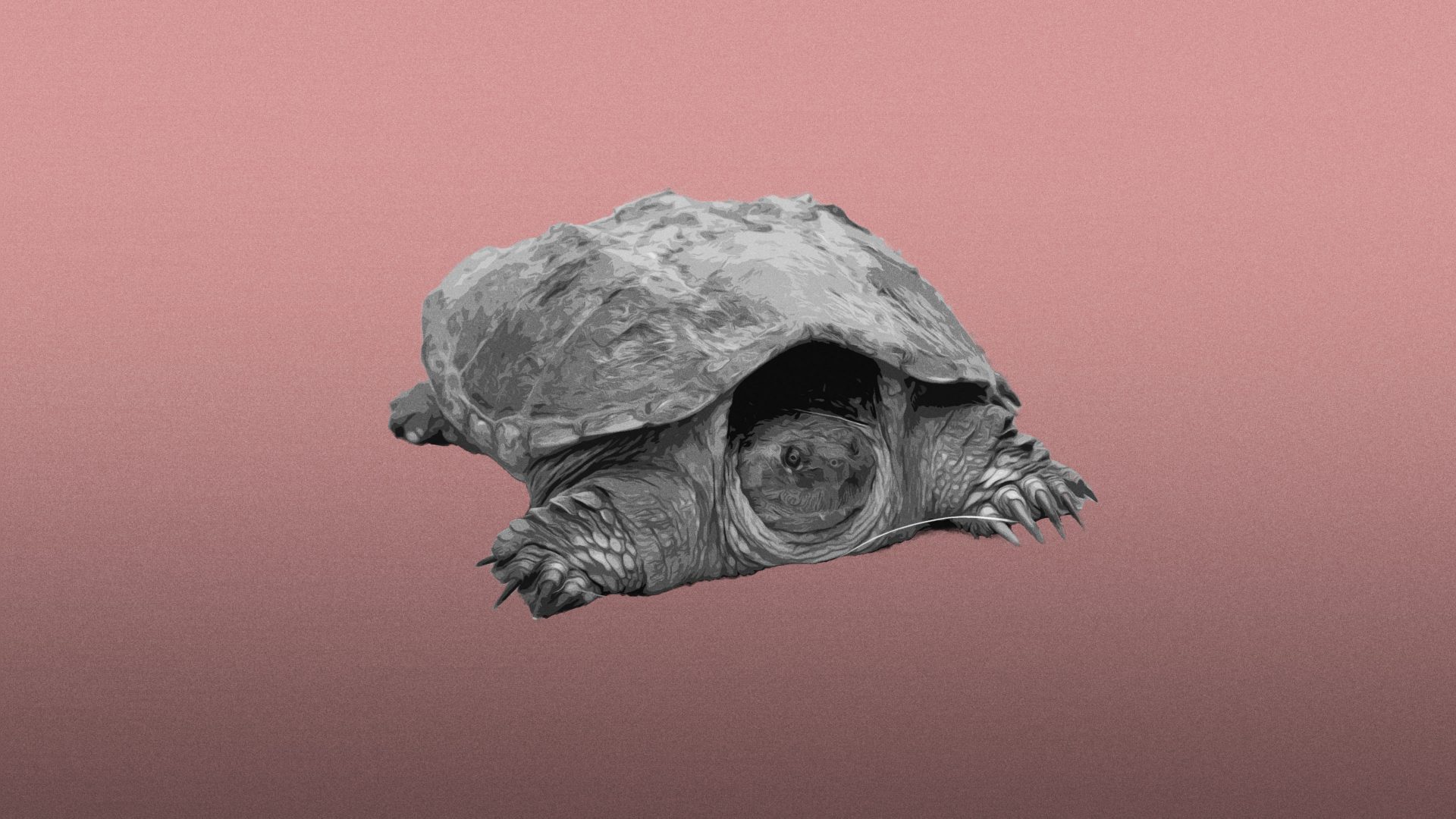

I was sunbathing in my garden on Saturday morning when, all of a sudden, I heard my neighbour Angela screaming at the top of her lungs. I rushed over to the fence separating our properties and saw in her orchard two huge, ugly-looking, grayish-green turtles with frightening beaks and claws.

“We tried to pick one up to put it back into the woods but it attacked us, nearly bit off our fingers. They are worse then vipers, aggressive: you try to move close and with a jerky movement of the neck they aim for your hand. We’ve called the police,” she said.

Twenty minutes later, the cops arrived along with an expert, a veterinary specialised in dealing with dangerous animals in domestic settings – like killer bears, wolves and foxes that venture into human habitats. Wearing a thick glove, he took the turtles from behind to avoid their eyes and potential bite, and carefully placed them in a cage. I have no idea where he took them.

I live in the countryside just north of Rome, in the Tiber Valley dotted with woods and streams. This atypical creature, which has been fittingly dubbed the “cannibal turtle” or the “biting turtle” is wildly reproducing. What is most scary is that it may be slow in walking but it’s as quick as lightning when it bites.

The veterinary tells us this crazy phenomenon is a side effect of climate change: “The recent flash floods and heavy rains that have struck Italy have led these turtles to leave the Tiber river tributaries and streams to seek shelter and food in the woods and nearby meadows where people live.”

There’s a little tributary stream that flows in the thick forest right below my patch of land. The turtles likely made their way uphill.

However, this big snapping turtle that can weigh up to 27kg is not an indigenous Roman species, it’s more the sort of reptile you would find in North America.

It’s an immigrant. Apparently, several years ago, people who loved wild turtles bought them as pets, and as it usually goes with little birds or exotic animals such as snakes and crocodiles, when they got fed up with them they dumped the turtles in the wilderness. The animals adapted, evolved into “Roman” and reproduced with other local species.

A few years ago I recall serpents, vipers and snakes being regularly caught inside homes, behind electric panels or underneath bathroom floor tiles. Then came the rainbow-coloured parrots breeding in the trees of Roman parks, likely escaped from zoos or amateur cages.

Now my countryside is regularly ravaged by wild boars that often sneak up to my plot at night looking for Jerusalem artichoke roots, and carnivorous turtles that are escaping from the flooded valley.

On Sunday I heard that other two turtles had been caught at another villa a few miles from mine. What a hellish weekend. Residents in my area have been alerted by local authorities that they must call the police at once if they spot one at their place, without attempting to touch it and risk a fingerless hand.

Shepherds are worried to take their sheep grazing out on the surrounding hills, while mothers no longer leave their little children out playing on the front porch but keep them indoors. Swimming-pool owners have nightmares that they might find themselves swimming with a biting turtle later this summer when temperatures will be scorching hot.

I’m scared for my baby Rottweiler every time he runs in the garden, and I constantly watch out for my toes when I walk in my flip flops.

It is not only Rome under attack. These turtles have been found also near the sea, along the Pontine Plains coast south of the capital, a very fertile place that used to be a marshland. It’s humid and dotted with watermelon and kiwi plantations that make great turtle lures.

As it happens, that is also where I always go to the beach each summer. I sort of feel persecuted.