The English Renaissance took music into new directions and saw that emergence of a tune which still echoes down the ages. Sophia Deboick reports.

Elizabeth I had been on the throne for more than 20 years as the 1580s dawned, and was presiding over a peaceful England. But these years were the calm before the storm. After the horrific persecutions under her Catholic sister, ‘Bloody’ Mary, the nominally Protestant Elizabeth made it clear she had no wish to ‘make for herself a window into men’s souls’ and brought religious tolerance and a sense of stability.

By the late 1570s she was fast consolidating her image as the austere Virgin Queen and the protector of her people, with dominion not only over her own lands but also over the seas. As the shape of the world rapidly changed, her advisor, occultist John Dee, had a vision of English naval power being used to build an empire to rival Spain’s. That January, on the heirless death of Cardinal-King Henry ‘the Chaste’, Philip II took the Portuguese crown and added its possessions in Africa and India to his existing ones in Europe, the Americas and the Philippines. Philip – Elizabeth’s former brother-in-law and one-time suitor – was busy championing Mary, Queen of Scots for the English throne just as Sir Francis Drake made his triumphant return to Plymouth on the Golden Hind in September after circumnavigating the globe and English dreams of naval power intensified. The stage was set for an epic confrontation on the seas at the end of the decade.

For the arts too, horizons were expanded under Elizabeth, and the start of the 1580s contained the seeds of coming musical change. Elizabeth rejected the extreme restrictions of Puritanism and embraced the ritual and beauty of Catholicism, a configuration which could only aid the flowering of the English Renaissance. Under a queen who was herself an accomplished musician and keen dancer, new music thrived. There was a new emphasis on secular music in the vernacular, and polyphonic vocal music and instrumental music flourished. In this year two of the most important composers in British musical history were active, the advent of commercial theatre hinted at a new context for musical performance, and a song appeared that would echo down the ages, courtesy of ice cream vans and telephone hold music.

The best-known song of the Tudor period is one most people would attribute to half a century and three monarchs before 1580. In September of that year, the lyrics of Greensleeves were registered as a broadside ballad with the London Stationer’s Company by printer Richard Jones as A New Northern Dittye of the Lady Greene Sleeves. The tune that went with it, which survives in slightly later sources, reveal that it was written in the Spanish romanesca style, which was unknown in England until after Henry VIII had died, sadly scuppering appealingly romantic notions that Henry wrote it for a coy Anne Boleyn in a fug of emotional torment. But that tune was evidently so successful that it was endlessly adapted.

Twelve days after the original was registered, a religious version appeared, described as Greene Sleves moralised to the Scripture, declaring the manifold benefites and blessings of God bestowed on sinful man, and three days later another set of lyrics titled Greene Sleeves and Countenance appeared. In December, Richard Jones registered A merry newe Northern Songe of Greene Sleeves with the opening line ‘The bonniest lass in all the land’. Even if the putative backstory doesn’t quite add up, Greensleeves speaks to the universal power of a good tune, and it’s been with us ever since.

Such adaptability was a feature not only of music itself, but its creators in the turbulent English 16th century. Thomas Tallis, in his mid-70s in 1580, had made malleability a survival strategy, managing to ride the violent wave of religious change throughout his service as a Gentleman of Hampton Court Palace’s Chapel Royal, where he was composer and performer to Henry VIII and all three of his monarch progeny.

As a Catholic and innovative composer of polyphonic works, Tallis came up against Calvinistic restrictions on church music at the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign. The new emphasis on the Word of God and the liturgy as a ‘work of the people’ meant the whole congregation participated in the call and response of the service, not just the clergy, and the 1559 Injunctions, which laid down rules for worship, restricted the use of polyphony, saying that the words must be ‘playnelye understanded, as if it were read without singing’.

But, in a mark of the degree of tolerance regarding religious observance that existed under Elizabeth, the Injunctions went on to say that ‘nevertheless for the comforting of such that delight in music’ any song of praise ‘in the best sort of melody and music that may be conveniently devised’ was permitted before or after the formal service.

Tallis’ more complex compositions found an outlet in such a context, and as he had been granted a royal patent for printing music which amounted to a monopoly, these works also found their way into homes via the incipient commercial market in music. Despite his Catholic faith, Tallis wrote for Protestant services in the Chapel Royal and his harmonised versions of the plainsong responses of the church service are still used by the Church of England to this day.

William Byrd, joint holder of Tallis’ music printing patent and fellow Gentleman of the Chapel Royal from 1572, challenges his colleague for the title of most renowned composer of the age. With a career total of nearing 500 compositions and an ability to both synthesise disparate influences and transmit a personal style, Byrd was a musical titan.

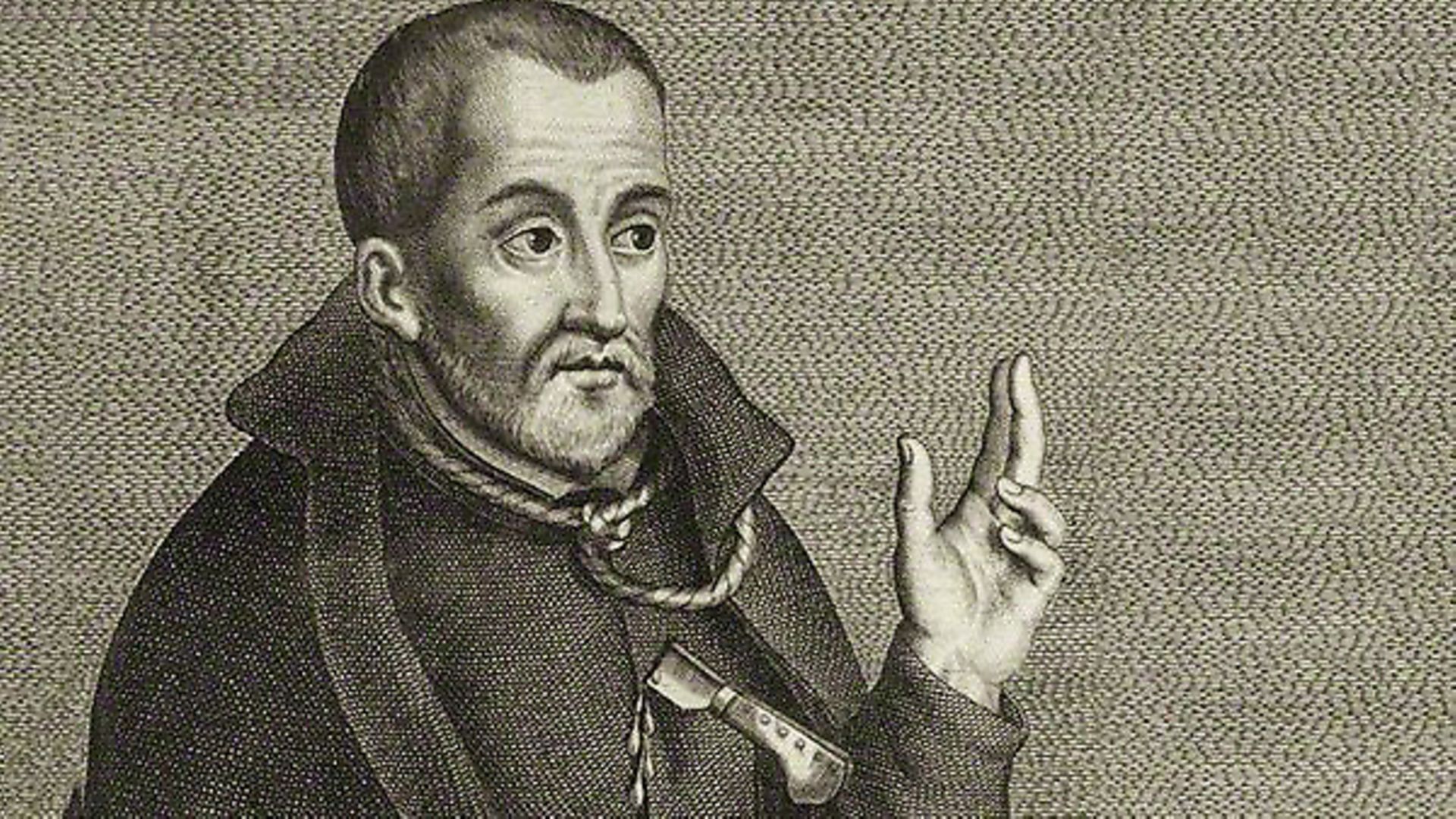

In 1580 he was turning 40 and had recently converted to Catholicism. He would soon be listed as a known Catholic recusant, appearing in a catalogue of their haunts as one of the ‘relievers of papistes’, and his conversion had a profound impact on his music. His motets (a form of sacred choral music) began to take up themes of the persecution of the chosen people, the Babylonian and Egyptian captivities, and martyrdom. Indeed, in the context of ever-present threats to her position, Elizabeth’s religious latitude hardly precluded horrendous executions, as the 1581 hanging, drawing and quartering of Jesuit Edmund Campion, who arrived on a mission to England in June 1580, proved.

Campion was probably the inspiration for Byrd’s setting of Psalm 78, Deus venerunt gentes, which spoke of ‘the dead bodies of your servants as food for the birds of the sky, the flesh of your saints for the beasts of the earth.’ Despite such ardent espousal of the Catholic cause, Byrd would write significant pieces of Anglican church music, just as Tallis did, including his Great Service of the following decade. The Elizabethan age was one where creative ability trumped religious identity. The golden age of Elizabethan theatre was not yet in full flow, but it was fast on its way in 1580. While the first permanent theatre buildings in England had appeared in the 1570s, the famous Southwark theatres – the Rose, the Swan and the Globe – would only be established over the 20 years after 1580, and commercial theatre was in its earliest infancy. Shakespeare was but 16 in this year and little is known about his life at this time. As the eldest son, and having left school two years earlier, he must have been engaged in some sort of gainful employment, particularly as there is extensive evidence of his glove-maker father’s money troubles. It’s unclear whether the young William would have had the leisure to go and see the touring troupes of players – the retainers of prominent noblemen – who performed in Stratford in those years. Lord Strange’s men and Essex’s men performed in 1578, Berkeley’s men in 1580, and Worcester’s men the year after. The precise details of the performances put on by these companies are lost to history, but just as music had played a part in the itinerant medieval mystery play tradition, music in all likelihood was performed either side of performances as well as at points during them. These troupes were important forerunners of the theatre of the Shakespearean age, where music on the recorder, lute, viol, hautboy, trumpet, drum or fife was used prominently in the staging to set moods of courtliness, ominous drama or warlike doom.

The English Renaissance would reach its imperial period just as tensions with Spain boiled over and the Spanish Armada of 1588 menaced the country. Persecution of Catholics had already increased by that time. The fine for not attending Anglican services went up from 12 pence a week to a punitive £5 a week in 1581 and priest-harbouring became a treasonous offence.

Despite this context, and having been implicated by association with the Throckmorton Plot to assassinate the Queen in 1583, William Byrd was still working in the year of the Armada, publishing his commercial offering of consort songs, Psalms, Sonnets and Songs of Sadness and Pietie. The Musica Transalpina, an Anglicised collection of Italian secular polyphonic vocal chamber music, also appeared that year and marked the advent of the English Madrigal School, a movement highly influenced by the works of Tallis and Byrd, and which became the pinnacle of Elizabethan musical creativity, foreshadowing the baroque.

With the coming of the age of Shakespeare, secular music found a place to thrive. Theatre impresario and founder of the Rose, Philip Henslowe, would record in his diary that his company owned ‘trumpets and a drum, and a treble viol, a bass viol, a bandore, a cithern’, and the Globe, built in 1599, had a dedicated musicians gallery. Member of the English Madrigal School and one-time pupil of William Byrd, Thomas Morley, set It was a lover and his lass from As You Like It, with its very pop nonsense lyrics (‘With a hey, and a ho, and a hey nonino’, ‘When birds do sing, hey ding a ding, ding’) to music, and although it is the only contemporary musical setting for Shakespearean verse to come down to us today, it indicates the vibrancy of secular music at the time.

The popularity of Greensleeves continued unabated, mentioned no less than three times in The Merry Wives of Windsor, written in 1597. While this was the English Renaissance coming to fruition, it was at the beginning of the previous decade that English music had first exploded with a creativity on a scale never before seen in that then- tranquil country.