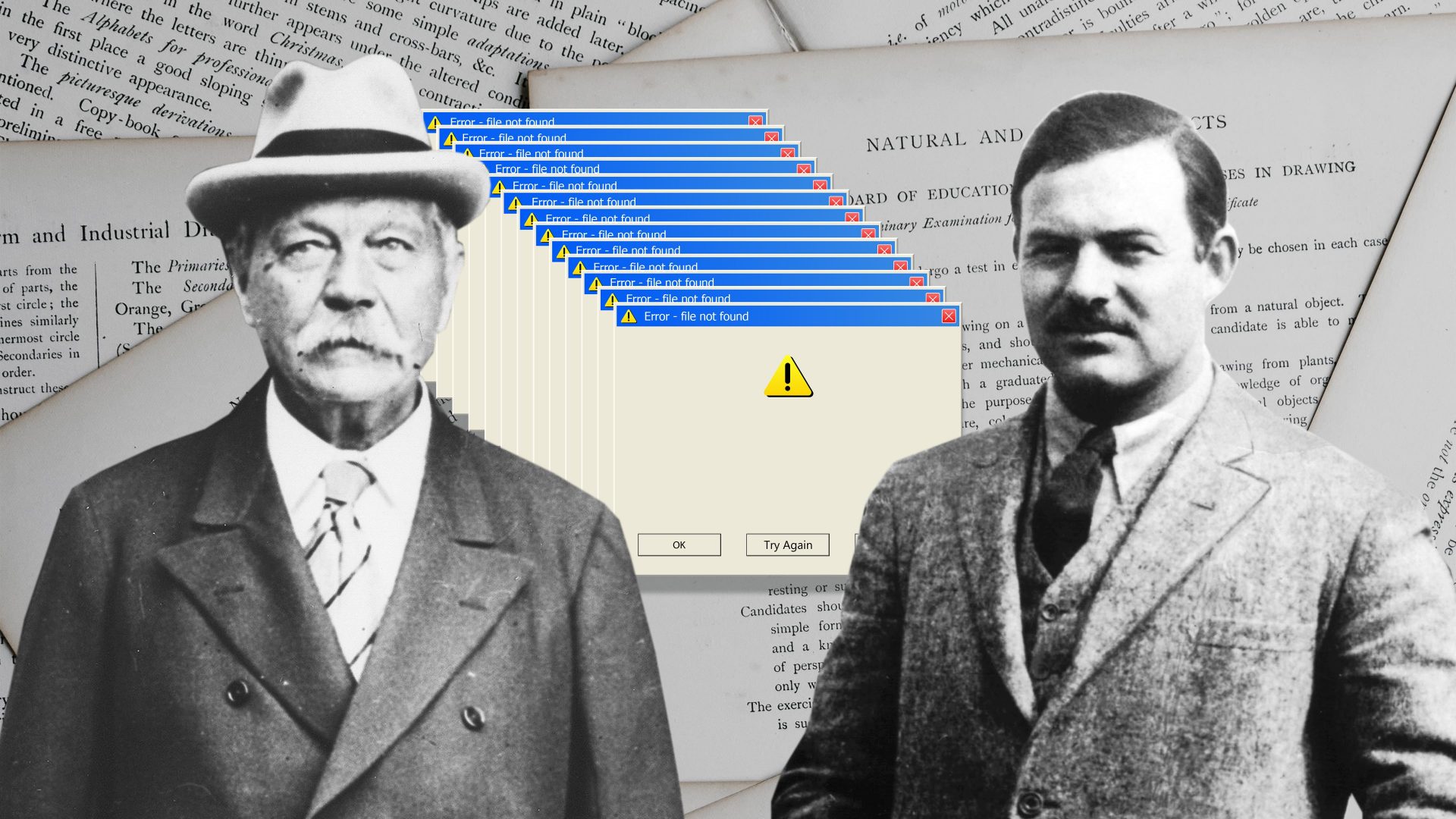

This December, it will be 100 years since a 31-year-old American named Hadley Richardson boarded a train at the Gare du Lyon in Paris, found an empty compartment, stowed her luggage and sat down. Among the bags in the rack above her head was an overnight case containing everything written so far by her husband, aspiring fiction writer Ernest Hemingway, in 1922 a 23-year-old journalist whom she was about to join on assignment in Switzerland.

Hemingway had met the veteran American reporter Lincoln Steffens, who was keen to see more of his writing, and Hadley had scoured their Latin Quarter flat for everything she could find in order that her husband could pick out his best work for Steffens to read.

There were still a few minutes before departure and, spotting a kiosk farther up the platform, Hadley got off the train to buy a bottle of water. Returning to the compartment she glanced up and noticed immediately something was wrong. A bag was missing.

Not just any bag either – the overnight case. The overnight case containing practically everything her husband had ever written, including the carbon copies he’d made to be on the safe side.

Frantically she searched the compartment, then dashed on to the platform and summoned a guard for a more thorough search. Nothing. There was no sign of the case then, and there has been no sign of it in the ensuing century.

“She had cried and cried and could not tell me”, wrote Hemingway later in A Moveable Feast. “I told her that no matter what the dreadful thing was that had happened nothing could be that bad, and whatever it was, it was all right and not to worry. We would work it out. Then, finally, she told me. I was sure she could not have brought the carbons, too, and I hired someone to cover for me on my newspaper job. I was making good money then at journalism, and took the train for Paris. It was true all right, and I remember what I did in the night after I let myself into the flat and found it was true.”

We can only speculate what Hemingway “did the night after I let myself into the flat and found that it was true”, but whether he trashed the place or just sobbed quietly for a bit, it’s a story that will send chills into the pit of every author’s stomach and possibly those of a few authorial spouses, too.

Granted, looking back at some of the books I’ve written, the loss of their manuscripts might have done the world of literature a great service, but

the thought of all that work, all those hours spent writing, editing, shaping, honing and polishing, then the whole caboodle disappearing for ever, well,

it’s enough to have any author waking up shouting and sweaty in the middle of the night.

I shudder a little when I think back to my first book and not just because it was largely cobblers. It was the late 1990s, just before everyone had this new-fangled thing called email, and on finishing the book I carefully printed out the whole manuscript, put it into a jiffy bag, walked round to the post office and sent it to the publishers. I couldn’t afford recorded delivery so it just went second class, its fate entirely in the hands of the Royal Mail once it had been tossed into a sack behind the counter.

Now, before you start, I wasn’t entirely reckless and had sensibly saved the manuscript on to a floppy disk. Which was also in the jiffy bag.

It arrived safe and sound at the publisher a few days later, but what if it hadn’t? Could I have faced starting the whole thing again from scratch? No, I could not. I couldn’t afford to send the advance back either, meagre as it was. To this day it gives me the heebies, and indeed jeebies, thinking about what might have happened had that package gone astray.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wasn’t so lucky. In 1883 he was in his early 20s, living and working as a doctor in Southsea, and had entrusted his first novel The Narrative of John Smith to the postal system. Weeks went by with no reaction from his publisher, until he tentatively wrote again asking what they had thought of his manuscript. A few days later the reply came. What manuscript?

The Narrative of John Smith never arrived and was never seen again. Conan Doyle later decided this was no bad thing, writing that, “my shock at its disappearance would be as nothing to my horror if it were suddenly to appear again – in print”.

Lost manuscripts can attain a mythical status. We know that Shakespeare wrote plays called Love’s Labour’s Won and The History of Cardenio but no copy of either has survived. Famously, Lord Byron’s scandalous memoirs were burned after his death by his publisher, John Murray, in an attempt to protect his reputation. William Blake’s papers, including entire unpublished

manuscripts, were entrusted to a friend who subsequently became involved with an evangelical church and burned them as heretical. Similarly, Nikolai Gogol had written two further volumes of Dead Souls, which he destroyed at the insistence of a clergyman.

However horrifying these losses sound to the literary scholar, they were at least deliberate. It’s the accidental disappearance of an author’s work that really breaks the heart and, for writers at least, chills the blood.

Staying with immolation, spare a thought for the Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, who in 1942 had sent the manuscript of a detailed work of

literary criticism on 18th-century German literature to his Moscow publisher. A heavy smoker at a time when wartime shortages made cigarette papers scarce, knowing that the book was safely in the hands of his publisher he began tearing strips from the pages of his duplicate copy to roll

cigarettes. By the time he learned that his publisher’s office and everything

in it had been destroyed by a bomb, Bakhtin had smoked his own book.

Fire also accounted for the first volume of Thomas Carlyle’s The French Revolution: A History. He had sent it to John Stuart Mill for comment, but when Mill appeared at Carlyle’s door one night in 1835 he was in a state of

some agitation. He had left the manuscript in his kitchen, he said, only for his housekeeper to use it as kindling for the fire. The whole thing had gone up the chimney. Mill was so distraught that Carlyle ended up consoling him rather than vice versa, then set to work writing the second and third volumes before going back and rewriting the first in time for the whole thing to be published just two years later.

If it’s not flames, it’s transport. A few days before Christmas 1919, TE Lawrence passed a few minutes between connections in the buffet at Reading station. It was only when he had boarded the train and was

steaming west through Berkshire that his stomach turned over with the

realisation that he’d left the entire – and only – manuscript of Seven Pillars

of Wisdom, running to approximately 250,000 words, under a table in the

buffet.

Tumbling off the train at Oxford he phoned Reading station, but there was

no sign of the book and nothing had been handed in. Notices were placed in newspapers appealing for its return, but nobody came forward. Lawrence’s

seven pillars had, it seemed, effectively been toppled by a quick cup of tea and a pork pie. Undaunted, he set about rewriting the book from memory and somehow within three months had produced an entirely new version.

That was much quicker work than Jilly Cooper, who in 1970 also sent out an appeal via the newspapers. “If any traveller found a blue envelope file stuffed with pink paper typewritten in red on the seat of a number 8 bus on Guy Fawkes’ Day the journalist Jilly Cooper hopes against hope that he hasn’t used it to get a brighter blaze from his bonfire,” said the Evening Standard. The file, containing the manuscript of her novel Riders, didn’t show up and it took until 1984 for Cooper to complete a rewrite. What should have been her first novel turned out to be her 12th, but still became one of the biggest-selling books of the 1980s.

Today technology makes duplicating and backing up a manuscript the matter of a single click. It’s almost impossible to leave your work irreplaceably on a train and it’s rare for email attachments to go astray. Even if they do, it’s the work of seconds to send them again.

None of which, of course, would have been much consolation to Hadley Richardson as her train clanked through the Parisian suburbs and into the countryside a century ago while in a garret somewhere behind her, a thief opened a bag containing nothing more valuable than the entire early works of Ernest Hemingway, swore under his breath and began feeding the papers into his stove.