Boris Johnson is a man who invites comparisons. Most of them are unflattering – he’s regularly compared to a circus clown or to a scarecrow, for example, and perhaps as a tin-eared man (though never a lion).

The man himself has a comparison he fervently – even desperately – wants us to make, and has even tried to help us towards it by writing a book extensively making that comparison himself. That is, of course, to Winston Churchill, but despite all of this helpful direction, it’s a comparison no one, even on his side, can even try to make with a straight face.

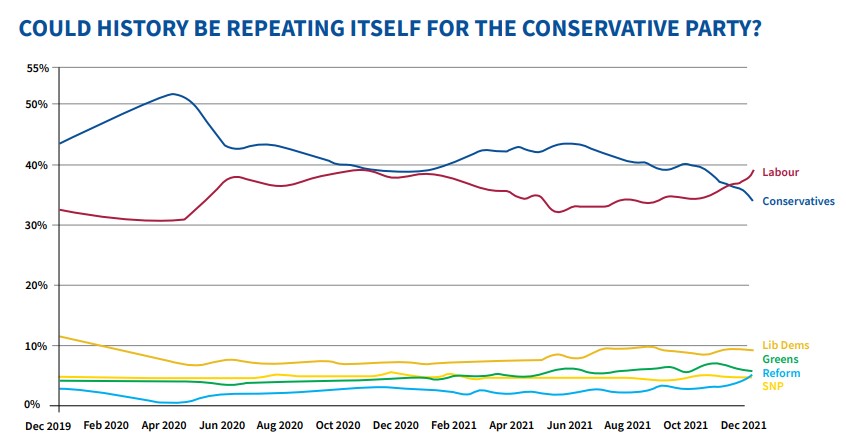

But when looking at the Johnson administration, there’s one comparison that doesn’t immediately jump to mind, but which makes all too much sense once you hear it: His government resembles nothing so much as John Major’s final 1992-1997 term of office.

The Conservatives had been in power for almost 13 years when Major was returned to office in an election that surprised pollsters, with Labour turning in a much worse than expected performance.

But Major quickly turned out to be in office, but not in power. More than a decade in government helps a political party accumulate a lot of backbench resentments and former ministers who aren’t easy to corral.

The Tories of the 1990s were out of big ideas, and so lurched from crisis to crisis – hampered still further by an endless parade of sleaze-related scandals, with everything from affairs to literal brown envelopes full of cash being handed over for parliamentary questions.

Politics has, of course, changed a lot since the 1990s. For one thing, no one needs to bother with brown envelopes any more – politicians have found much slicker ways to enrich themselves in much larger amounts, and have largely come up with rules that somehow allow this.

Payments can come via bank transfer now, in full view – no need for the grubbiness of cash in envelopes. But beyond that technological and regulatory leap forwards, Boris Johnson’s Conservative government of 2021 has almost everything else in common with Major’s sclerotic 1990s administration.

Johnson’s Cabinet is largely made up of the dregs of the talent available to the Conservatives after a decade in government. The longer a party lasts in office, the more people have been excluded – either fired for a scandal, needing to move on after too long in a department, wanting to make their money on the corporate and public speaking circuits, or simply for backing the wrong person as leader.

Eventually, your strongest available picks for Cabinet are people previous leaders would have laughed out of contention for even the most harmless of junior roles. Such is the hand dealt to leaders like Johnson, who is the third PM in a row from the same party.

The same mess happens with the ideas needed to a drive government. Because different MPs came in under different leaders, with very different manifestos, they are often left completely at sea as to what it is they are supposed to believe in today.

Johnson himself clearly suffers from this confusion. By tradition, Johnson was a liberal conservative – somewhat pro-immigration, antinanny state, and pro-civil liberties.

It is not the prime minister’s fault that someone with his instincts was resident in Number 10 for the coronavirus pandemic.

It might be ironic that Johnson was the prime minister to (temporarily) make casual sex illegal, to introduce lockdowns, and to close the country’s pubs, clubs, theatres and cinemas, but it’s hard to actually blame him for that.

Johnson is, at worst, an accidental Oliver Cromwell figure. Where he can be blamed is for his wider incoherency. He is a politician who has always declined to comment as to whether or not he’s tried cocaine, but spent the early portion of December wearing a police beanie hat, warning middle-class drug users he was coming for them.

That’s just one flavour of many – Johnson made a big deal of having decided austerity was, on reflection, a very bad thing and that it would be over in his government. The problem was no one appeared to see whether or not his chancellor agreed with him – leading to Rishi Sunak announcing modest departmental spending increases while looking like he was chewing on a wasp.

Neither Johnson nor Sunak are natural tax hikers, and yet that’s another of their most significant policy decisions: the UK government tax take is set to hit an all-time high under this government. It’s not clear whether any of them have noticed.

The one clear bit of policy the government has makes for a very clear slogan, but very unclear policy. That is, of course, “levelling up”: acknowledging that many smaller towns (and rural areas), especially in the north, have been left behind over the past few decades, and could do with some focused support to help catch up.

So far, the government has skipped boring steps such as reversing drastic cuts to local government that hit exactly those areas hardest, in favour of convoluted new plans to make more largely impotent majors or “governors” – relying on the British public’s deep-seated love for administrative reform.

Otherwise, the flagship achievements of levelling-up so far have been to cut back investment in rail in the north, and to pledge to move various civil service jobs into the north. A photo opportunity to highlight this earlier in the month saw Rishi Sunak posing in a Christmas jumper alongside Treasury employees who had moved to the department’s new “hub” in Darlington. There were 10 people in the shot – the Treasury directly employs more than 1,100 people.

The biggest difference between Johnson and Major’s governments is that Johnson has a landslide majority, whereas for most of his term Major was effectively running a minority government.

But in some ways that favours Major, rather than Johnson. His administration was largely out of ideas, but couldn’t pass any old flight of fancy that crossed their mind.

Because he had a majority of 80 after his landslide 2019 election win, Johnson can rapidly pass all sorts of incoherent legislation that even his own ministers would surely stop if they had time to notice.

The government is set to pass a bill creating a second-tier form of citizenship for those automatically eligible for a foreign citizenship – among other things, casually reducing every Jewish family in the country to that status, a move hardly without historical problems.

Conservative backbenchers are shouting blue murder about civil liberties over mild coronavirus restrictions while nodding through fundamental curbs to protest. The government doesn’t even like the Brexit deal upon which it got elected.

Johnson’s backbenches are fractious and divided, but the majority is large enough that the rubbish becomes law anyway. This is the drunken 2am government – it should have gone home or sobered up hours ago, but is still out and flailing. The night won’t end well and the hangover will be terrible.

The final big difference is between Major and Johnson as individuals.

At the time, Major largely escaped any of the allegations of sleaze hitting almost the entirety of the rest of his Cabinet – despite having an affair with Edwina Currie at the time – and has subsequently managed to secure elder statesman status for himself. The same does not hold true for Johnson.

He has a long history of affairs and shenanigans in his personal life, and has already had one ethics advisor resign in disgust at his handling of scandals. He’s under investigation for his own donations.

Even the most obvious of issues turns into more exhausting nonsense with Johnson – in a way that comes to feel wearily inevitable.

Not having a party when you’ve cancelled Christmas for millions is obvious. The fact Number 10 appeared to have done so felt inevitable, as did the inevitable week-long denials.

Video footage emerging of advisors joking about the party everyone had spent a week denying? Of course. Johnson claiming to be outraged and have heard all of this just for the first time now? Naturally.

A picture emerging of Johnson doing a guest turn at one of the parties he denied happening? What else would we expect?

Johnson wanted us to think his was a new government, with new ideas and new energy.

What he’s shown is, no matter how big his majority, how many PR efforts he tries, his government is just tired.

As are we all.