CHARLIE CONNELLY on the highlights of a highly unusual literary year… and some horrors lying ahead in 2021.

It feels a little bit weird looking back at 2020. Not least because it never really felt like a proper year, more as if we got stuck in a really long week in mid-March and never made it to the weekend. It is finally just about behind us but there’s a good chance we’re now somewhere between frying pan and fire as we embark on the fresh hell that is a post-Brexit 2021. But let’s not be too downbeat. Instead, here’s a look back at some of 2020’s more uplifting literary moments, avoiding the scandals, scraps, egos, whinges, open letters and dudgeons high and low to focus on the more agreeable things emanating from the literary year just passed.

For booklovers, one highlight was the ability to scope out the shelves of public figures when they appeared on television from their homes. Few things are more appealing to a bookworm than scanning other people’s bookcases and 2020 allowed us an unprecedented hootenanny of literary voyeurism. Bookshelves are where intimacy and exhibition mingle: yes, you’re displaying your literary taste but it’s in the privacy of your home. Until, that is, your home is beamed live around the world and it’s open season on your Jackie Collins paperbacks.

Most authors, of course, looked for their own books first. It sometimes meant going on all fours and crawling slowly towards the set like a leopard stalking an antelope: I guarantee there wasn’t an author’s television in the country in 2020 that didn’t have little nose prints all over the screen by the end of the year.

The sheer variety of bookshelf arrangements on view was impressive. Some were regimented and neat, others looked like the premises had just been subject to a comprehensive and eagerly executed search warrant. Some were well-organised, Nicola Sturgeon’s impressive collection of Scottish crime thrillers was filed alphabetically by author, others were over-organised, with some weirdos even arranging their books by colour.

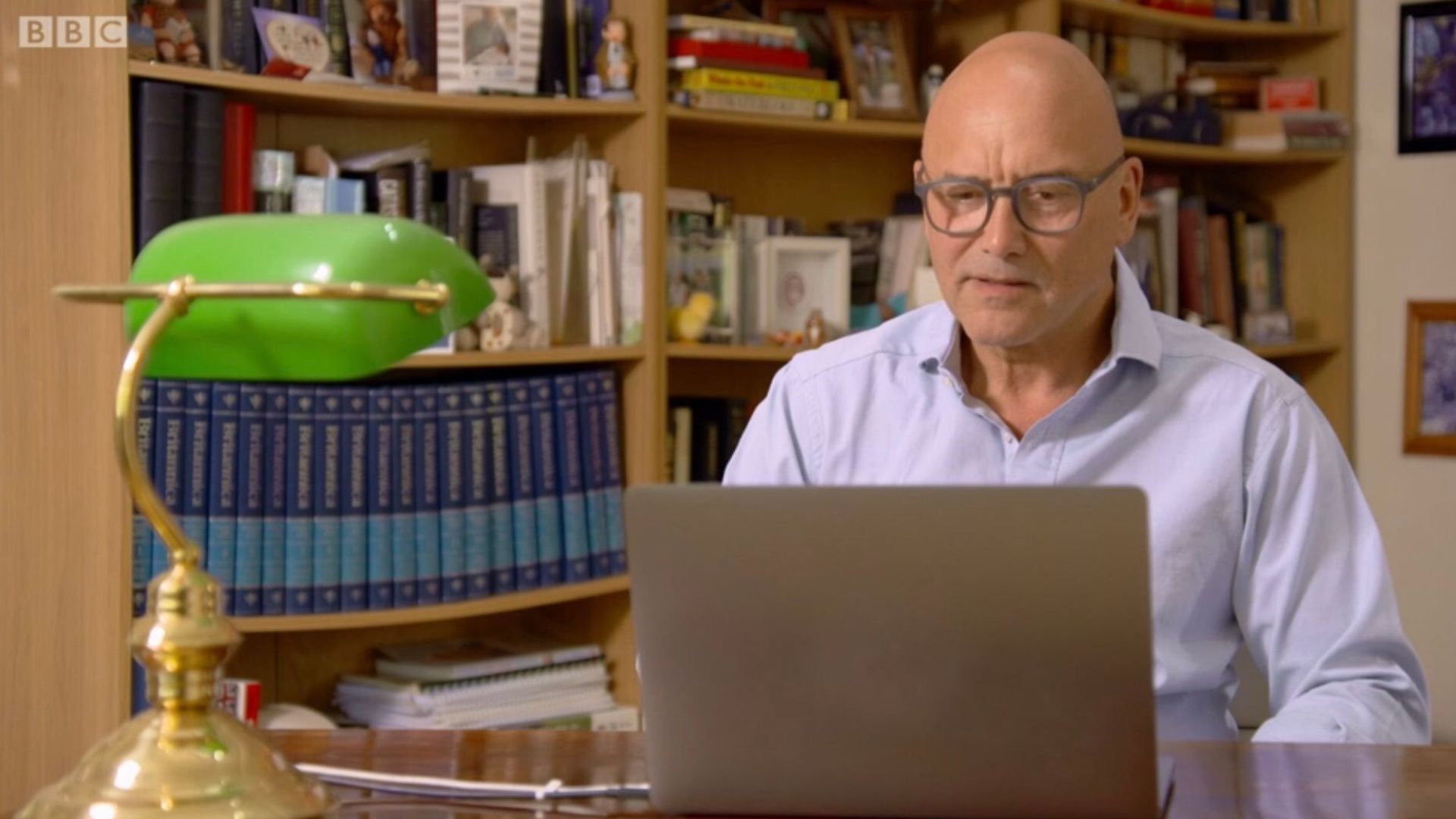

Occasionally the books eclipsed whatever the person was contributing to the national debate. In May there was great concern for a shelf seen behind professional cutlery-user Gregg Wallace that was visibly sagging beneath the weight of a set of encyclopaedias and appeared in danger of giving way at any moment. In September US constitution expert Ilya Shapiro took self-promotion to a whole new level when he appeared on BBC News having placed no less than nine copies of his own book, face out, on the shelves behind him, carefully arranged around his head and shoulders like a shimmering halo in a Byzantine church fresco.

Less aware of his backdrop was Boris Johnson when in August he addressed the nation from a school library in Leicestershire to much sniggering; the prime minister apparently unaware that displayed prominently on the shelves behind him were copies of The Twits, Betrayed, Resistance and Exodus.

The best bookish background moment of all came in March when foreign secretary Dominic Raab appeared on the BBC from his home, seated in front of a shuttered window. There were no bookshelves in sight but behind him on the windowsill, in two small piles, one at each shoulder, were nine books placed carefully with their spines in shot. Given that when he was Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union Raab admitted to not having managed to struggle through the daunting 35 pages of the Good Friday Agreement it’s fair to assume that he isn’t a big reader.

Maybe that’s why the books, which included Ronald Reagan’s diaries, a book about King Hussein of Jordan and an economics textbook, all appeared pristine and unopened. Still, when he finally finishes the GFA he’ll be a very well-informed Foreign Secretary indeed once he gets stuck into that lot. It’s practically an Amazon wishlist called ‘how to look like a well-read cabinet minister without really trying. Or reading’.

Maybe I’m doing Raab a disservice. Maybe he’d just had some kind of literary epiphany and this was the start of a serious bibliophilic road to enlightenment and self-improvement. Maybe soon he’ll even have enough books to justify a bookcase.

Elsewhere the June toppling of the Edward Colston statue in Bristol caused predictable sections of the comment media to go absolutely tonto. It was a little alarming to discover that these people apparently learn their history solely from public monuments and hence the de-plinthing of one of Britain’s most notorious human traffickers was somehow an attempt at ‘erasing’ history. Never mind books, never mind decades of academic research, never mind the internet, dropping Colston on his hollow metal bonce in Bristol harbour was an obliteration of knowledge itself.

This led to an outbreak of statue guarding by tough guys across the country. Tearing themselves away from World of Warcraft they paused only to whip their camouflage jackets from their banisters and tell their mums they might be late in for their tea as they bravely headed for market squares to line up, arms-folded, around statues facing imminent destruction from slavering hordes of history erasers.

The pick of the bunch was undoubtedly the band of gallant Nuneatonians who surrounded the statue of novelist and noted anti-slaver George Eliot in the centre of the Warwickshire town. With a Black Lives Matter event taking place just a couple of postcodes away these brave lads were determined there would be no transition from protest march to Middlemarch. Silas Marner wasn’t about become silenced Marner, amirite? Not on their watch. Not outside Nuneaton Debenhams. Thank you for your service, diligent brass novelist sentries.

2020 was a good year for found books. In early June Donald Trump was so pleased to have found a bible he strode out into a Washington ablaze with protests, crossed a road and held it out, upside down and back to front, for all to see. Closer to home, in 2008 a Buckinghamshire teacher had watched as a crate of perfectly good books was emptied into a skip while her school tidied up ahead of an Ofsted inspection. Thinking it a terrible waste she fished them out, took them home, put them in her loft and thought no more about it. One was a hardback first edition of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, of which only 500 copies were printed. In May 2020 it sold at auction for £33,000, possibly to Dominic Raab.

September brought news that 200 rare books worth £2.5million stolen in an audacious raid on a warehouse in Feltham, Middlesex, had turned up under the floor of a house in a remote part of Romania. The gang was arrested and the books, which included rare editions of Galileo, Isaac Newton and an extremely rare 1566 edition of De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium by Nicolaus Copernicus were recovered undamaged and returned to their anxious owners.

The literary awards season adapted successfully to the pandemic but one 2020 bunfight that didn’t take place was the Bad Sex in Fiction award organised by the Literary Review, which rewards or condemns, whichever way you choose to, erm, take it, the most badly realised account of a sexual act in the year’s fiction. The judges felt 2020 was miserable enough without adding to people’s woes by inflicting adverb-heavy, overwrought nookie upon them as well.

An award that did go ahead was Oddest Title of the Year prize, which has since 1978 celebrated the year’s weirdest literary nomenclature. The 2020 gong went to Dogs Pissing at the Edge of a Path by Gregory Forth, an academic study of the use of metaphor by the Nage people of Flores and Timor that pipped Introducing the Medieval Ass and Lawnmowers: An Illustrated History to the prize.

Two aspects of the publishing industry deserve particular praise for how they handled the challenges of 2020. First, the bookshops themselves, who worked especially hard to keep their businesses alive while keeping people supplied with books without propelling yet more solid gold charabancs filled with doubloons towards Jeff Bezos. Websites were hastily built or updated to enable a click-and-collect service while some shops even offered home delivery, quite often by bicycle. Imaginative and innovative in the face of crippling restrictions, these bookshops absolutely excelled themselves.

Publicists, often unsung, always underappreciated, also faced their toughest year yet. The amount of books being published is increasing just as the amount of literary space in newspapers and magazines is reducing, even before the pandemic. Book publicity also relies heavily on events, from small scale readings in the corners of bookshops to giant, sprawling literary festivals. There was none of that in 2020 but publicists, in cooperation with festival organisers and authors, adapted accordingly and took as much as they could online with a considerable degree of success. Physical launches that might pull in 50 or 60 people, a sizable chunk of whom would be related to the author and a further proportion just there for free wine, became streaming events that drew five times that number, attracting people who were genuinely interested enough to tune in and even supply their own booze.

Add to that an 80-year-old Margaret Atwood being spotted pre-pandemic riding an electric scooter around a New Zealand car park and there were quite a few bookish reasons to be cheerful in 2020. What will 2021 bring? Maybe one of the last significant publishing news stories of 2020 provides a hint. The literary year ended with Little, Brown cancelling Julie Burchill’s forthcoming Welcome to the Woke Trials: How #Identity Killed Progressive Politics just four months before its publication date.

The publisher pulled the plug saying Burchill’s comments about Islam, in an online exchange with journalist and activist Ash Sarkar, had “crossed a line with regard to race and religion”. Sound move though it may be by the publisher, there are still advantages for both sides. Little, Brown takes an important and noble stand while Burchill can say legitimately that she was cancelled while being free to shop her book around other publishers.

The timing is the issue here, though. Having been slated originally to appear at the start of April, Burchill’s book risks being gazumped by a growing list of forthcoming tomes written by the kind of sensitive soul who interprets people disagreeing with them as a direct attack on their free speech and uses their national newspaper column to complain about being silenced. But hey, let’s stay positive, these books will be easy to spot and avoid. The titles or subtitles will contain the word ‘woke’, there will probably be an ironic hashtag in there somewhere and the cover will feature a photograph of the author looking cross.

That all lies ahead, though. Let’s end with the story that perhaps sums up Britain’s literary 2020 best of all: how the second person in the country to be vaccinated against Covid-19 was William Shakespeare of Warwickshire. He was in Coventry Hospital at the time so there were no bookshelves visible behind him in the pictures, just a sign saying “please leave windows closed”. Apparently Dominic Raab’s reading it but hasn’t finished it yet.

FIVE GREAT BOOKS ABOUT FRESH STARTS

LIFE AFTER LIFE

Kate Atkinson (Black Swan, £8.99)

A brilliantly innovative novel that deservedly won the Costa Novel Award in 2013, Life After Life is a book entirely comprising new starts. Ursula Todd is born during a snowstorm in 1910, over and over again. At first she dies before taking a breath, but as the book progresses she lives longer every time in a novel that asks what you would do if you had the chance to live your life all over again.

THE THING AROUND YOUR NECK

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Fourth Estate, £8.99)

A dozen brilliant short stories from one of the world’s greatest living novelists, each one a tale of change, either forced upon the protagonist or a chosen journey of self-determination. Her Half of a Yellow Sun was declared the ‘best of the best’ among the winners of the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2020, and this collection from 2009 is up there with her best work.

ELEANOR OLIPHANT IS COMPLETELY FINE

Gail Honeyman (HarperCollins, £8.99)

With two-and-a-half million copies sold since its publication in 2017 Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine is one of the literary sensations of the last decade. Honeyman’s story is of a 29-year-old Glaswegian accounts clerk whose timid life is changed when at a rock concert she decides the singer in the band is the love of her life. A deeply moving novel of personal redemption.

JANE EYRE

Charlotte Bronte (Penguin Classics, £5.99)

A novel of fresh starts, the desire for them and the opportunity to make them, for the eponymous Jane and Mr Rochester. As Jane seeks her independence after a challenging upbringing, falling in love with Rochester brings its own challenges, not least that he has his own alarming secret from which he seeks release for a brighter future.

WHERE THE CRAWDADS SING

Delia Owens (Corsair, £8.99)

Set in North Carolina in 1969, Owen’s worldwide bestseller tells the story of Kya Clark, who lives alone out in the wild and is known locally as the ‘Marsh Girl’. A murder and its aftermath forces Kya into the latest of many new starts in her life, with consequences that resonate far beyond the natural world in which she lives.