On June 13, 1941, the Swedish freighter Annie Johnson pulled away from the quayside at Vladivostok in a frothing churn of brown water.

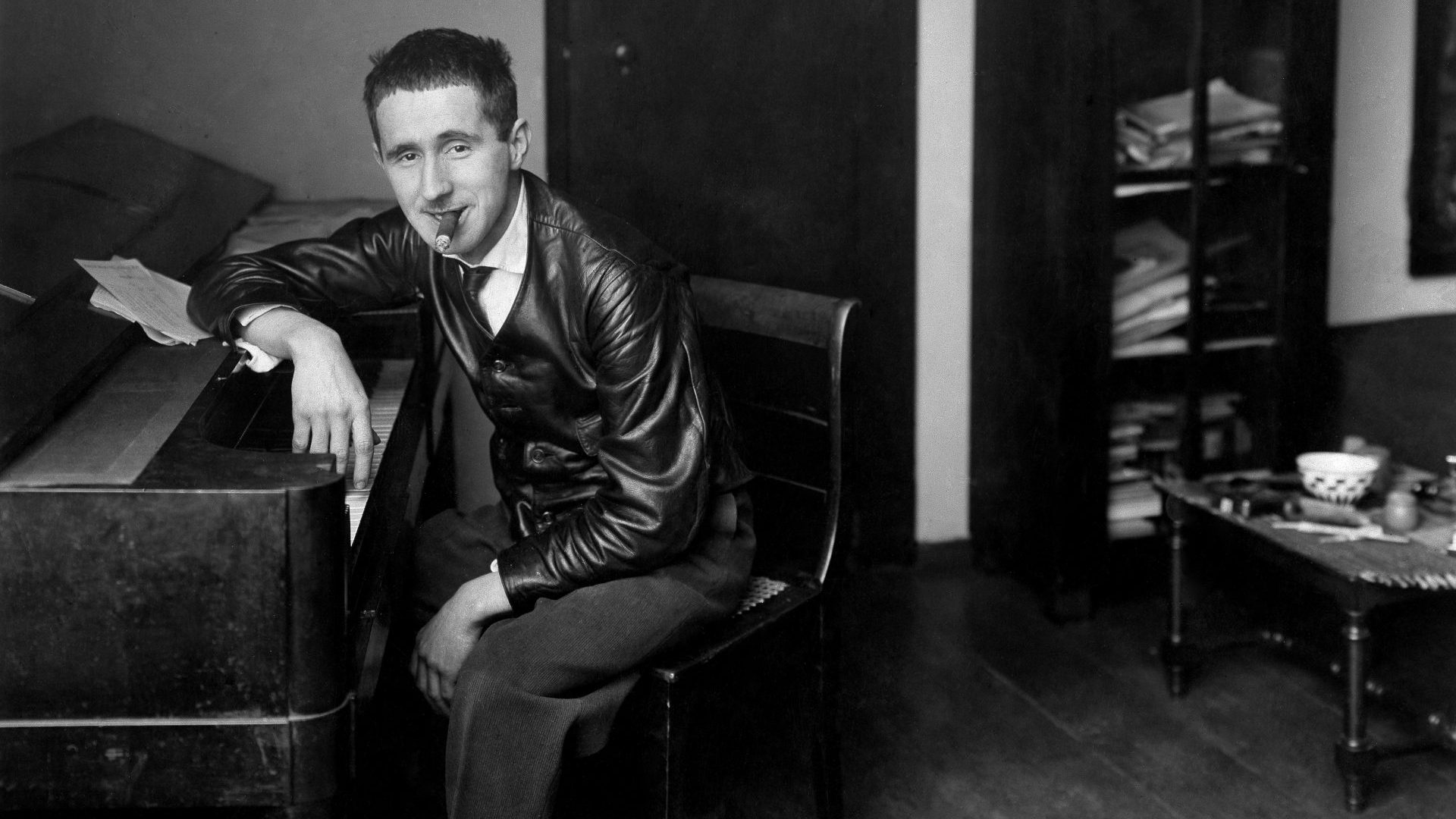

Among the 51 passengers heading south through the Sea of Japan bound for California were several bewildered refugees from Europe, including Bertolt Brecht and his wife, Helene Weigel, who were enduring what Brecht described as “the ninth year of the flight from Hitler”.

The 43-year-old poet and playwright’s future had never been less certain. The revocation of his German citizenship after his 1933 departure had left Brecht wandering the world stateless, relying on the generosity of governments and his literary reputation to secure refuge and safe passage.

Looking towards the horizon with the throbbing of the ship’s engines seeping into his bones, Brecht realised that almost a quarter of his life had been spent displaced. And now here he was, as far from everything he knew as it was possible to be, deeply apprehensive about the future.

“Not only have they robbed me of my house, my fishpond and my car,” he wrote of the Nazis, “they’ve also stolen my stage and my audience.”

Brecht had already revolutionised the theatre, particularly during a decade spent in Weimar Berlin. Left cold by the kind of immersive, naturalistic theatre popular at the time, believing that it made audiences “hang up their brains with their hats in the cloakroom”, Brecht demanded his audience avoid emotional involvement with the characters and scenarios playing out in front of them to better arrive at rational judgments and interpretations of the play’s core message.

His work sought to keep audiences aware they were in a theatre, not being transported to another realm by their imagination. His actors would change characters, plots would be suddenly disrupted and the performers address the audience directly to keep them alert to their surroundings, a technique he called the verfremdungseffekt.

When his first play Trommel in der Nacht opened in Munich in 1922, the renowned Berlin critic Herbert Ihering had heard enough about Brecht’s innovative potential to justify the long journey south.

“It is brutally sensual, melancholically tender,” he raved, marvelling at how “overnight this 24-year-old writer has changed the literary shape of Germany”.

Two years later, Brecht moved to Berlin and enjoyed his true creative and political awakening. He embedded himself at the city’s cultural heart and began to read Marx and Lenin, later writing “when I read Das Kapital I understood my plays”.

Marxism became the key conduit for his work, a philosophy that crystallised his vision for “epic theatre”, as it became known, his attempt to “deny the audience any kind of catharsis, forcing them instead to leave the theatre with a sense of being socially engaged”.

Brecht was always more prolific as a poet – a recent edition of his collected verse runs to 1,200 pages – and it was his poetry that led to a stormy but fruitful collaboration with the composer Kurt Weill. Weill had read Brecht’s poem cycle about the fictional city of Mahagonny and wrote to the poet suggesting a musical adaptation.

The innovative Mahagonny-Songspiel was first performed in a Baden-Baden boxing ring in 1927, which led in turn to Die Dreigroschenope, (The Threepenny Opera), Brecht and Weill’s homage to John Gay’s 1728 Beggar’s Opera that included what would become the jazz standard Mack the Knife.

First performed in 1928, The Threepenny Opera was a huge hit, enjoying a long run in Berlin that by January 1929 had spread to 19 towns and cities across Germany as well as Vienna, Budapest and Prague. In 1930 the pair unveiled a full operatic version of the Mahagonny project, Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, enraging the Nazis with its “contamination of the German opera house with Jewish and black influences” and prompting violent disruptions by brownshirt gangs at the premiere in Leipzig.

Inevitably, when Hitler came to power in 1933, Brecht was among those banned immediately as “degenerate”. He and Weigel left Berlin the morning after the Reichstag burned to the ground, a haze of smoke still in the air as their apartment was ransacked by police within hours of their departure.

They made first for Prague, then Vienna, until settling for the next six years in Denmark in a house offered to them by a friend of Weigel.

When the Germans invaded Denmark in 1939, Brecht was in Sweden, where he remained and began applying for American visas, but the subsequent fall of Norway ended any hope of fleeing west from Scandinavia. When their visas finally came through in 1941, Brecht and Weigel were in Finland, their only plausible route to America lying in a trek first across the USSR, then the Pacific.

With assistance from the Soviet Writers’ Union, in May 1941 Brecht, Weigel, their children and Grete Steffin, Brecht’s one-time lover, collaborator and secretary, who was dying of tuberculosis, took a train from Helsinki to Leningrad then travelled on to Moscow, where they were forced to leave the ailing Steffin to board the Trans-Siberian Express. Brecht was devastated by the news of Steffin’s death that reached him during the 10-day journey to Vladivostok.

Hence as the Annie Johnson made its way around the southern tip of Japan and turned east across the Pacific, a grieving Brecht gazed at the horizon with little sense of what might lay beyond it.

He certainly could not have predicted what was to come. His six years in America were unhappy, he never belonged, and he regarded the nation as culturally backward.

Describing himself as “a chrysanthemum in a coalmine” and dismissing California as “a shithouse”, he returned to Europe in 1947 the day after being called in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee on suspicion of being a communist.

After a year in Switzerland, Brecht finally settled in East Berlin, completing the circumnavigation of the world he had commenced when fleeing the city in 1933.

He had been offered the opportunity to form his influential Berliner Ensemble company, whose tour of Britain months after Brecht’s death in 1956 was a key catalyst in the foundation of both the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre.

Brecht lived through some of Europe’s darkest times, coming of age during the first world war and being cast adrift stateless in the world by events leading to the second, yet still produced some of the 20th century’s boldest, most influential and epoch-defining theatre.

As he wrote in his Svendborg Poems, written during his Danish exile, “In the dark times/Will there also be singing? Yes, there will also be singing/About the dark times.”