This piece was updated to reflect the 35th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall

On June 12, 1989, Michael Ebert packed a small suitcase into the boot of his Trabant. He was about to visit his cousin in Bonn for the first time since 1960. He couldn’t drive westwards from his home town of Furstenwalde because of the wall dividing Berlin. Even if he drove around the city he would eventually come up against the fence that partitioned his nation, the German Democratic Republic (or DDR) in the east, from his cousin’s, the Federal Republic of Germany (or FDR) in the west.

So he headed south east, crossing into what was then Czechoslovakia and right on into Hungary. Ebert, an agricultural vehicle mechanic, paused in Hungary at a roadside buffet to eat lángos, the deep-fried bread he’d acquired a taste for while an exchange student in Eger in the north of the country. Hungary had been well known among the Eastern bloc of communist nations for its higher standard of living, leading to the policies of its government being declared ‘goulash socialism’. Ebert had taken full advantage.

Back in his car he headed for the border with Austria. He was astounded to find a short queue of Trabants and Skodas all with DDR number plates. But although the guards were cursorily checking papers, they waved him through. He turned north, heading through Austria and up towards Bonn, arriving around 10pm the next day.

His cousin was thrilled to see him, the family fed him and they drank beer into the small hours. And in the flat Ebert saw things that he knew existed in the east but people rarely had in their homes in Furstenwalde – a telephone, a fridge, a SodaStream. But the item the then 47-year-old was most fascinated by was the television. He had one at home, of course, but this had a box with buttons you pressed. You didn’t have to leave your seat to change channel. And another box contained VHS tapes to record TV programmes.

He stayed up all night switching between channels and watching the news programmes that explained to him for the first time what was happening in the DDR, and why quite unexpectedly he’d had the opportunity to travel to the West. It was at that point – “about three in the morning,” says Ebert – that he realised what would become dramatically clear to the world just four months later – 30 years ago this autumn – that the Berlin Wall had become redundant.

After the western Allies and the Soviet Union had carved up Germany following the end of the Second World War, Berlin had become an outlier, a special case. Although wholly within the Soviet sector of Germany which eventually morphed into the communist DDR, it too had been subdivided into four sectors, meaning that an enclave of the FDR remained within East German territory. And by the early 1960s the lure of the West’s freedoms and commercialism was proving too much for the tiring East German population.

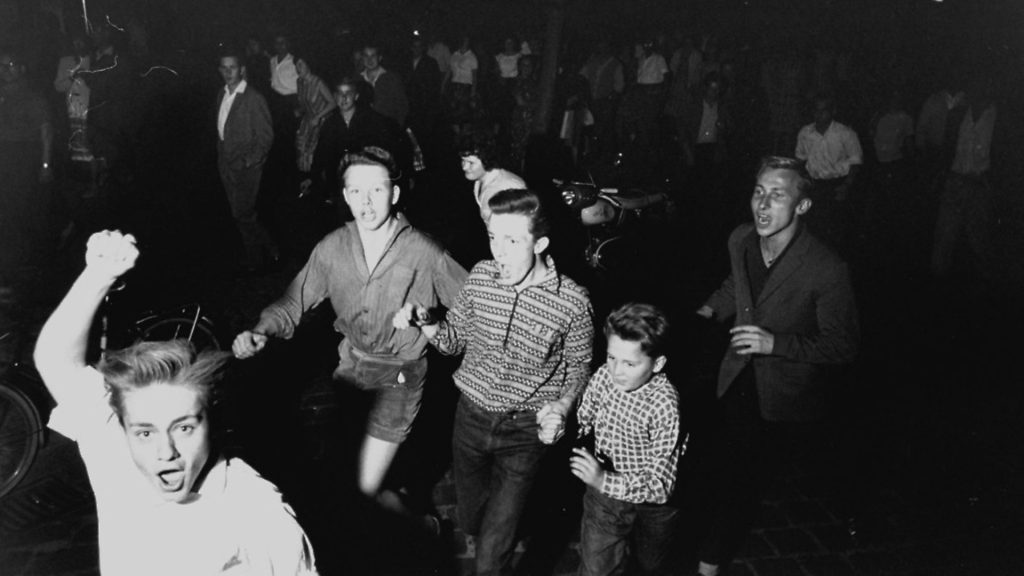

Between 1949 and 1961 as many as three million East Germans had fled west. That was almost 20% of the entire population. And in Berlin, defecting was as simple as walking down the street. The East German authorities needed to stop their population haemorrhage… so they built a wall.

Michael Ebert is now retired and lives in Leipzig with his daughter and extended family. He was a teenager living outside Berlin when the wall was built and tells me that his memories of its earliest days are hazy. “I remember it going up,” he recalls, “although news was a bit sparse and obviously controlled by the government.”

However, he puts me in touch with his great uncle Volker Baumann, now 89, who was living in the city at the time the wall suddenly appeared. “After the war ended we all knew which sector of the city we lived in,” he recalls. “But travelling between sectors for work or to visit family and friends was relatively simple. Berlin still had a unified city council despite being divided into four.

“Some houses, like my former schoolfriend’s had one door in the Soviet sector, the other in the American sector. Most of the time we just walked straight through. Then, overnight, everything changed.”

Construction of the wall began on August 13, 1961, and over the next few weeks the barrier got higher and the gaps between it smaller. Simultaneously, to the west, the East German border with West Germany was also being fortified and fenced. By the time the wall itself was complete it was, at its highest point, 4.2 metres and, with the fencing used in some sections, more than 140 kilometres long, surrounding West Berlin entirely. Where buildings blocked its path they were either bricked up or demolished – entire streets were severed, neighbours could no longer talk to their friends next door.

It looked impregnable (and pretty much was) but it was a simple design – concrete blocks topped off by a horizontal empty concrete water pipe to make climbing it difficult. The land in front of it on the East German side was cleared the following year to create what would become known as the death strip.

Illuminated, guarded by more than 300 armed watchtowers and covered in trip wires, anybody attempting to cross was shot. But still they tried, often in full view of camera crews on the western side. It all led to the reels tragic footage of people like 18-year-old Peter Fechter, the 27th person to die at the wall, who bled to death at its foot on August 17, 1962, in full view of the watching western media and public.

The East Germans border guards probably left him lying there as a message to their people, but western officials were culpable too, scared – diplomatically and personally – to attempt to reach him. His screams were to haunt those who were there and it took him an hour to die. A memorial to him now stands at the spot. Estimates vary as to how many other people died in the death strip but some place the total above 200.

There were many daring escapes too — as many as 5,000 people fled over, under or through the wall, although it is suggested that as many as 100,000 tried.

The first was by East German border guard Conrad Schumann who jumped over barbed wire on Bernauerstrasse as the wall was being constructed. You can buy postcards in Berlin of his leap, captured by a photographer. In the fictional 1967 Michael Caine movie Funeral in Berlin, an East German worker escapes in a metal bucket lowered over the wall by a crane in West Berlin, but the reality was often just as audacious.

Thomas Krüger flew his light aircraft to RAF Gatow in West Berlin. The British airmen sent his dismantled plane back to the east daubed with messages such as “wish you were here”. Another escapee approached the barrier in a convertible car with the windscreen removed and picked his moment to speed under the barrier. In May 1962, 12 elderly people dug what became known as the Senior Citizens’ Tunnel as they burrowed 32 metres under the wall.

Friends Michael Becker and Holger Bethke fired an arrow carrying a rope from the top of a five-storey building in East Berlin and zip-wired across to the West. Tightropes, hot-air balloons and even a tank were all used successfully.

One of the most amusing escapes came when a would-be defector broke into the train tunnels of the U-Bahn and headed for a station on the western side. The U-Bahn had continued to circulate under East Berlin despite its stations being bricked up. A guard was sent to apprehend him, but hours later had not returned so a second guard was despatched. He too did not return. Only when a third guard (this time with a chaperone) investigated did it become clear the original fugitive and his two pursuers had all defected to the West.

West Berliners were active in helping their fellow citizens from the East escape with students from the Free University of West Berlin organising the Unternehmen Reisebüro (or Corporate Travel Agency). Activist students Detlef Girrmann and Dieter Thieme coordinated a network that ensured thousands got out.

The DDR called the wall the ‘anti-fascist protection rampart’ although no ‘western fascist’ was ever recorded as killed crossing to the east.

Coloured a totalitarian white on the eastern side, with anarchic freeform graffiti on the west, it is said that because the wall was built slightly but entirely on East German territory the West Berlin authorities were unable to clean up the slogans and political symbols on their side. Presumably, however, it also served their purposes not to do so as it contrasted starkly with the illuminated, barbed-wire death strip on the other side.

You could, in some circumstances, cross from the East legally. But it wasn’t easy. Anybody claiming the state old-age pension could travel freely to the West (the DDR considered they had little economic worth) and some professions had permission to travel: musicians or people exporting goods. Otherwise you were at the mercy of the passport authorities. Even exceptional circumstances, such as a dying relative in the West, wouldn’t necessarily guarantee you permission to travel.

The wall was the ultimate symbol of the Cold War, tacit evidence of the Iron Curtain Winston Churchill had predicted would descend on Europe after the Second World War. It seemed a permanent reminder of the division of the continent.

So its fall, 30 years ago this autumn, to those who were there or witnessed it on television around the world, seemed as rapid as it was inconceivable. Yet the origins of its demise could be traced back many years.

As a PR exercise it was, of course, a total failure. To be fair, it was never meant to show the world how caring communism could be, but the death toll and the sheer symbolism of autocracy that it engendered in its 140-kilometre length had no equal anywhere in the world.

As a microcosm of ‘right’ versus ‘wrong’ (whatever one’s world view) its removal, in hindsight, was always a matter of when not if. In 1987, in a speech near the Brandenburg Gate, United States president Ronald Reagan demanded that Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev should “tear down this wall”. The truth was that by then it was already crumbling metaphorically, if not figuratively.

By 1989 dissent towards the communist regimes of Eastern Europe was becoming more overt. The rise of the anti-government trade union Solidarity in Poland inspired people in other Eastern bloc nations to express their opposition. Some governments responded with force, some with indifference while others took a more pragmatic approach.

In May, after weeks of protest and the rise of numerous parties opposed to communist rule, the Hungarian government opened its border with Austria. Prime minister Miklós Németh had realised only democracy and a freer economy could prevent his government’s collapse. But one key political development had spurred Nemeth on – one well noted by the growing numbers of protestors throughout the east and one greater even than the rise of Poland’s Solidarity movement. It was, in hindsight, the pivotal moment in the fall of eastern European communism.

Mikhail Gorbachev had become general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1985. He realised that the USSR was undergoing serious and permanent economic decline after years of stagnation under hardline leaderships.

He also realised that there was only one solution: a total reconstruction of the Soviet economy (known as perestroika) and liberalisation of Soviet society (known as glasnost, or ‘openness’). Even more significantly for the people of the Soviet Union’s satellite nations he effectively apologised for his nation’s invasions of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, renouncing what had become known as the Brezhnev Doctrine which had advocated Soviet military intervention in satellite states if deemed necessary.

Soviet interference in the affairs of the other communist nations of Eastern Europe was over – the political and economic costs were too great. The Red Army’s presence in eastern Europe was a huge strain on the Soviet Union’s moribund economy especially considering that until 1989 it was fighting a resource-sapping, 10-year war in Afghanistan.

However, Gorbachev merely wanted to restructure and liberalise communism, not bring about its downfall, but the people of eastern Europe were also aware that their voices could now be heard. Without the tacit reassurance that the repudiation of the Brezhnev Doctrine brought about, it is almost certain that Hungary would not have had the courage to open its border to the west. That it did caused a chain reaction…

Now there was a way out, even for the embattled citizens of East Germany. People like Michael Ebert got into their Trabants and drove south, crossing into Austria. And if Erich Honecker, East Germany’s leader, believed he could contain his people any longer, or if he was relying on the Soviet Union to intervene, he was mistaken.

By October 1989, more than 30,000 East Germans had fled. Michael Ebert had returned home, but others stayed. Honecker was panicking. On October 3 he closed the entire border of his country, demonstrators were beaten and imprisoned, and a shoot to kill order issued to the military.

But it was like trying to stop a volcano erupting by throwing a glass of water at it. Honecker’s troops refused to shoot on their compatriots and Soviet soldiers stationed in East Germany were ordered by Gorbachev not to leave their barracks.

Honecker was ousted, the Czech border reopened and East Germans began to leave again. And after half a million East Germans collected in Alexanderplatz near the Berlin Wall, the East German authorities realised they could no longer stem the flow.

On November 9, the border with the west was opened. Since its construction, around 200 East Germans had been shot attempting to cross it, but now guards were unwilling to start firing at the thousands of people pushing their way towards the gates.

People cheered as others began to tear down parts of the wall with sledgehammers and bare hands in astonishing scenes beamed around the world. Dissident writer Stefan Heym described the feeling as “if windows had been pushed open and fresh air was coming in”.

Gerhard Schumann was a student in Potsdam. A friend called him up when he heard what was happening at the wall. They took a tram into the city. “I never thought it would happen,” says Schumann. “Never. My grandparents were over 65 and had visited family in the West. But I couldn’t get permission. It was all too difficult, but suddenly there it was, falling before my eyes. People were shouting “Tor auf” (“open the gate”). When the guards did there were cheers and a surge in the crowd and a sense of ‘OK, you can’t stop this now’. It was the most exhilarating thing.”

One year later, on October 3, 1990, Germany was finally reunified. It had been opposed both from the right in the West – British prime minister Margaret Thatcher was concerned that a unified nation would dominate the European Community (the forerunner to the EU) – and from the left in the East – Gorbachev (correctly) feared it would lead to the collapse of Soviet hegemony and threaten the existence of communism in his own nation. But their opinions no longer counted once formerly disenfranchised citizens such as Michael Ebert had acted.

The wall had been a physical and ideological divide, but it was also a psychological one too. It symbolised what people couldn’t do, a denial of so many opportunities, especially for post-war reconciliation, all of which were put on hold for more than four decades.

When it was toppled a nation, and most of Europe, breathed out. “I often wondered what was on the other side, says Monika Neu, who was a 16-year-old schoolgirl in East Berlin in 1989. “I wanted to find out.” “So did I,” says Ursula Müller, 18 at the time, who lived in West Berlin. “Can you imagine how strange it was for us living in our small island city?” she says.

“But it’s all we were used to, then suddenly there was a hole in the wall, but the hole in the wall helped fill a hole in my life, and Monika’s. She is now my best friend. We met in the week after the wall came down on the Kurfürstendamm [West Berlin’s main shopping street].”

“I was buying a skirt,” says Neu. “It seemed so much more fashionable in the West and my dad had some West German Deutschmarks and told me to buy the skirt. So I did, and I met Ursula working in the store. I’m so happy the wall came down.”

The two women are a microcosm of German reunification, symbolic of what was denied to so many people for so long.

As they chat in a cafe, where I meet them, we are sitting probably a mere 80 metres from where the death strip ran only 30 years ago.

Yet their friendship amid the multicultural, tolerant city of Berlin in 2019 makes it seem like it was a million miles away.