He kept the telephone.

A little after 3.30am on May 7, 1985 a cluster of petrol bombs was thrown through the windows of Bill Graham’s concert promotions headquarters on 11th Street in San Francisco, setting fire to the premises and causing $1m worth of damage.

Among the items destroyed were priceless memorabilia, concert posters, photographs, gold discs and musical instruments presented by the rock stars whose epic tours he put together.

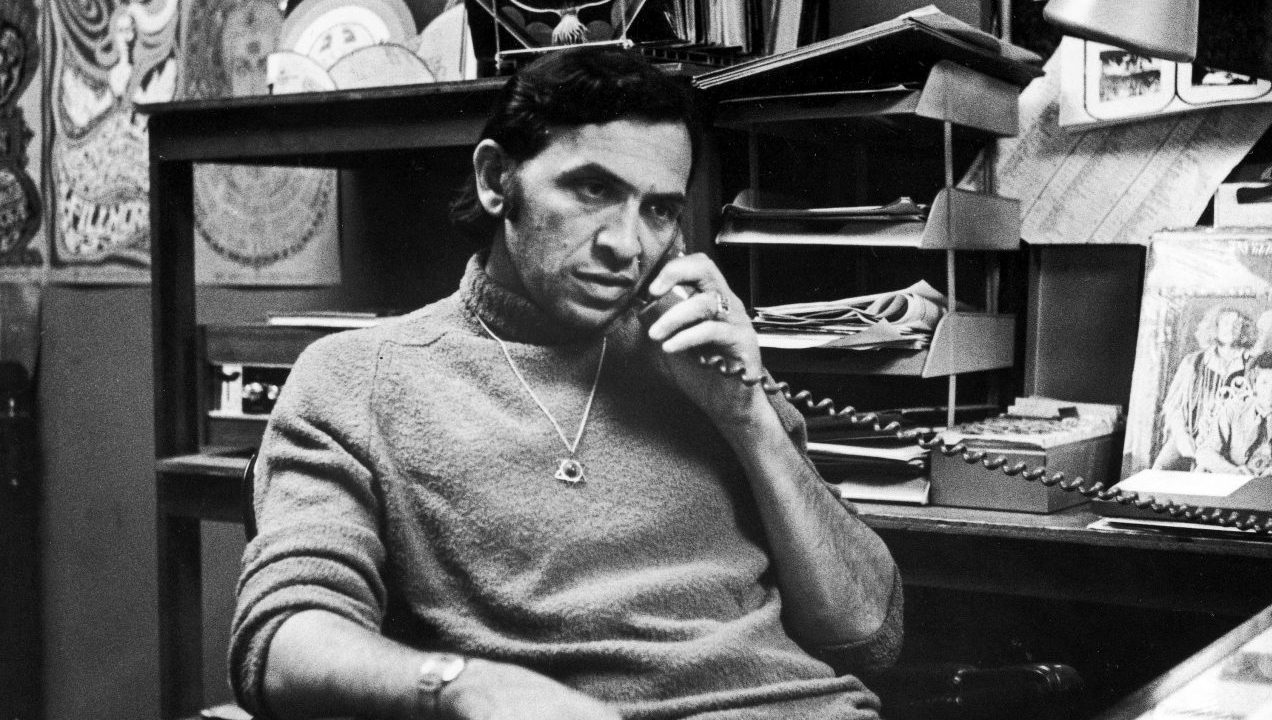

Of all the items he could have retrieved, Graham bent down and picked up a black office telephone, its receiver melted to the cradle, one side bulging and oozing enough to resemble a piece of surrealist art.

This was definitely Nazis, he thought to himself as he carried the telephone back out to the street. No question.

“There is no proof but there is a connection,” Graham later told a press conference. “There has to be a connection.”

A week earlier, Graham had organised a protest rally against US president Ronald Reagan visiting the military cemetery in Bitburg, West Germany, where members of the Waffen SS were buried. Five hundred people had turned out at short notice, many of them Holocaust survivors.

“Twenty years in business and never a single incident of violence,” said Graham. “This happened a week after the rally and a day after Bitburg. It obviously makes me wonder, and narrows down the possibilities.”

Graham had been one of the most high-profile critics of Reagan’s visit to Bitburg which was, he said: “one of the lowest, most immoral acts ever committed by a president. A more deplorable act I cannot imagine unless he were to bring back slavery.”

He was well-known for organising benefit concerts and tours for causes in which he believed, from Amnesty International to the dangers of crack cocaine. At the time of the fire he was immersed in putting together the Philadelphia Live Aid concert, for two months hence.

Bitburg, however, was different. Bitburg was personal.

“Bill Graham”, the impresario who hauled rock music out of the clubs and into arenas and stadiums, was just a convenient identity, a name adopted by a 12-year-old boy named Wulf Wolodia Grajonca when he opened the New York telephone directory and chose it at random. The name meant absolutely nothing to him, he said, but it was an opportunity to belong and a chance to start again.

Wulf Grajonca needed a new start because he was a Holocaust survivor.

He had to forge his own path almost from the day he was born in Berlin to Russian Jewish parents who had fled the pogroms. When Graham was two days old, his father Jacob was killed in an industrial accident leaving his mother Frieda a widow with six children to support. Forced into long days selling trinkets on the streets, something had to give and Graham and his youngest sister Tolla were placed in an orphanage in Auerbach.

As Nazi persecution of the Jews intensified, on July 4, 1939 Graham and Tolla were among a group of 39 Jewish children evacuated from the orphanage to France on a Kindertransport, eventually arriving at a chateau in Creuse before being moved on to Paris, only to find the Wehrmacht soon rolling across the border.

In the summer of 1941, sensing the increasing danger, Graham and Tolla set out on foot for Marseille. Tolla soon fell ill and had developed pneumonia by the time they reached Lyon. Graham was forced to leave her behind, only learning of her death much later.

At Marseille, Graham was placed on a ship to Portugal where he was then put on to the Serpa Pinto sailing from Lisbon to New York as one of the One Thousand Children, unaccompanied minors saved from the Holocaust and taken in by the United States. He arrived on September 24, 1941, exhausted, malnourished and weighing less than 25kg. At around the same time his mother and another sister were being murdered at Auschwitz.

Placed into foster care in the Bronx, he was taunted for his name and rudimentary English so it was not long before Wulf Grajonca became Bill Graham, complete with flawless New York accent.

That is why Reagan’s visit to Bitburg was personal. Having escaped the Holocaust, Graham had found sanctuary in the US and built not just a new life but a whole new identity. He had even served his adoptive nation in Korea, receiving the Bronze Star and a Purple Heart. America had been on the side of the good guys, they had got him out, saved him from the fate suffered by millions and he had repaid some of that debt in uniform. Yet here was the president bowing his head to men who had murdered his family.

Avant-garde mime theatre seems an unlikely career path for a Holocaust-surviving Korea veteran, but that was where Graham found himself in the mid-1960s, working as a gopher for the San Francisco Mime Troupe. In 1965 their leader was arrested during a performance and charged with obscenity, so Graham organised a concert to raise money for his defence, and the road to becoming the world’s leading concert promoter opened up before him.

By the late 1960s he had taken over the Fillmore West in San Francisco and the Fillmore East in New York and helped to launch the psychedelic rock scene, becoming closely associated with the Grateful Dead. At both venues he placed a barrel of apples at the door, a throwback to when he arrived in France and helped feed his fellow orphans by stealing apples from a neighbouring farm.

Perhaps that’s why, out of all the destroyed memories lying among the debris, he kept that telephone. Perhaps it represented a communication with that past. The Nazis had first cut him off from his family and his continent, now they were cutting off the past he made for himself in America. Yet he was still standing, picking his way again out of the debris left by the evil of fascism.

The fire exacerbated a disillusionment with the world he had helped to entertain but he remained optimistic about the future. Two weeks before his death in a helicopter crash, Graham had looked out across a teenage audience roaring along to Metallica at the Oakland Auditorium in California.

“There’s something going on out there and I’m not sure I understand it,” he said. “I look at them and wonder if they have a right to be that angry at such a young age. Maybe they have a toughness we didn’t. Wouldn’t it be something if we see some of the changes in the 90s that we dreamed of in the 60s?”