Spring is coming. On good days you can feel it in the air, see it on the ground in green shoots, hear it as it comes pouring down from treetop and chimney pot in the form of song: the glorious British or English spring – such a comfort after a winter in which Britain has been under constant invasion.

That, of course, was the word chosen by the home secretary Suella Braverman back in November. She used it for the people seeking asylum in the UK: the people who, apparently, threaten the Englishness of England, the Britishness of Britain and the very existence of the UK… for that is what invasion means. Now she and Rishi Sunak are cracking down on these “invaders” with their legally questionable policy on small boats.

But let’s take our minds off the threat of asylum seekers and concentrate on what it is they supposedly threaten: the very heart of our nation: the British or English countryside. Let’s start with a chestnut tree, already in bud, buds that will soon reveal their deeply fingered leaves. The tree will then produce great candelabras of flowers, and after that thousands of the prickly fruit that small boys used to open and plunder, so they could put the shining nuts to the test.

At the foot of this tree there are half a dozen hares at urgent play – mad March hares, the lust of spring already strong in them as they chase and box, working out who will mate with whom. Beyond them the land falls away to a classic English river, lined by weeping willows, already a sharp yellow-green with their buds almost bursting. Soon they will be decked with long fronds of gentle leaves reaching down to the water. Spotted, broad-antlered fallow deer graze the sward on the far side of the river to complete this vision of the English pastoral.

But wait – there’s more – between horse chestnut we can now see a cock pheasant strutting in all his splendour, having survived and no doubt heartily enjoyed the thrilling sport of the winter. He’s ready to father more broods of pheasants to add their beauty to the countryside of Britain.

Every one of those species is an invader. At least they are in Suella terms: technically speaking an invasion involves weapons of war and an ambition to take over the government – you know, like Russia and Ukraine. Not that Britain is short of stories of genuine invasions as well as many more of the Suella kind, and we’ll get to them in a moment.

The horse chestnut tree was brought to Britain in the 17th century and the weeping willow came in the 18th; there’s a story that Alexander Pope grew the first one in his garden at Twickenham. Hares were probably brought over by the Romans, fallow deer by the Normans, so they could have the fun of hunting and killing them. And, without human involvement, pheasants would be no closer than the Black Sea, but we introduce them into our countryside – bird flu or no bird flu – at a rate of 50 million a year, so they can be shot. No, that’s not a typo: I mean 50,000,000. Here, then, is a suite of invaders, all them widely loved.

But we’re picky about invaders. We don’t love them all. I remember giving a talk about one of my wildlife books in Barnes, west London. First question: “What are we going to do about the ring-necked parakeets?”

This is a non-native species; they were kept as pets and released when the novelty wore off. West London is a hot spot. They’re loud and flashy and attract both admiration and resentment. I suggested that we learn to love them, because they’re here to stay and the only other option is to

use them as fuel for your atavistic hatred of invaders. My questioner sniffed. She seemed committed to the second option.

Gary, a Cornishman of my acquaintance, was asked why he voted for Brexit. “Because I don’t want Isis marching down Poldhu Lane,” he explained. You can’t argue with facts like that.

The fear of invasion is common to all humans. It was exploited by Donald Trump with fair efficiency: he was carried to power on the promise that he would build a wall between the United States and Mexico and the Mexicans would pay.

But perhaps fear of invasion is linked to your degree of isolation: and perhaps it increases when you live on an island. An islander is by definition special – different to the vast majority who live on those vulgar continent things. I used to live on Lamma Island, south of Hong Kong: I commuted by ferry and when a typhoon struck I was isolated, precisely as you would hope. It was my island and I loved that.

Winston Churchill wrote a book entitled The Island Race. He had a deeply romantic view of the people who inhabit the island of Britain and believed their moral superiority made them the natural and inevitable makers and rulers of an empire. We were – and are – islanders. Time and again the Brexit tub-thumpers hammered the same phrase: “We’re a proud island race”.

Churchill gave us the second-most stirring bit of rhetoric about the island of Britain with his promise that “we will fight them on the beaches”: an image of defiance that endures today, even though the people who tread those beaches are not the armed soldiers of a hostile nation.

Churchill is only topped by John of Gaunt in Richard II, Shakespeare’s famous “sceptered isle” speech: “This fortress built by nature for her self… against infection and the hand of war…”

But the truth of history is that we’re not a race, in the sense of a homogenous people all of one blood, and our isolation – our total surrounding by water – is of dismayingly recent date. We are not who we think we are.

Those with long memories will recall the anxiety that surrounded the building of the Channel Tunnel and the genuine fear that French dogs would travel its length and start biting British humans and infecting them with rabies. Baroness Trumpington, a government minister, had to address the House of Lords on the subject, assuring the peers of the elaborate precautions that were in place.

There hasn’t been a single case of rabies by sub-channel canine transmission… so either the precautions were brilliant or it was all a mad irrational fear. The New York Times reported that the British were “uniquely, stubbornly obsessed by the disease”, but they were wrong. The British obsession is invasion: on this occasion a vision of French dogs marching the 50km length of the tunnel with madness in their eyes and hydrophobia dripping from their jaws.

The south of England was directly connected to the north of France by the Weald-Artois Anticline, a chalk ridge. This survived until 160,000 years ago. Britain was also connected with the continent via Doggerland: now submerged and known as the Dogger Bank. This stretch of water (or land) lacks the emotional impact of the channel, but it satisfactorily connected East Anglia with Holland until the end of the last Ice Age and the subsequent rise in sea levels from the meltwater: that is to say, about 6,000 years ago. Today the sea above Dogger Bank is mostly less than 20 metres deep.

Britain is a country of the north, so the succession of Ice Ages affected it more than places farther south. Britain was only intermittently habitable until recently. Ancient human remains and artefacts have been found dating back 100,000 years, but there has only been a continuous human presence for a few thousand. The place was periodically empty and uninhabitable, and then conditions changed and Britain was once again an invasion-opp.

Our prehistory is a succession of invasions. Without these invasions – in the Suella definition of people looking for somewhere to make a living – there wouldn’t be any British people at all. Neolithic culture in Britain has been dated back 6,000 years and it was a result of invasion from people who had their origins in Anatolia in west Asia: dark-skinned, dark hair, blue eyes. The Beaker people from central Europe followed. The origin of the Celts is full of controversy: perhaps they came from the Iberian Peninsula, or from what is now France, or maybe central Europe.

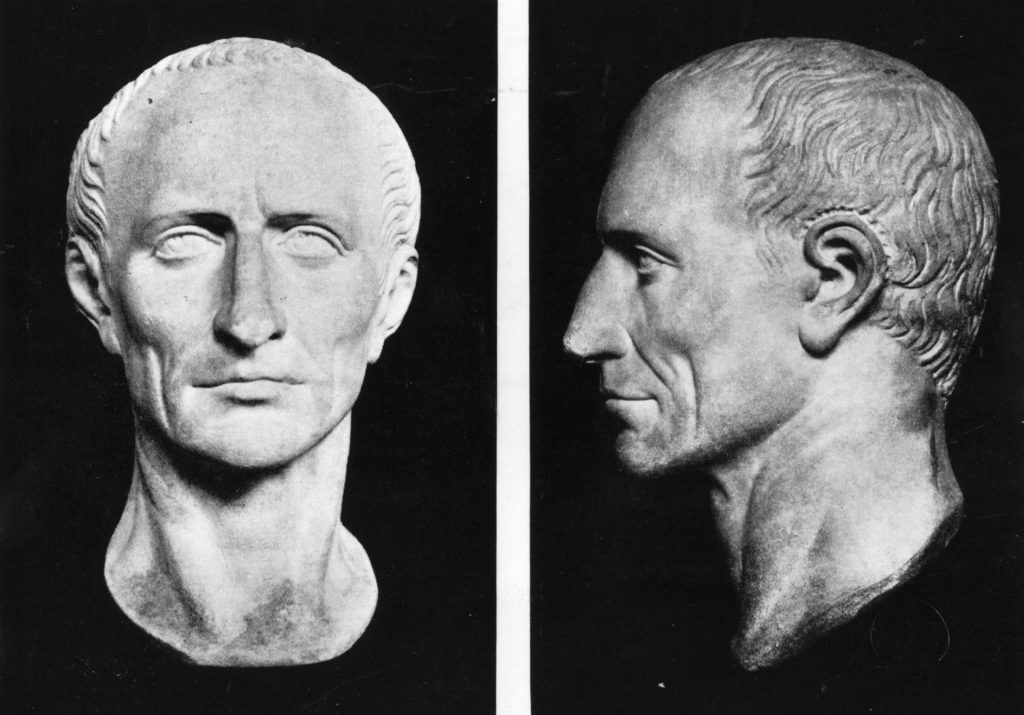

Julius Caesar’s invasion of 55BC was more about trade than conquest, but later on Claudius launched a full-scale invasion (in the Putin rather than the Suella sense) and brought 38 war elephants to do the job properly. He was resisted by the Celtic Queen Boudicca in East Anglia, and you can see her statue on Westminster Bridge. If you walk round the plinth you can read an accompanying quotation from William Cowper, which contains one of the greatest Proud Island Race boasts you will ever find:

Regions Caesar never knew

Thy posterity shall sway.

As the Roman Empire declined (but long before the British one did) other races moved into Britain: Angles, Saxons and Jutes from Germany from about 400AD, and Viking raiders from Scandinavia from about the eighth century. The French added to this mishmash of bloods when William I arrived in 1066, burning his boats as he did so in order to launch a proper invasion, even if he lacked the elephants. Raids from Scotland continued across the centuries. The Spanish Armada of 1588 was an attempted invasion; the Battle of Cornwall of 1595 was a follow-up.

The last successful invasion of Britain was the Glorious Revolution of 1768-9, and it was at the same time a Dutch conquest and an internal coup. Its result was to put Mary II and then William III (William of Orange) on the throne of England.

It’s only since then that attempts at armed invasions have been unsuccessful. But both before and since people have been coming to Britain without weapons and from many different places. Jews were allowed in under the Normans (post 1066) and were duly persecuted. Weavers arrived in Norfolk seeking work. Protestants came over to escape persecution from Catholic rulers; in the 17th century French Huguenots continued this pattern.

In the 18th century there was immigration from Germany, including Handel the composer and William and Caroline Herschel, the astronomers. It became fashionable to import black servants. The potato famine in the 1840s brought many people across the Irish Sea. Indian and Chinese people and Russian Jews came in the 19th century.

Czech and Polish people arrived during World War Two. After that there was immigration from the Caribbean in the 1950s and in the 1960s from South Asia. In the 1970s Ugandan Asians fled persecution and came to Britain. Irish and Polish immigrants arrived early in the current century. In short, what Suella calls invasion has been and is a continuous process throughout history and prehistory.

There are only 35 species of native trees in Britain: all the rest came via human hands, including such quintessentially English species as apple, copper beech, holm oak, walnut and Leyland cypress or leylandii.

Introduced animal species include red-necked wallaby, yellow-tailed scorpion, little owl and red-legged partridge; lost British species that have been reintroduced include white-tailed eagle, beaver, large blue butterfly and, most recently, European bison.

In other words, no matter what life form you choose, there is no very precise distinction between British and non-British: between what is truly of the island and what is not. It’s a muddle: and we can all of us, including the royal family, trace our mongrel mudblood ancestry back to invaders.

But never mind the facts. The fantasy of the Proud Island Race runs hand in hand with the atavistic fear of invasion, and politicians have never shied away from exploiting either or both. It’s hard to say which is the more dismaying factor in British life: that vote-hungry politicians compete as to who can be nastiest to some of the most desperate people on earth – or that they are admired for doing so. Still, Poldhu has survived another 24 hours without invasion. Pray God it will survive the next.