For 70 years, the European Union, and its previous incarnations, has been an undeniable force for peace

Since the Second World War, with countries opting to work together to resolve differences, tensions between peoples and nations have reduced. Other organisations, such as NATO, can also claim credit for this. And the peace has not always held, with some notable and tragic failures over the past 70 years. But the EU’s role has been immense. Here are some of the ways it has tried, though not always succeeded, in bringing peace.

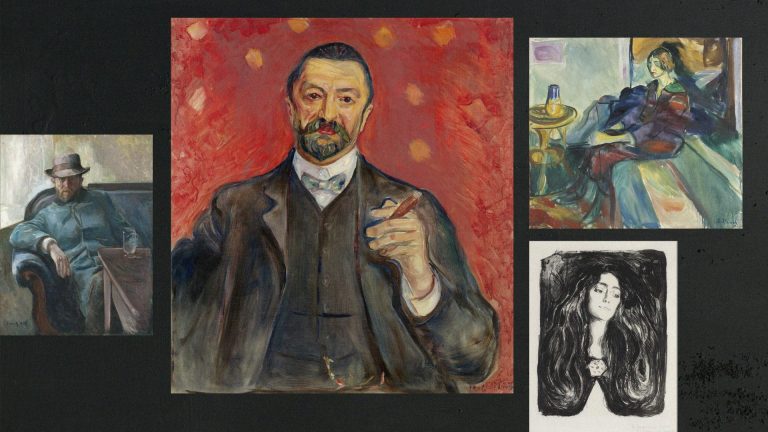

Pax Europaea

Most fundamentally – and for this reason often overlooked – the EU has contributed to seven decades of almost uninterrupted peace in a continent which, in the previous 50 years had spawned the two most destructive conflicts in history. The EU, or at its predecessors, was established specifically to counter this. In binding nations together in mutually beneficial trading arrangements, economic, if not geographical borders, were blurred and the incentive for using war to achieve power and wealth has been removed. In 2012, the EU institutions were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of this, prompting much mockery from eurosceptics, who seemed to wilfully misinterpret what it was for.

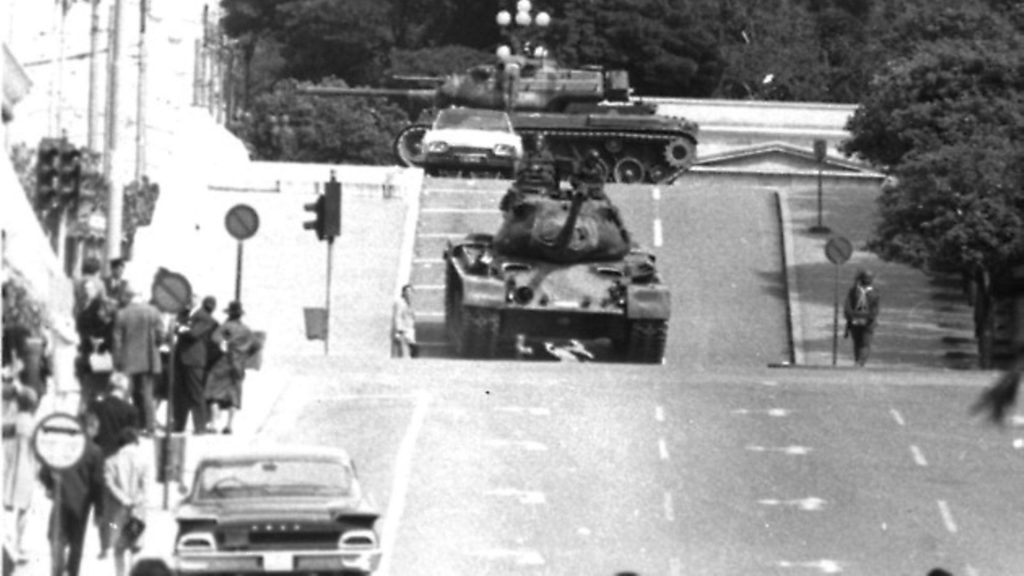

Fall of the Iron Curtain

The collapse of the Communist Bloc and the succession of revolutions that took place across central and eastern Europe took place with remarkably little bloodshed. Again, a major factor in this was the European Union, providing support and guidance to countries in their transition to democracy and market ecomonics. The modernisation of these countries was achieved through integration with the EU

Ukraine

The war in Ukraine is one of the biggest stains on European diplomacy since the Second World War. Indeed, it has become a handy stick with which critics (Boris Johnson included) can hit the EU, blaming it for starting off the chain reaction that led to the conflict. The argument goes that the EU’s overtures to Ukraine about closer ties were too provocative for neighbour Russia to ignore. However, while the EU may have been wrong-footed, it cannot be held responsible for Moscow’s violent response.

Spain and Portugal

Peace and stability in Spain was far from guaranteed following the death of Franco in 1975. But it was achieved, in large part, in its transformation into a parliamentary democracy, by its aspiration to join the European Community. Spanish accession had not been possible during his dictatorship, but one of the first significant acts of the country’s first democratically elected government for more than 40 years was to present a formal application to join. The implementation of democratic policies allowed relations between Spain and Brussels to improve and the country joined the Council of Europe in November 1977, and the EC in 1986.

Portugal followed a similar, peaceful trajectory from relatively recent dictatorship to social democracy and membership of the EU. Its first democratic elections in 50 years were held in 1976. Ten years later, it joined the EC, with Spain.

Former Yugoslavia

The failure to prevent genocide being carried out on European soil is an undoubted black mark on the EU. European reluctance to support a military intervention with clear political goals proved to be the main obstacle to halting the bloodshed in Bosnia. The EC, as it then was, did not do enough to punish the Serbs for breaking ceasefire agreements and not meeting commitments, encouraging them to continue. Even before then, squabbles between European capitals over how to deal with the fragmentation of Yugoslavia helped to cast the die. That said, European leaders were not alone in major diplomatic failures, and can hardly be blamed for the break-up of Yugoslavia itself. Since the violence, the EU has encouraged the gradual integration of the former constituent parts into the union. In 2013, Croatia became the to join, and Montenegro, Serbia and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia are official candidates. Accession negotiations have also been opened with Montenegro and Serbia. Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo are potential candidate countries.

Ireland

It is not doing down the contributions of others to highlight the role played by the EU in helping to bring peace to Northern Ireland. Brussels has been providing millions of pounds worth of financial support to peace initiatives in the region since 1989, almost a decade before the Good Friday Agreement. But its role in transforming relations between Britain and Ireland goes back even further, to when the two countries both joined, in 1973. Bilateral relations between London and Dublin greatly improved in the multilateral setting provided by the EU, enabling the two to work increasingly together in the cause of peace. Membership also helped connect the economies of the north and south of Ireland, bringing a single market and an open border.

Cyprus

The island has been divided since the Turkish invasion in 1974, but the EU is now playing a key role in attempting to find a resolution. When the Republic of Cyprus joined the Union in 2004, all Cypriots, whether living in the north of south, became EU citizens, and the event was marked by Turkish Cypriot rallies in support of peace and the EU. Membership injected momentum into the peace talks on the island, with many in the north attracted by the benefits. Efforts might have stalled somewhat, not helped by the eurozone crisis and events in Turkey, but the EU, working alongside Turkey, still offers to best framework to achieve peace and reconciliation between the two communities.

Greece

Yet another major European country which, in recent decades, has emerged, relatively smoothly, from authoritarian government to become a functioning – if still deeply troubled – democracy. Greece was governed by a military junta until 1974. Six years later, once democracy had been restored, it had joined the European Community. Its application was initially resisted by some, for economic reasons and national concerns. But strategic concerns won out: Greece was admitted as a way to ensure stability and democracy in southern Europe, at the height of the Cold War. It worked, and Greece provided a model for Spain and Portugal to follow, five years later. The country still faces complex economic problems and an uncertain future, but has come a long way from the civil war and military dictatorship it has endured in the last 70 years.