The Ponte delle Tette in Venice (the clue is in the name), sits between the sestrieri of San Polo and Santa Croce. Here, in the 15th century, bare-breasted sex workers lined the bridge advertising their services, and according to some reports were even paid by the state to do so in a ludicrously vain attempt to lure men away from homosexual liaisons in the city.

It’s an obvious point to state that six centuries later, female breasts continue to symbolise universal ideas of sex, titillation, and primal male desire.

But a short walk from the Ponte delle Tette in Venice, one can find more bare breasts on public display in a radically different context. The Madonna Lactans (Nursing Madonna) is a relief sculpture on a building, showing the Virgin Mary breastfeeding the infant Jesus. It is as ubiquitous a symbol of virtuous Christianity as bare female breasts are a signpost for sex and male desire.

This complex and varied symbolism of the female breast is broadly surveyed this summer in Breasts, an exhibition at the ACP Palazzo Franchetti in Venice, which runs alongside the 60th edition of the International Art Biennale. Visitors enter down a corridor swathed in flesh-toned folds of fabric that is part theatrical bordello, part lingerie changing room (the exhibition is sponsored by Italian underwear brand Intimissimi, an on-the-nose collaboration that has allowed the exhibition to remain free of charge).

The first room situates the visibility of breasts within the history of art, the point of departure being a tiny 15th-century tempera on wood panel of a breastfeeding Virgin Mary, which provides the necessary central anchor to explore the long tradition of the archetype in western art, although it remains that only pre-modern piece in the whole show.

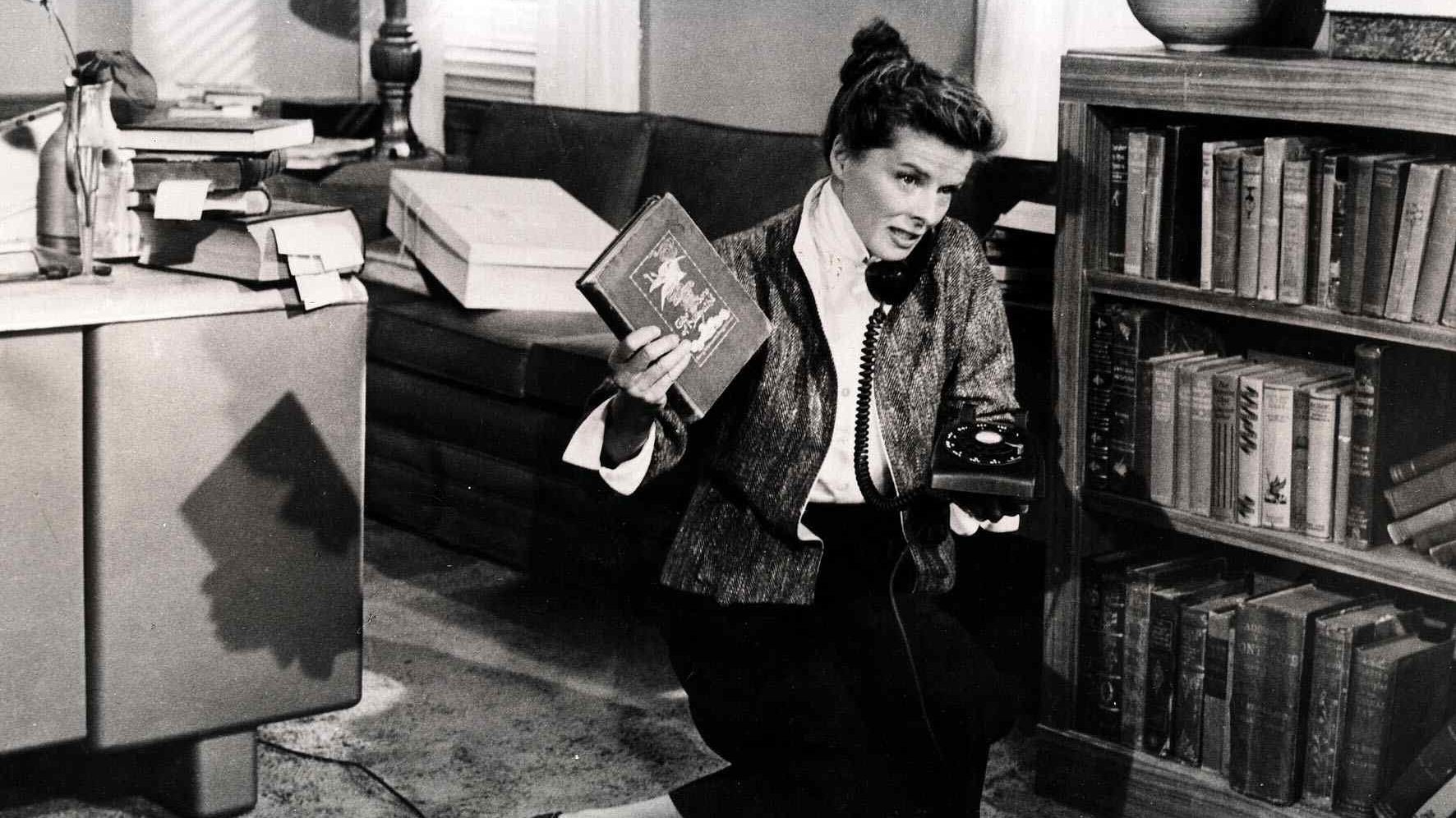

Elsewhere in the room, the theme is taken up in images by Cindy Sherman, and Canadian artist Anna Weyant, both of which riff on the omnipresent bare-breasted female body in European painting.

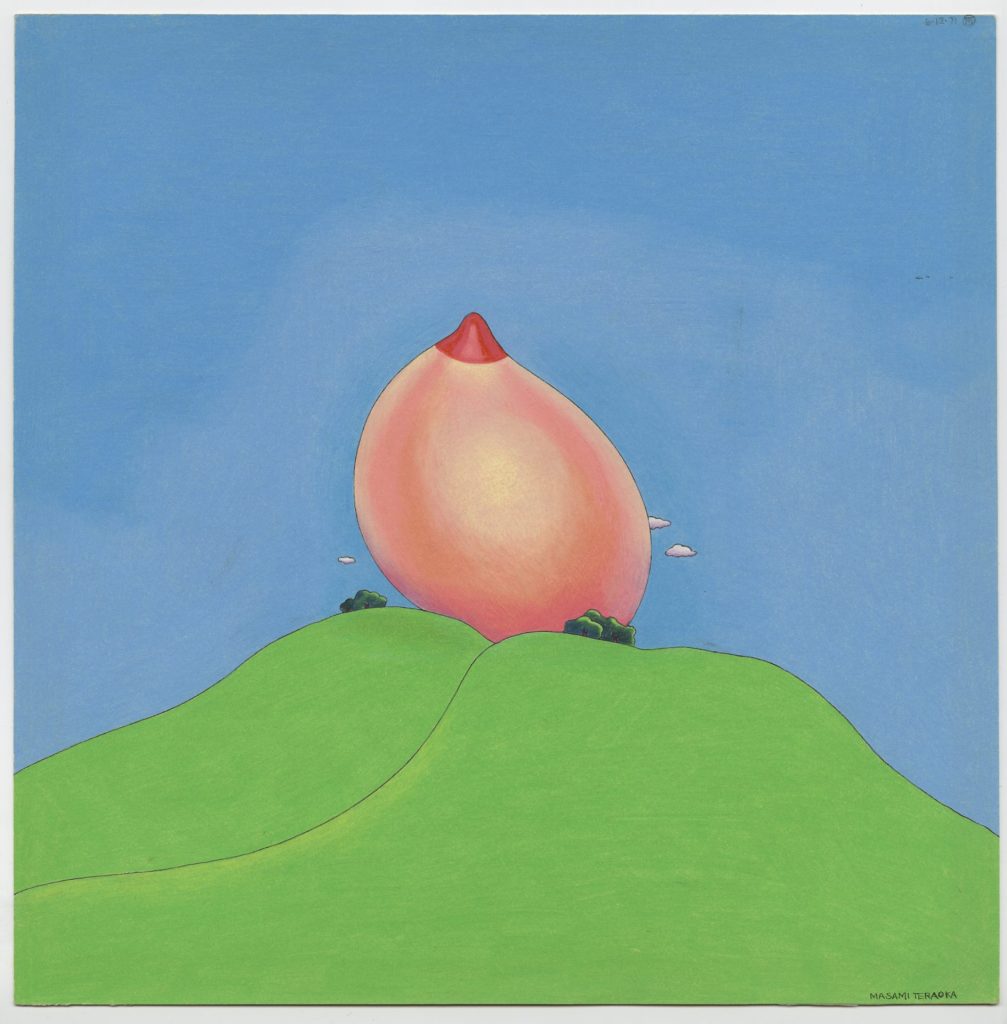

“The focus of the exhibition is to open a dialogue around themes such as motherhood, empowerment, sexuality, breastfeeding and breast cancer awareness,” says Carolina Pasti, the Milanese curator of the exhibition, who has assembled an assortment of household names and younger, emerging artists. (Alongside Sherman, the familiar names of Louise Bourgeois, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí and Giorgio de Chirico all feature).

Despite the poppy fuschia flush of the interior walls and marketing materials, Breasts doesn’t shy away from confronting the sobering issues of disease and mortality that are of as much significance as lust and breastfeeding when it comes to cultural understandings of this body part, despite being far less visible. (In the UK, breast cancer is the most likely cancer to affect women, and accounts for 32 deaths in the country every day.)

To underscore this commitment, a portion of catalogue sales profits are being donated to Italian medical research non-profit Fondazione IEO-MONZINO. Moreover, it’s a strong current that interconnects a number of objects and images in the exhibition.

“Breasts symbolise Eros and Thanatos – the embodiment of desire and nurturing, contrasted with illness and mortality,” says French artist Prune Nourry, who survived breast cancer aged 31, and used the experience as inspiration to inform her art practice.

Nourry’s contribution to the show is Oeil Nourricier (Nourishing Eye) a glossy, blown-glass orb topped with cast bronze nipple that resembles both breast and talismanic eye. The artist was inspired by the long tradition of producing votive sculptures found across multiple cultures, in which small representations of afflicted body parts are crafted for ritual ceremonies focused on the hope of healing and recovery.

In 2021, Nourry produced Aux Amazones, an artist book of images, testimonies and expert advice for confronting breast cancer, which was distributed for free to patients in hospitals in French-speaking countries. The title (For the Amazons, or Like the Amazons) refers to the Greek myth of the Amazon tribe of matriarchal warrior women who purportedly amputated a breast to better wield their weapons.

The theme of resilience and transformation is taken up in British artist Charlotte Colbert’s sculpture Mastectomy Mameria, a plaster sculpture that recalls the ancient fertility icon of the many-breasted Diana of Ephesus sculpture from the ancient Temple of Artemis in Turkey.

Here, Colbert envisages something of the life cycle of the human breast – some rendered in nubile, apple-like form, others distended and ballooning as a result of breastfeeding; or deflated, scarred and mutilated whether through surgery or the ravages of age.

The artist says: “Breasts are scary, erotic, nurturing, weird, compelling, sensual, afflicted, sore, delicious… they evolve, they change, they seep, they pleasure, they perk, they droop, they can be reinvented, they scar, they heal, they kill, they comfort.”

The slippery nature of the breast as a symbol that moves from one meaning to another is rendered in Mexican artist Aurora Pellizzi’s The Kiss, a small hand-felted fibre work that plays on the conundrum of visual perception known as Rubin’s Vase, an image which, depending on how it is looked at, appears simultaneously as a vase or two faces in profile.

In Pellizzi’s small, tactile felted image, the image of the vase flips with two candy-pink breasts about to touch, which made me think about the little cakes eaten in Catania to commemorate the Christian martyr Saint Agatha, the patron saint of breast cancer patients.

That the breast is most commonly depicted as a straightforwardly erotic emblem, most usually representative of male desire, is also given due space, whether in arch-misogynist British artist Allen Jones’s fetishised bondage mannequin, or French photographer Philippe Garner’s lovingly erotic photograph of his wife’s breast, bathed in the St Tropez sunlight.

But there are also occasions in which the male fascination with female breasts is sent up and satirised, such as in Canadian artist Chloe Wise’s wryly sleazy oil painting Soccer; a pair of anonymous, pendulous breasts resting on a football, which adds a note of levity in a show that aims to mobilise discussion of serious and profound concerns.

Erotic female agency and body positivity also find its expression in Italian artist Giovanna Ferrero Ventimiglia’s cast of her breast in bronze entitled Do Not Forget Me, a gift to a lover that puts any of the erotic gestures of Byron or Casanova to shame.

Indeed, one of the strengths of Breasts is that all perspectives are represented here and without judgment; from juvenile fascination with mammary glands, to the worshipful beauty of youthful bodies (including in fashion photography by Irving Penn and Lakin Ogunbanwo), as well as the mortal contemplation of the breast as an organ that nurtures life as well as bringing death through disease.

Breasts is a conversation starter couched in accessible terms, an experience that is not a given in the parade of contemporary art that swells Venice during the art Biennale. A lobby space near the start of the exhibition combines advertorial space for Intimissimi with a vitrine filled with silicone implants that can be taken out, touched and held. During my visit it became a space for conversation and exchange.

One woman told me about her sister’s decision to have a double mastectomy followed by implants because she carried the BRCA gene, while we pondered how that pound of fake flesh would sit in our own bodies, and what would drive that choice, whether it were motivated by health concerns or the desire to conform to ideas of physical beauty and power.

An unexpectedly moving highlight was watching French artist Laure Prouvost’s Four for See Beauties, a recent conceptual film by the former Turner Prize-winning artist that draws sensuous parallels between early infant life, and the pulsing, yearning bodies of marine and aquatic life that are also driven by suction and sensation.

In contrast to the docile, restrained Madonna Lactans of Christian imagery, Prouvost’s film presents breastfeeding as something transcendental, pleasurable, primordial and humblingly, reassuringly animal, as well as wildly erotic.

In a 21st century in which social media still censors female (but not male) nipples, when breastfeeding in public is regularly socially frowned upon, and topless bathing illegal in many parts of the world, Breasts offers a relevant revaluation of the cultural discourse around female bodies through art, one that could be easily overlooked by snobs who may disregard the content for what they see as gimmicky “clickbait”.

It is a life-affirming show that presents human breasts as majestic, desirable, comical, tender, erotic, diseased, crass and playful; characteristics that some might say are all shared by its host, the city of Venice itself.

Breasts is at ACP Palazzo Franchetti, Venice until November 2