One of the more chastening experiences of this time of year is looking back at the year’s notable fiction and realising how much of it you have not had the chance to read. A glance at my bedside table reveals a pile of novels I am definitely getting to at some point, and will reach them once I can climb over the stacks of similar volumes piled next to the bed. As for my office, well, there’s probably an office in there somewhere, under all those unread novels.

Anyway, let’s dive in to the fiction year in review, starting in the traditional manner with the prize winners.

The Booker was won by Samantha Harvey and her novella Orbital (Vintage, £9.99), a quiet, contemplative work that spends 24 hours with a group of astronauts circling the Earth in a space station looking down on our planet and witnessing from orbit sunrises and sunsets almost hourly. There is something profound about Orbital and I enjoyed it very much but I didn’t think it was the strongest contender on this year’s Booker shortlist.

Anne Michaels’ Held, (Bloomsbury, £9.99), reviewed glowingly in these pages, and Percival Everett’s James (Mantle, £20), which re-tells The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Jim, both had very strong claims, I felt, but this probably just explains why I will never be a Booker judge.

The International Booker went to the splendid Jenny Erpenbeck, long admired in these pages, for Kairos (trans. Michael Hofmann, Granta, £9.99), her terrific account of an intense affair between a married writer and a student in 1980s East Berlin.

The Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse prize for comic fiction and the Waterstones Debut Fiction award went to Ferdia Lennon’s original and imaginative Glorious Exploits (Fig Tree, £16.99), set in Sicily in 412BCE and based on real events, while the overall Waterstones Book of the Year went to Butter by Asako Yuzuki (Fourth Estate, £14.99), the story of a gourmet cook who also happens to be a serial killer.

The Women’s Prize, which for me boasts consistently the highest quality shortlists and winners of all the literary bunfights, went this year to Brotherless Night by VV Ganesha-nanthan (Penguin, £9.99), a glorious immersion in the world of Tamil women during the turbulent 1980s.

A first for me this year was reading and enjoying two very different novels with almost exactly the same title. Elizabeth O’Connor’s debut Whale Fall (Picador, £14.99) explores life on a small island off the coast of Wales in the late 1930s from the perspective of Manod, a young woman wondering what the future might hold and whether that future might lie across the water on the mainland. O’Connor’s sparse prose works beautifully here, allowing the reader to really climb inside Manod’s character, and I can’t wait to see what this gifted writer does next.

Whalefall by Daniel Kraus (Zaffre, £9.99) is a wholly different novel, however, in which the son of a renowned diver lost off the coast of California goes in search of his remains, only to be improbably swallowed by a sperm whale leaving him with only an hour of oxygen to escape the mammal’s four stomachs. Visceral, claustrophobic and deeply human in its portrayal of the strange ways in which grief can manifest, Whalefall is incredibly tense and utterly unputdownable.

In Lerwick a couple of weeks ago I picked up the new novel by Shetland author Malachy Tallack. I’ve long been an admirer of his work so to immerse myself in That Beautiful Atlantic Waltz (Canongate, £18.99) on its home territory gave an extra dimension to an already superb novel. Having written an exploration of time, loss, loneliness, hope and the incredible power of music, in parallel narratives 50 years apart set in the high and low latitudes, the author has also written songs to accompany the book. These, along with his mellifluous voice, make the audiobook version particularly appealing.

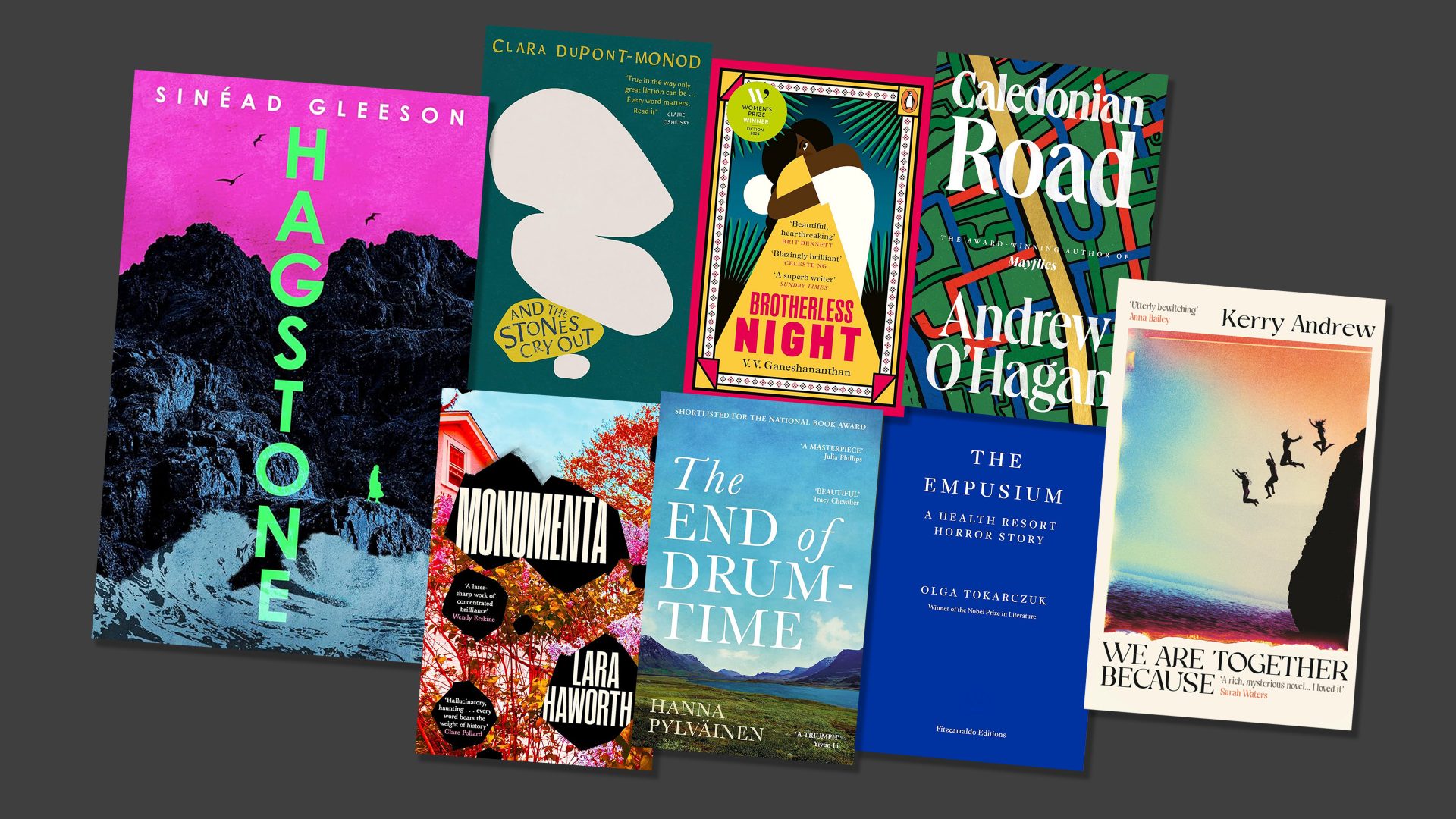

Staying with islands, a book I really enjoyed this year was Sinéad Gleeson’s debut novel Hagstone (Fourth Estate, £16.99), set on an island off the west coast of Ireland that’s home to a disparate scatter of established islanders and blow-ins including Nell, a contemporary artist who is, like many who relocate to remote places, seeking escape. Also on the island, secreted away in an old convent, is a community of women, not a religious order or a cult, it seems, but a refuge and a haven where women, many of them vulnerable or recovering from trauma, can feel safe.

When Nell is invited to create a work of art for them it brings together the island’s two communities for the first time, with inevitable consequences. A dazzling feminist exploration of island life and dynamics, the physical toll life takes on women’s bodies and the pain that goes with it, and the thrumming eeriness that accompanies our lives at a frequency very few can hear, Hagstone is a fabulous debut.

Another superb novel with an underpinning of the eerie is The Empusium by the Polish Nobel prize-winning author Olga Tokarczuk (Fitzcarraldo Editions, £14.99). Subtitled “A Health Resort Horror Story”, The Empusium is set in a remote Silesian mountain village to which sufferers from respiratory diseases decamp to benefit from the purity of the air. This is a proper old-fashioned horror tale in which the landscape itself becomes sinister, while the misogyny and aggressive masculinity of the male residents is almost as horrifying as the story itself.

“His father believed that blame for both national disasters and educational failures lay with soft upbringings that encouraged girlishness, mawkishness and passivity,” Tokarczuk writes of her protagonist.

From northernmost Europe, I enjoyed The End of Drum Time by Hanna Pylväinen (Swift Press, £14.99), set among the Arctic Sami territories where modern Russia, Finland, Sweden and Norway meet. Based on a real 19th-century preacher, The End of Drum Time charts the encroachment of southern Europeans into the far north of the continent, their attempts to convert the indigenous population to Christianity and the oppression that customarily went with it.

Beautifully evocative of the landscape, this vivid exploration of borders, imperialism, religion and bigotry is also, at heart, a love story. A bleak, barren setting adds an agreeable claustrophobia to the narrative that leaves the reader almost smelling lamp oil on their clothes and brushing snow from their shoes.

In warmer climes, Clara Dupont-Monod’s And the Stones Cry Out (trans. Ben Faccini, MacLehose Press, £16.99) won the Prix Femina and sold more than 400,000 copies when first published in France in 2021. Its portrait of a family living in a remote part of the Cévennes and the dynamics caused by the presence in the family of a child with serious physical issues is taut, vivid and deeply thought-provoking.

Closer to home, Andrew O’Hagan’s Caledonian Road (Faber & Faber, £20) was one of the most keenly anticipated novels of 2024. A sprawling skewering of modern Britain with a vast cast of characters, few writers could pull off this comprehensive portrait of the nation today while retaining their grip on a compelling narrative.

Fortunately, O’Hagan is one of Britain’s most gifted writers and this complex novel of race, class, corruption and liberal guilt never stops rattling along at a terrific clip. From people seeking asylum to the highest echelons of the aristocracy, Caledonian Road is a remarkable polyphonic snapshot of the nation in which we live, its characters given impressive depth and nuance despite the lengthy cast list.

Is this O’Hagan’s masterpiece? Well, it isn’t Mayflies, his beautiful and heartbreaking evocation of male friendship and the passing of time that was adapted faithfully for television – andfor which he paused work on Caledonian Road to write – but this is a different beast altogether, a novel that captures its times and the imagination in the same way Zadie Smith’s White Teeth did at the turn of the millennium.

It’s too early, perhaps, to dub it his masterpiece, not least because one hopes there is still considerably more to come that might qualify for that title, but Caledonian Road is certainly right up there as one of the best novels of the year.

Lara Haworth’s slimline Monumenta (Canongate, £12.99) could fit inside Caledonian Road several times over, but its darkly comic tale of a Belgrade home designated as a memorial site where nobody is quite sure what to memorialise and how, not to mention the fact a woman still lives there, is a wise and eloquent exploration of the nature of memory and commemoration in the Balkans and beyond. Intelligent, witty and pitch perfect in tone, Monumenta’s concision is part of its strength. A gem.

Of all the novels I read that were published this year, however, there was one that really stood out, a novel that I couldn’t get out of my head for days after finishing it and still think about even now, months later.

Many of us have probably had enough of actually living through dystopia to require it from our fiction choices, but in We Are Together Because (Atlantic, £16.99) Kerry Andrew has written a novel that is not only dystopian but also features the end of the world viewed through a nuanced portrayal of contemporary family dynamics.

We experience the apocalypse through two sets of half-siblings gathered at their father’s holiday home in a remote corner of south-eastern France for a holiday designed to bring the two sides of the family closer together. The father is on a business trip in China and is planning to join them until, well, until humanity starts being wiped out in mysterious circumstances.

Hence the first part of the novel is a frequently moving eavesdrop on the siblings’ group dynamic, a mixture of affection, joy, confusion, defensiveness and awkwardness. This could possibly have made an effective novel in itself, but Andrew then throws in the end of the world to make things even more messy for them.

“They were a family,” Andrew writes, “and at the same time, they weren’t – two sides stuck together with Sellotape.”

The end times arrive slowly, almost gently, the remoteness of the setting meaning we share the siblings’ confusion and growing alarm in a perfectly paced and beautifully written literary thriller.

The heaviness of the summer heat adds to the oppressiveness of the coming disaster, which makes the landscape and the changes the protagonists notice in it part of the story. For all the dystopia, however, there is hope, beauty and, on occasion, even joy. We Are Together Because is a magnificent novel by a terrific writer, and is my New European fiction book of the year.