With Munich still hungover from its New Year celebrations, we can assume the Hotel Vier’s music room was not at full capacity. But when the avant-garde composer and performer Arnold Schoenberg took to its stage on January 2, 1911, a new friendship was sealed and the world of art shifted on its axis.

Painters Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc had met at a party only the day before. Now, as they watched and listened, in the company of fellow artists Gabriele Münter, Marianne Werefkin and Alexej von Jawlensky, Kandinsky became enraptured by Schoenberg’s vision and daring. In place of the eight-note octave that was the bedrock of western music, he proposed that all 12 notes in the chromatic scale had an equal place, to be arranged at will, without obeying the conventions of melody and cadence.

For the painter, this was the untethering from convention that he was attempting in colour and composition. He wrote with enthusiasm to the composer: “The particular destinies and autonomous paths, the very lives and individual voices in your compositions are precisely what I have been looking for in pictorial form.”

The admiration was mutual, and a correspondence ensued. For his part, a year later Schoenberg observed: “Kandinsky paints pictures in which the external object is hardly more to him than a stimulus to improvise in colour and form and to express himself as only the composer expressed himself previously.”

This was atonal music to the painter’s ears. Schoenberg understood entirely Kandinsky’s desire to break free of figurative painting, and with it, the object.

While his works from the early 1900s, as for artists for centuries before, were inspired by and depicted a version of the world around him, by the time of the Munich concert he could borrow from musicians the term to extemporise, in a series of six Improvisations. Impression III (Concert) recalls that night in Munich, with figures simplified to blobs, a giant, floating piano and, to the left of the canvas the four players of a string quartet. The whole flies in an explosion of colour, as the music takes to the air.

Impression III is given a room and a soundtrack of its own in an exhibition at Tate Modern in London, dedicated to Kandinsky, Marc and the other artists at the heart and on the fringe of Der Blaue Reiter – The Blue Rider. The name was chosen almost at random, in the garden of Marc and his artist wife, Maria Franck-Marc, at Sindelsdorf, near Lake Starnberg, south of Munich.

Kandinsky later recalled: “We invented the name Blaue Reiter while sitting around a coffee table… we both loved blue, Marc liked horses, and I liked riders, so the name came of its own accord.”

The new year concertgoers listened to the free-range experimentation of Schoenberg’s Piano Pieces Op 11, his first and second string quartets, and five songs. Franck-Marc remarked on their unresolvable sound mixtures, lack of tonal colour and emphasis on expression. “Kandinsky was very inspired by that,” noted her husband. “That is his aim.”

Once the movement had its name, it needed a manifesto. There followed, in May 1912, the Blaue Reiter Almanac, which included Kandinsky’s stage work Der Gelbe Klang – The Yellow Sound. He considered yellow a particularly resonant colour that advanced towards the viewer: it is a prominent colour enveloping the audience in Impression III.

Devoid of plot, rooted in movement, colour and sound, the piece went beyond what even the progressive director Konstantin Stanislavsky was prepared to stage at the go-ahead Moscow Art Theatre.

Now, discovering Schoenberg, Kandinsky had his musical content for the almanac, which was rare in giving equal prominence to music and art. Essays on music and a facsimile of Schoenberg’s demanding songs for soprano, Herzegewächse, were published alongside work by Cézanne, by Münter and the Russian-born Natalia Goncharova, representing female artists, and an analysis of the colour theory of Blue Rider associate Robert Delaunay.

The Blue Rider was not alone in breaking boundaries at the start of the 20th century. In France, Cubism was already taking apart and reassembling familiar images. Vorticism was excited by the suggestion of movement within the single image.

In 1905, Matisse had painted Madame Matisse with a green nose. Gauguin had found, on observing them dispassionately, that tree trunks were purple. In Britain, the Bloomsbury Group was experimenting with pure abstraction and painting everything but the kitchen sink.

Nor was the Blue Rider movement alone in its brevity. As with the Italian Futurists, who were also resisting tradition and convention, the shocking reality of the first world war overcame artistic flights of fancy. The men were of fighting age. Wladimir Burljuk, born in today’s Ukraine, was thought to have died on manoeuvres in Thessaloniki. August Macke, drafted into the German army, was killed in action. Marc volunteered for the German army and was fatally wounded at Verdun, dying aged 36 in 1916.

In their lifetimes, these men and women alike were inveterate travellers, and captions to the artworks at Tate Modern helpfully retrace the journeys of the often well-heeled artists: of Gabriele Münter, partner of Kandinsky, “born Germany, worked USA, Germany, France, Switzerland and Sweden”. Of Werefkin, “born Russian empire (now Russian Federation), worked Russian empire, Germany, Lithuania and Switzerland”.

These constant reminders of the artists’ big horizons chime with their interest in other cultures. Kandinsky, who came from an affluent family in the tea trade, went on an ethnographic expedition to Vologda, north-west Russia, which influenced his ideas about form and colour.

Werefkin, who grew up speaking Russian, Polish and Lithuanian, was given a pension by the tsar on the death of her father in his service. Münter and her sister Emmy inherited money derived from the US.

Münter and Kandinsky, who met as student and teacher in Munich in 1901, set up as a couple, despite his continuing marriage to his cousin Anna. They took the view that as they were outside society they might as well be out of the country, or at least the city, too, and they travelled widely.

The exhibition opens with photographs by Münter taken in Tunisia, where she recorded people and places that would have seemed otherworldly to the majority of less well-travelled observers. With her Kodak Bull’s Eye No 2, an early portable camera, she could capture a woman with an umbrella as well as any impressionist.

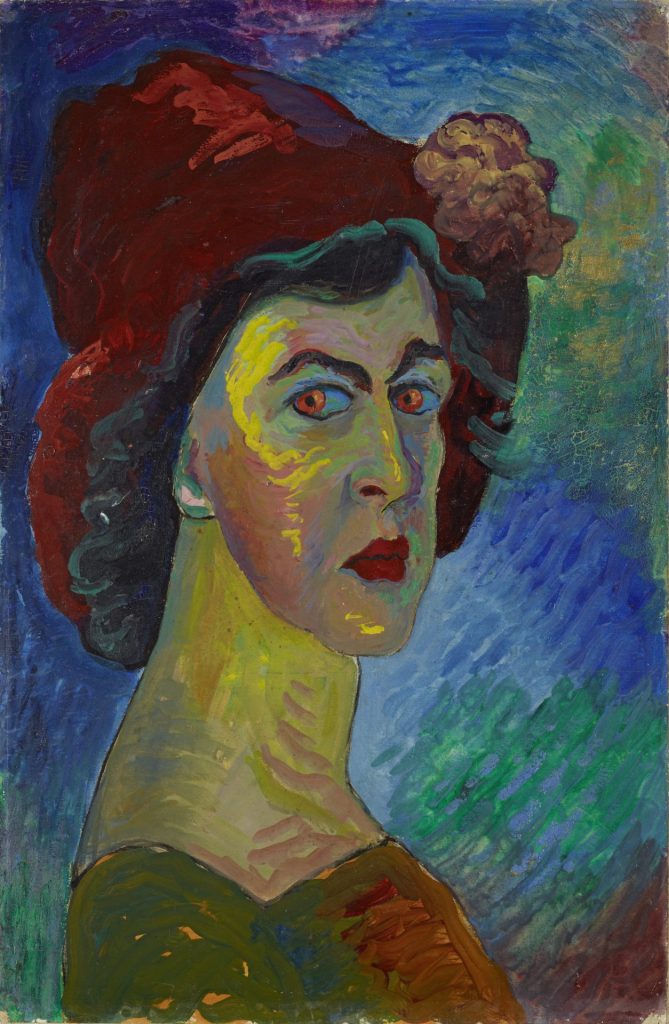

The livid colouring of Werefkin’s self-portrait could not be in starker contrast, but the two artists shared an unconventional approach to living. “I am not a man, I am not a woman, I am I,” she declared.

In her portrait of Alexander Sacharoff, the dancer wears a classically draped gown, luxuriantly bobbed hair, rouge, lipstick and a blissful smile. But it was with Jawlensky that she lived and worked (and Sacharoff married fellow dancer Clotilde von Derp, eventually opening a dance school with her in Rome).

Werefkin was a determined painter: after a riding accident in her 20s, she taught herself to paint with her left hand. But, as with other female artists before and since, she subordinated her career to Jawlensky’s over their 30-year relationship. It was Marc’s wife’s “fabulous coffee”, according to Kandinsky, that powered the meeting at which Blue Rider was given its name.

The men, meanwhile, were breaking new ground with the showstopping pictures that close this landmark exhibition, the first for 60 years dedicated to Blue Rider, and with 50 works never before seen in Britain, largely thanks to significant loans by Munich’s Lenbachhaus. The gallery was itself the beneficiary of Münter’s foresighted collecting (and hiding from the Nazis) of her contemporaries’ art.

With its mission to stifle the arts, this Brexit Tory government must be at least baffled, and probably annoyed, by the continuing generosity of loans between British and European galleries: the Lenbachhaus deal is partly born out of Tate’s recently lending to Munich 80 works for its first ever Turner exhibition.

While Marc’s much-loved and much-reproduced Blue Horse I is not among the loans, here is his formidable Tiger (1912), the yellow-eyed creature both curved and angular as it wheels round to glare at something seen or heard to its left, its bedding fierce shards of colour. How much warier it seems than the cattle that cavort in Cows, Red, Green, Yellow, a year earlier – further from the onset of war – in pastures blue, pink and white.

Kandinsky, too, immersed himself in the natural world. His Cow (1910) is unexpectedly white with yellow spots. She is being milked by a farmer with crimson hair, while her pink and blue companions graze in red pasture. In this bucolic scene, the only sweep of green is in, or possibly above, the blue hills.

But it is Impression III (Concert) that perhaps best sums up the aims of expressionism as articulated in a draft preface to the Blaue Reiter Almanac: “In our case, the principle of internationalism is the only one possible… The whole work, called art, knows no borders, or nations, only humanity.”

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider is at Tate Modern, London, until October 20