The summer after their wedding in December 1874, the artist Berthe Morisot and her husband of eight months, Eugène Manet, holidayed on the Isle of Wight. Among the many art shops in the north-coast resort of Ryde, Morisot spotted a work by Joshua Reynolds. She bought it, paying “a little less than two francs”. At around 16 shillings (80p) in English money, it was probably a good engraving or even a drawing, but the well-connected French painter was delighted with her acquisition.

Morisot’s affinity with British artists marks her out from the other French Impressionists, among them her brother-in-law Edouard Manet. After enjoying the spectacle of Cowes regatta, the couple’s extended honeymoon took in racing at Goodwood and a visit – did she take the waters? – to Tunbridge Wells, which, she notes is “a charming residence, about as far from London as Fontainebleau from Paris”. Worryingly for the spa town’s

residents, she adds “except…”. The rest of the text is illegible. She may not put a brushstroke wrong, but her writing was, by her own admission “atrocious”. In one of her many letters to her older sister, Edma Pontillon, she admits, “you will not be able to decipher much”.

This rapid penmanship is, in some ways, consistent with an energetic painting style that is celebrated in a new exhibition at the Dulwich Picture

Gallery in south London. The artist may well have visited the gallery with

its important permanent collection of, among other works, English and

French artists she revered. And it is likely that, while staying at another address a few doors away, she got to know the Wallace Collection in central

London, even though Eugène preferred messing around on the Thames to sightseeing in the capital.

Morisot was born into a comfortably-off family who had the imagination and the means to obtain privately the art tuition denied to women, excluded as they were from the premier art training institution, the École des Beaux-Arts. With Edma learning alongside her (and becoming a landscape artist and portraitist in her own right) Morisot’s tutors included the important landscape artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. But it would be portraiture and perceptive domestic scenes that would seal her reputation, not only as one of the top flight of Impressionists, but one with a distinctive style of her own.

Alongside her affection for the English portraitists, Reynolds, Gainsborough and George Romney, was an enthusiasm for the frothing fantasies of François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard. In the Wallace Collection, she would certainly have seen Fragonard’s most famous painting, The Swing, with its fizzing foliage and billowing skirts. So manifest in her own work was this artist’s influence that several observers considered her to be the Fragonard of her age.

This connection was encouraged not only by visible references to the earlier artist’s exuberant scenes, but because many believed Morisot to be a descendant of Fragonard. The misconception – for it is extremely unlikely to be true – was based on a

literal belief that she was his great-great-niece. This theory was backed up by the occasional accident of geography that brought their families close together, and by the Morisot family’s possession of a portrait of a relative painted by him.

It is the plight of many women artists to be endorsed by their similarity to another, male, artist. But it needs no comparison with Fragonard or any other painter to see Morisot’s unique talent. Partly out of circumstance, because a woman artist could not venture as a man could into the bars and theatres that made for interesting scenes, and partly inspired by the decorative domestic scenes of an earlier age, Morisot composed perceptive and unusual glimpses of life at home, in the garden and in society.

Her most frequent model was her daughter Julie, born four years after Berthe and Eugène’s marriage, and in years to come an artist herself. But

there is a poignancy about the affectionate pictures of the girl: Eugène died when Julie was 13, Morisot when she was 16.

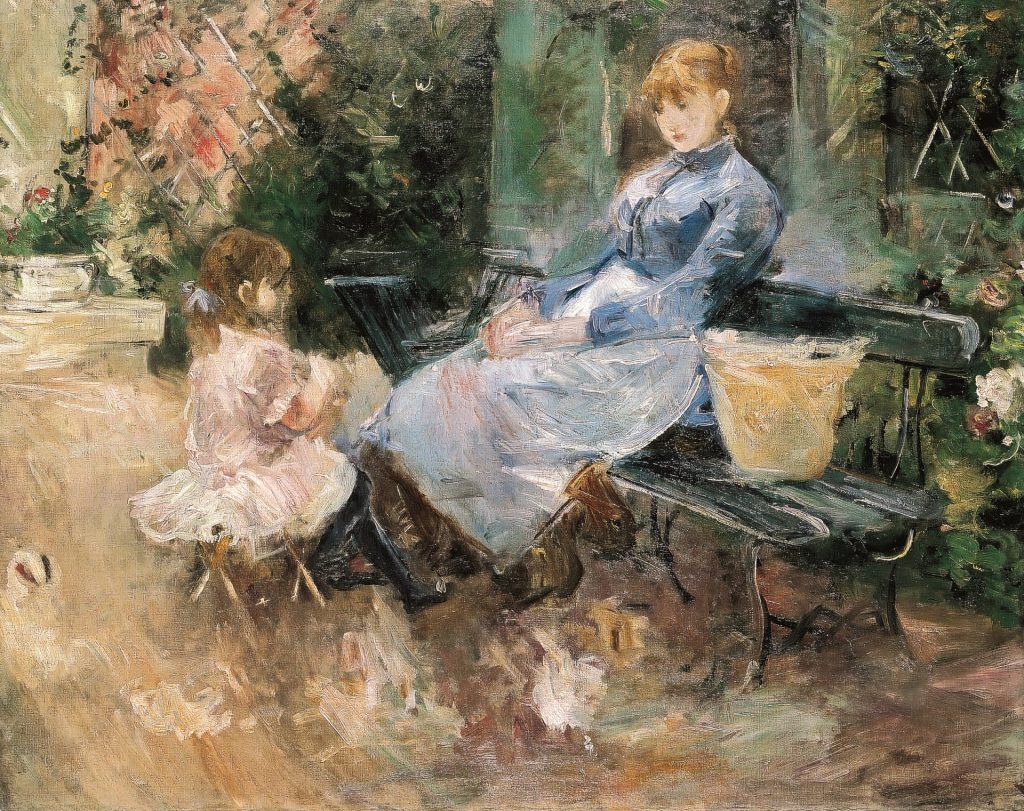

Julie appears as a small child with a serious, upturned face, addressing a nursemaid intently. Morisot, a mere observer, has to relinquish this precious moment of intimacy to her hired help, a bittersweet role for the working mother. Later, with her green eyes and green hair, Julie Manet and her Greyhound Laerte is not a sentimental child and pet picture, but a radical exploration of colour that anticipates expressionism.

Morisot’s sister was also her model. With a delicacy of palette that contrasts with the muscularity of vigorously loose brushwork, Young Woman Watering a Shrub depicts a young girl – it is Edma but it is also every amateur gardener – tending to her flowers. Seen from behind, she expertly lifts the layers of her skirts to one side, to keep them clean and dry, manoeuvring the water jug with her free left hand. Here is poise and practicality combined, domesticity and classicism in one moment.

The artist was painted by her brother-in-law Manet, and by Edma. Her own self-portrait shows a woman with a steady gaze, her hair scooped away from her face in a functional style. She notes in one of her revealing letters that on the Isle of Wight one day: “I had intended to work but it was too windy… I set out with my sack and portfolio, determined to make a watercolour on the spot, but when we got there I found the wind was frightful, my hat blew off, my hair got in my eyes. Eugène was in a bad humour as he always is when my hair is in disorder – and three hours after leaving we were back again at Globe Cottage.”

Eugène, it seems, could be easily displeased. Globe Cottage was attached to a hotel on the Parade in West Cowes, from where the honeymoon couple toured the island. The wife paints her husband seated in one of its windows, skewed round, an apparently reluctant model, more interested in watching the fashionable crowd outside. And fashionable it was.

Quitting the Isle of Wight suddenly – it seemed Eugène was out of sorts again – the couple made for London, where they met James Tissot. The artist had taken refuge in England during the Franco-Prussian war, and found light relief – and a considerable fortune – in painting decorous scenes of leisure and pleasure. Berthe wrote with enthusiasm to Edma: “Tissot tells me that during the regatta week at Cowes we saw the most fashionable society in England.”

Morisot may have had an eye for the unglamorous domestic scene, but she was accustomed from birth to a certain social status in life and was impressed by Tissot’s commercial success. To her mother, she wrote: “He sells for as much as 300,000 francs at a time… he complimented me, although he has probably never seen any of my work.” An attempt to contact a London dealer failed, and the British public was not considered ready for

Morisot’s work, subtler in subject matter and bolder in execution than Tissot’s as it was.

“At Ryde there are many shops, and even a picture dealer,” she writes. “I went in. He showed me watercolours by a painter who, I am told, is well

known; they sell for no less than 400 francs apiece – and they are frightful.

No feeling for nature – these people who live on the water do not even see

it. That has made me give up whatever illusions I had about the possibility of

success in England. In the whole shop, the only thing that was possible and

even pretty was by a Frenchman; but the dealer says that sort of thing does not sell.”

Perhaps the property-loving British would have approved of the artist’s pictures of her own homes. While she brought her own decorative talent to

bear in the couple’s doer-upper in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, inviting

Monet to cover one wall, she and Eugène had plans for even more gracious living in the Château de Mesnil, 50 kilometres south of Paris.

They bought the 17th-century mansion in 1891. The dovecote of their

project, gleaming with optimism against an inky woodland, straw-hatted Julie exploring up high, would no doubt have been the first of many pictures inspired by their new, rural, address. In the event, Eugène died within the year, aged 58.

Morisot’s importance within the much-loved Impressionist movement is borne out by her massive presence in the Paris gallery the Musée Marmottan Monet, which has loaned several works to Dulwich. In her short lifetime, she exhibited at all but one of the eight Impressionist exhibitions, from 1874 to 1886, alongside Monet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro and Caillebotte, only missing the fourth show, in 1879, shortly after Julie’s birth. She opened a door for women artists to follow through, among them her contemporary, the American-born painter Mary Cassatt. She outlived Morisot by 30 years.

Berthe Morisot, Shaping Impressionism is at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, until September 10