Here we go again. Fresh suggestions come daily that Boris Johnson’s departure is imminent. The latest theory is that the Conservatives will do so badly in next week’s elections that their MPs will submit enough letters to Sir Graham Brady, the chair of the 1922 Committee, to trigger the process for booting Johnson out of No 10.

Maybe. Johnson’s premiership is like an aircraft wing with metal fatigue. We can be sure that it will collapse one day, but we can’t tell when. It’s even possible his position will have become critical by the time you read these words.

The significant thing is that the prime minister hasn’t gone already. The torrid events of the past few months, ranging from Johnson being Britain’s first PM to be punished for committing a criminal offence, to rising inflation, crippling energy prices and a record drop in living standards, should have settled the matter before now. Why hasn’t it? The hard truth is that different sets of evidence can be cited to demonstrate either that Johnson is doomed – or that he isn’t.

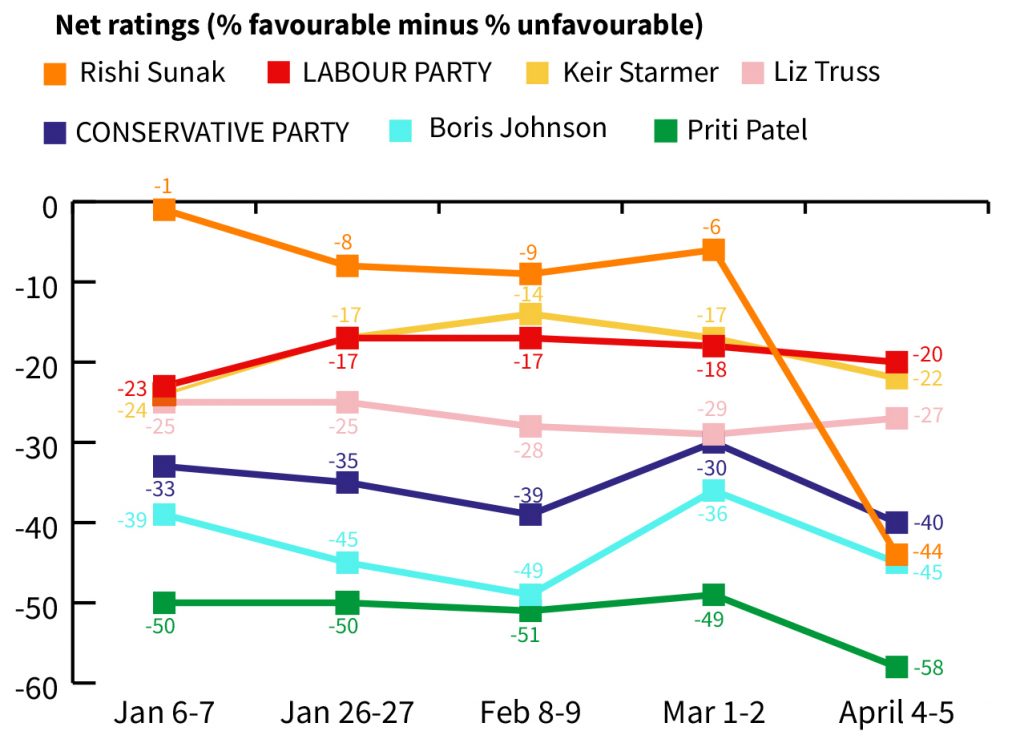

Start with the bad news for the prime minister. His ratings are terrible. The latest YouGov data finds that just 24% say they have a favourable view of him, while 69% say “unfavourable”. That produces a net rating of minus 45, even before his fine for breaking Covid rules. No PM has ever fallen that low and gone on to win the following general election.

As the top chart opposite shows, Johnson had an even worse rating, minus 49, when stories about Partygate were at their most intense in early February. The Ukraine war has helped him – but only slightly. Just as seriously, his rating is even worse than that of his party, which stands at minus 32. Far from lifting Tory support, he is dragging it down.

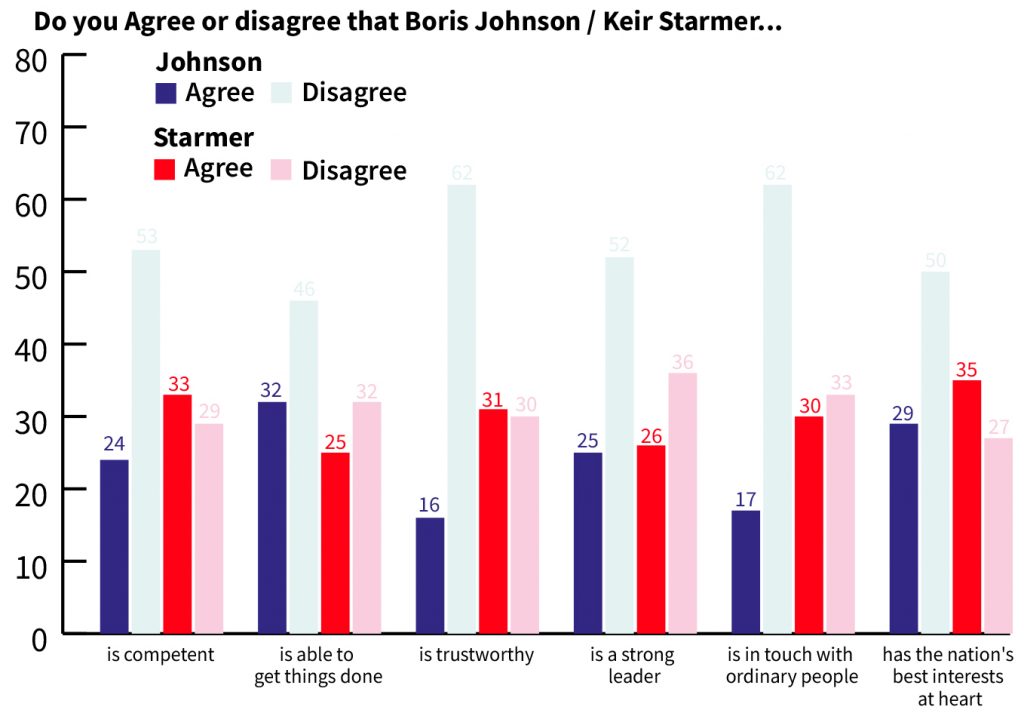

An Opinium survey (opposite, centre) pinpoints Johnson’s greatest weaknesses. By margins of almost four to one, voters say he is untrustworthy and out of touch. His ratings on other character judgments are also bad, if not quite as disastrous. On all six characteristics, Sir Keir Starmer’s net score is far better than Johnson’s.

However, it is not just Johnson’s character that is dragging down Tory support. His signature policy at the last election – “get Brexit done” – is not going well. By a consistent 10-point margin – typically 49%-39% – voters now tell YouGov that the UK was wrong to leave the European Union.

Opinium, asking a slightly different question, produces an even sharper divide. By almost two to one – 58%-31% – voters think Brexit is going badly.

That does not mean voters are clamouring by a large majority to rejoin the EU. Polls paint a mixed picture, but most point to something close to a 50-50 division. Offered four policy options, the most popular is, indeed, rejoining the EU – but the figure is still only 30%. What is striking is that the second most popular option is a form of Brexit that brings the UK closer to the EU – 25%. Together, those two groups add up to 55% – far outnumbering the 33% who want the UK-EU relationship to stay as it is now (18%) or grow further apart (15%).

This indicates that hard-line Tory Brexiteers may be popular with party activists – but not with the wider electorate. To be sure, EU policy is playing little part (other than in Northern Ireland) in the local election campaigns; but Tories may be fooling themselves if they think it will be to their advantage to beat the Brexit drum at the next general election.

Now to the evidence that offers Johnson a glimmer of hope. The first is Rishi Sunak’s near-certain demise as a possible successor. At the start of the year, Sunak was by some margin the most attractive leading Tory to the public. An Opinium poll indicated that the Conservatives would save the seats of around 60 MPs who might lose under Johnson. The demise of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership in 1990 was given a shove by similar polls that demonstrated her electoral liability.

The point is that only Sunak had this effect on voters. And as the top chart shows, Sunak’s appeal had evaporated following his rises in tax and inflation. Subsequent controversies over his Partygate fine and his family’s tax and Green Card arrangements won’t have helped. No longer need Johnson fear a challenge from the man who for some months was his most obvious successor.

Johnson’s other hope lies in the reputation of the Labour party and its leader. As the top chart shows, Labour and Starmer have negative ratings; and on his personal characteristics, (middle chart) the leader’s scores hover in the region of one third positive, one third negative, one third don’t know. If Johnson’s problem is that most voters actively dislike him, Starmer’s is that, more than two years into his party leadership, he remains an enigma to huge numbers of voters.

Looking ahead, the lesson from past parliaments is that oppositions tend to see their mid-term polling numbers shrink as the following general election approaches. For many voters, the mid-term appetite for change, when the prospect is a year or two away, gives way to the sentiment of better-the-devil-you-know.

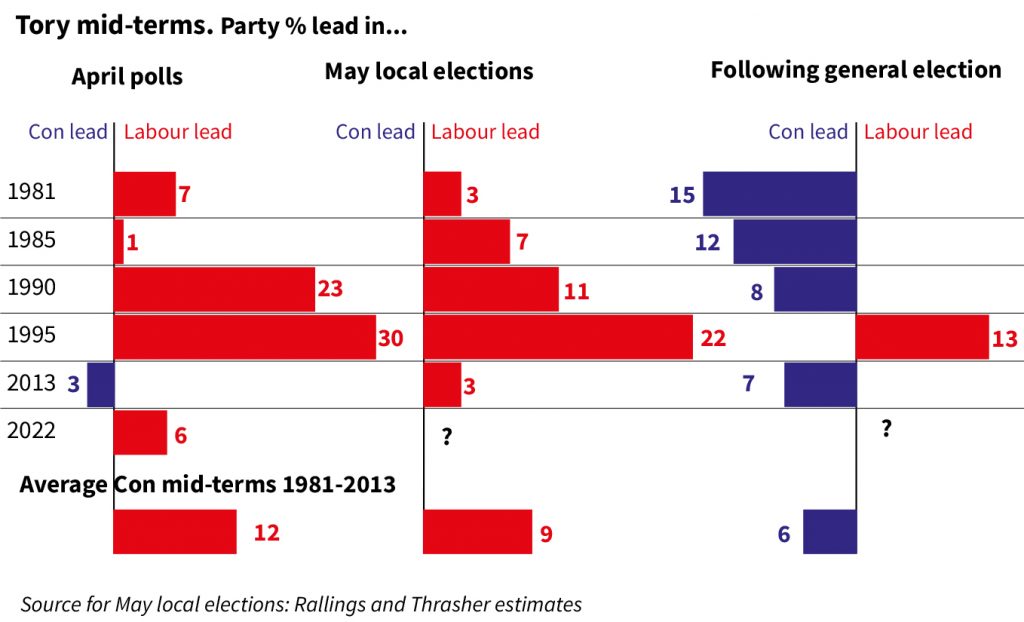

This brings us to the relevance of the May 5 local elections to Johnson’s and Starmer’s prospects. The final table shows what happened at the equivalent stage of Tory governments in the past 40 years. Compare first the polling leads in the run-up to those local elections with the projected national outcome of those elections. The figures vary, in 1990 and 1995 considerably, but the broad-brush stories are similar. When Labour is miles ahead in the polls, it does well in the local elections; when the national race is tight, the local elections show the two main parties reasonably close.

The real story is what happened in the two years after the mid-term contests. The Tories went on to win four of the five following general elections, despite being behind in every one of the local elections held two years before. Even in the one election when Labour ousted the Tories – the Blair landslide in 1997 – there was still a substantial Conservative recovery from their plight in mid-term.

So: how should we judge the outcome of next month’s local elections? Pay little attention to the figures for gains and losses of council seats. Almost half the English seats being contested are in London, where Labour did exceptionally well in 2018. It has limited scope for further gains.

Many of the contests outside London are also in strong Labour areas with few opportunities for further gains.

So Tories who publicly fear a bloodbath are playing the expectations game. They know they are unlikely to lose vast numbers of councillors. They are simply positioning themselves to claim success, once all the votes are counted.

The figures that should command our attention are the projected Britain-wide share of the vote. The first estimate will be provided by the BBC, sometime on Friday May 6. This will be followed by figures from Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher of Nuffield College, Oxford, on Sunday May 8. These will be based on a wider range of results, but never vary much from the BBC figures.

The Tories are unlikely to end ahead in the national vote share. They have not done this in any of the five equivalent sets of mid-term elections in the past 40 years. Keeping Labour’s lead below 3% should cheer the Conservatives and worry Labour. A Labour lead close to 6% would be par for the course, given recent polls. It would take a Labour lead substantially above 6% for Labour to have reason to cheer. Even then, history invites the Tories not to be too downcast – and warns Starmer not to think too hard just yet about changing the wallpaper in the flat above 10 Downing Street.

There is, though, one big unknown. What if the future diverges markedly from the past? What if there is no big recovery in Conservative fortunes as the next general election approaches? We are living through strange times. Even when the war in Ukraine is over, the combined impact of Covid, inflation, Partygate, and higher taxes – and a prime minister with terrible ratings – might last until the next election, thwart a Tory revival and make past polling patterns irrelevant to the future.

At the start of the 2017 general election campaign, when the Tories enjoyed a double-digit lead, the smart money said that election campaigns make only modest differences to party support. The smart money got that election wrong. Maybe history will be defied again.

After the May 5 elections, attention will turn to Wakefield, whose MP, Imran Ahmad Khan, has been convicted of assaulting a 15-year-old boy. He won this Red Wall seat from Labour at the last election. It’s the 36th most marginal Conservative-Labour contest: precisely the kind of seat that will decide whether the Tories can remain in office.

If there is a by-election and the Conservatives hold on, then this will be a highly significant victory. If he is still prime minister, Johnson will feel he is invincible, at least for the moment. A narrow Labour victory would be a setback, but not necessarily fatal.

A big Labour victory would be more troubling. The Tory MPs who will decide his future may shrug this off as a routine mid-term setback. But, again, the Tories would be relying on history repeating itself, with a big swing back to the government as the next general election approaches. It might turn out like that: but I wouldn’t bet the house on it.