nudity was one thing, flagrant adultery quite another, and the hottest record of the year was one that celebrated temptations to extra-marital amorousness to a degree hithertofore unseen – or unheard. Written by million-selling composer Harry Von Tilzer, I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife – But Oh! You Kid! featured the protagonist ‘Jonesy’ who picks up a ‘sweet girlie’: ‘Jonesy stopped and spoke to girlie/ Just as old friends often do/ And he said, ‘I’m married but’/ ‘That ‘but’, my dear, means you’/ I love, I love, I love my wife – but oh, you kid!/ For my dear wife I’d give my life – but oh, you kid!’

But before we begin to feel too sorry for the eponymous wife whose husband has a roving eye, it turns she is also at it: ‘Now Jonesy’s wife and butcher man each morn would chat/ This butcher too was married but she didn’t mind that.’ As New York Times writer Jody Rosen recently put it, I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife – But Oh! You Kid! ‘played sexual brazenness for laughs’, and as such was ‘a generational marker, an anthem of changing times’, and the way the title quickly became a widely-quoted catchphrase was also a sign of growing commercialisation.

Adorning all manner of consumer items and used to sell anything and everything (‘I love my wife, but oh! You pretzel!’), it became ubiquitous, and versions of the song were monster hits for vaudevillians Arthur Collins, ‘Ragtime’ Bob Roberts and Edward Favor.

It also inspired other songs with a comic take on domestic discord. The rather heartless My Wife’s Gone to the Country! Hurrah! Hurrah! was the first big success for Irving Berlin, in this year still a staff lyricist at the Ted Snyder Company music publisher.

The song incorporated this catchphrase that was all the rage and was cut by prolific recording star Frank C. Stanley, as well as Bob Roberts and Arthur Collins with singing partner Byron Harlan.

Collins and Harlan were known for another genre that had long dealt with supposed immorality, but made it socially acceptable by making black Americans its protagonists.

This was the era of the minstrel show – Al Jolson was early in his career as a member of Lew Dockstader’s celebrated minstrel troupe in 1909 – and Collins and Harlan were keen propagators of the now offensively-termed ‘coon’ songs from such shows.

They released Down Among the Sugar Cane on Edison in March, while Collins’ September solo release That’s A Plenty also found the white singer mimicking a ‘negro’ dialect. While Collins and Harlan were pioneers in some respects – they were the first to record Alexander’s Ragtime Band and to mention ‘jazz’ on record – this racial stereotyping renders their back catalogue monstrously archaic.

These songs are a reflection of the times, and it was in the face of segregation, disenfranchisement and racial violence that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was founded in February 1909, the first step in the civil rights struggle.

A future anthem of that cause, Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, had been written by freed slave Wallace Willis in the mid-19th century but was only recorded for the first time in this year. It was particularly poignant in its yearning for deliverance to a homeland in this period, equidistant between the abolition of slavery and the civil rights laws of the 1960s, where there was still a very long way to go to the promised land.

In May 1909, Britain’s Daily Mail, chief cheerleader in a vogue for anti-German sentiment, claimed ‘Germany is deliberately preparing to destroy the British Empire’, the dénouement after its wildly popular serialisation of William Le Queux’s lurid fictional account of a future German invasion. Such hysteria fuelled popular appetite for a war of unimaginable devastation that would remake Europe and beyond, redrawing borders and, indeed, ending empires.

But that war would also hasten a social revolution that was already straining at the leash in the short but sweet interlude between the end of Victoria’s reign and the dawn of the age of mechanised conflict.