King Charles III finds himself with a burden greater than any that his mother faced. He is grappling to reassess the relevance of the institution he heads. At the same time, he faces a future in which his realm may well unravel. It’s a daunting test.

Now that Britain has been diminished by Brexit, the monarchy needs a new vision and with it, a high degree of competence. But while politicians have a good deal of latitude about where to find those qualities of leadership, the monarchy does not. We are stuck with Charles. Is he up to it?

It’s not just a question of how a king can adapt to change, or what the skills of kingship involve. A king and the leading members of the family are very limited in their freedom to act. Externally, the government decides where they go abroad and what they can say. Internally, they are guided by courtiers who are often Whitehall mandarins.

The scale of what Charles must navigate while simultaneously attempting to redefine himself, the monarchy and its relationship with the country was demonstrated by what happened to him a few days after he took the throne. Liz Truss, in an amazing but typical act of impertinence that would have been unthinkable with the Queen, cancelled his long-planned trip to the world climate summit in Egypt. Charles clawed back some authority by holding a Buckingham Palace reception for delegates on their way there, but his own frustration was clear. Dealing with climate change was not on Truss’s agenda and for that reason, the King was stopped from speaking on an issue for which he has a global reputation.

Next, the government decided that the King’s first state reception at Buckingham Palace for a foreign leader must be for Cyril Ramaphosa, the president of South Africa, where “state capture” has crippled public utilities. Ramaphosa is hardly a model for a Commonwealth head of state, but the hope was, apparently, that it might counter the increased influence in South Africa of Russia and China. It will take more than a meet-and-greet banquet to do that.

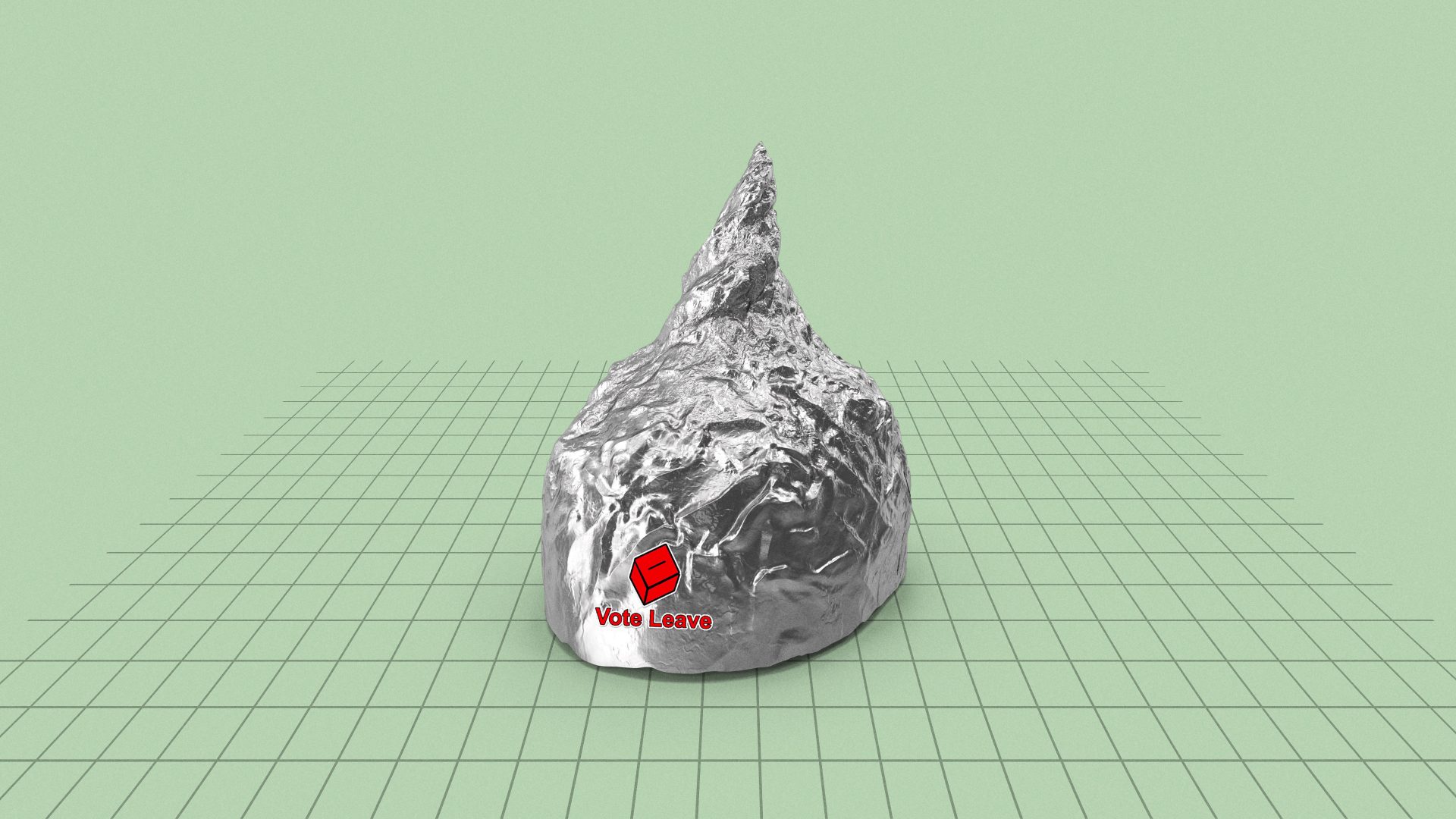

In his keenness to find a role, the King was next lured into a stunt that suggested he had entered transactional politics. Some spinmeister in the government thought it would be a good idea to attach the name “Windsor” to the deal being made to resolve Northern Ireland’s Brexit mess. The idea was that Unionists, loyal to the Crown, would be easier to win over if the deal bore a royal name.

But it was then decided that the so-called Windsor Framework should not be concluded on royal turf. Instead, the signing was done at a chain hotel three miles from Windsor Great Park and was announced at Windsor Guildhall, 100 metres from Windsor Castle. Ursula von der Leyen did get to take afternoon tea with the King at Windsor Castle, but Downing Street and the Palace were briefing against each other over whose idea this was. Reporters were told: “The King is pleased to meet any world leader if they are visiting Britain and it is the government’s advice that he should do so.”

It didn’t play well with the Unionists. Their spokesman, Sammy Wilson, said: “This is a cynical use, or abuse, of the King.” The Spectator warned that the monarch was entering “dangerous territory”. His mother would never have involved herself in such an overtly political situation.

The other working royals are carefully policed by the courtiers. They go where they are told and deliver pre-prepared words. Managing these performances is like running a theatrical company, as it involves attending to the frequently infantile vanities and rivalries of the stars, screening the locations and choosing the audience. But it is also much like micro-managing the image of a global, high-profile brand, albeit one with a very conservative culture.

That culture sustains a very particular kind of power structure, with a strong resistance to any change. Seen whole, the royal household is a sprawling and unique piece of bureaucratic machinery with many layers and the opportunity for those who run it to exercise significant executive powers, to preserve personal power and defend their siloes.

Even if Charles were a radical reformer, the prospect of changing this institution in a meaningful way would involve unwinding a status quo established by his mother. The Queen grew up believing that the sheer size of the royal family along with all its employees was a permanent and necessary part of the crown’s stature. Nothing about that would change while she was alive.

Now, the outlines of a leaner institution have to be drawn, by an untested King, at a time when the scale of the royal apparatus has never been more questionable. That’s not just an issue for the family and the government. It’s part of what the country itself has to decide about its future character – particularly what it is prepared to pay for its monarchy.

That begins with the King himself, and leads immediately on to the somewhat delicate question of Charles’s – and the Crown’s – wealth. Rather awkwardly, as most of his subjects have become poorer during the cost-of-living crisis, Charles has become steadily richer. A lot of that new wealth has come from the growth of what for decades he treated as his own division of “the Firm”, the Duchy of Cornwall. In the last decade before he became King, the value of the Duchy’s portfolio leapt by about 50%, demonstrating the gains available from traditional rentier capitalism: the Duchy’s 130,000 acres of prime land and property assets have performed in line with a booming market.

But there’s been entrepreneurial success, too, as Duchy Originals became, via Waitrose, the largest organic food and drink brand in the country, earning around £3.6m a year before taxes. Very few of the products are actually sourced from the Duchy itself. Most come from the same organic supply chain used by many other grocery brands. The only real value of this brand, identified by the portcullis logo, is its royal origin.

For the year ending March 31, 2022, Charles earned £21m from the Duchy, and also deducted millions in personal expenses for himself and Camilla. Although, while Prince of Wales, Charles paid the 45% top rate of income tax, the Duchy pays no corporation tax because, oddly, it is not considered a company – even though it is run on corporate lines with its own executives and a staff of more than 150. Charles also does not pay capital gains tax. These benefits have now passed to the new Prince of Wales, Prince William.

The King’s personal wealth is, though, just one part of the wealth of the monarchy – or, to be more exact, the sovereign wealth fund of the House of Windsor. Another part is what they use as their personal bank to fund their lifestyle: the Crown Estate. The name is misleading – the estate is not owned by the royals. Since 1760, when George III ceded control of it, it has been treated as a public asset run by commissioners for the government. The estate has a property portfolio now worth at least £16.5bn, including a large chunk of Mayfair.

The value of the estate’s holdings has enjoyed another huge boost, thanks to the convergence of the demand for renewable energy and one of its most archaic rights, going back to the Norman conquest – ownership of nearly all of the seabed encircling the UK, extending to the territorial limit of 12 nautical miles from the shore. That’s a lot of territory, even if it’s underwater.

In January, the Crown Estate licensed six new offshore wind farms in a deal worth £1bn a year – and that’s just the start. It was such a spectacular amount that the King announced that the profits would go not to him but to “the wider public good”, although there were no details about how that would actually work.

You would think that Charles, in particular, would take an interest in how well its managers act as stewards of the environment. The nation’s seabed ecosystems have been ravaged by development and overfishing. Yet when Welsh conservationists applied for permission to develop a five-acre test site to restore the health of the system by planting sea grass, to their amazement and annoyance they were charged £2,500 by the estate, a sum that made any future restoration unlikely.

All revenue from the Crown Estate flows first to the government, before 15% is allocated to the Sovereign Grant to fund the upkeep and expenses of the monarchy (this has been temporarily raised to 25% to cover the costs of renovating Buckingham Palace.) This arrangement originated in 2011, agreed to by George Osborne at the urging of Charles, who realised that, as it was linked to such a bundle of accumulating wealth, it would be far more lucrative than the civil list, which it replaced. Austerity did not affect the royal purse.

Charles has never welcomed outside scrutiny of royal wealth management. When challenged on his own personal wealth, he said: “I think it of absolute importance that the monarch should have a degree of financial independence from the state… I am not prepared to take on the position of sovereign on any other basis.”

Leaving aside the haughty tone, it is an assertion of his right to the personal lifestyle he feels entitled to, reflected in his foppish attention to clothes and the epicurean bloom on his cheeks. Instinctively, Charles is a plutocrat, and he lives in a plutocrat’s bubble. The Queen, though very rich, was not. Consequently, Charles’s version of a monarchy is beginning to look more and more like a plutocracy.

Royal wealth is accrued from huge unearned assets that have been soaring in value. This puts the Windsors in the same strata as other inheritors of large family fortunes. Real household disposable income in Britain has barely increased for 15 years. During that time the Sovereign Grant has grown from £30m to £86.3m.

Buckingham Palace encapsulates the state of the monarchy. Behind the façade is a decaying grand hotel. The wiring and plumbing are way below modern standards. Roofs leak, masonry crumbles. Before the 10-year renovation began, David Cameron and George Osborne agreed that £50m would be enough. In the end, Theresa May approved a final budget of £359m, an amount that will probably increase even further.

As her health declined, the Queen gave up living there – she always preferred Windsor anyway. Charles favours Clarence House. The official line is that he and Camilla will move down the road to the palace when work is completed in 2027. But the King has told people that the palace is no longer viable in the modern world as a royal residence. What does he propose to do with it?

This presents a fundamental test of whether he really has the resolve to reshape the monarchy. One thing he could do is give Britain its own Louvre. The royal art collection is one of the finest and most wide-ranging in the world, and yet one of the least seen – only about 0.1% is on display at any one time.

Charles I began the collection in the 17th century. He had a good eye for the great portraitists of the day – van Dyck, Rembrandt, Rubens – but that collection was broken up by Cromwell. The present collection was founded by the Georgian monarchs, who went on a buying spree across Europe, and it now includes more than 2,000 treasures, including everything from old masters to Indian manuscripts and priceless gems and jewels. Much of it is imperial loot.

The ownership of this trove is characteristically opaque: it is “held in trust” for the family and descendants – not the public. In a building with 775 rooms, as well as grand state rooms, there is plenty of space to create one of Europe’s great art galleries. At the same time, the King could open up the palace’s 39-acre private garden, by far the largest in London.

He should also put his money where his mouth is on the environment. Apart from running his James Bond vintage Aston Martin on fuel made from wine grapes and placing solar panels on the roof of Clarence House and some outbuildings at Highgrove, no environmental audit has ever been conducted on the energy sources of the royal properties.

The King’s first state visit abroad, to Paris, was cancelled at the last minute under circumstances that showed how risky it is to expose the face of a profligate monarchy to real-world events. The idea was to replay in every detail one of the Queen’s greatest hits, her visit to France in 1972, soon after Britain negotiated entry to the European Common Market. She was sent to Paris to make nice with the French, who had finally dropped their opposition to British entry. At a lavish banquet at Versailles, she told the French president, Georges Pompidou, “We may drive on different sides of the road, but we are going the same way.” It was a winning performance.

But as Paris was beset by demonstrations against President Macron’s proposed changes to the French retirement age, the idea of a glittering royal evening was unthinkable. Added to that was the problem that, instead of celebrating a new accord, Charles was going to Paris as the King of Brexit Britain, that obtuse offshore island that De Gaulle believed could never be truly European. Many in France remain baffled by why a once-powerful partner in the European project has been stricken low by an act of elective impoverishment. Charles would have given them few explanations on that point – at least, not in public.

In the end, Charles’s first overseas visit was to Germany – and it was judged a success. Most strikingly, he addressed the crowd of dignitaries, including the former chancellor, Angela Merkel, in German, and even dropped a few successful jokes. There is no doubt he is a good performer, in the right circumstances.

The Queen was different. While Charles is quite a well-defined character, she was unknowable. Her final appearance on the balcony of Buckingham Palace, in an emerald green coat and hat, at the conclusion of the Platinum Jubilee celebrations, produced a great, rolling roar of applause from her subjects who had packed the Mall. But, as she turned away from the crowds, a smaller and frailer figure with a stick in her left hand, she seemed to vacate more than just the balcony. The age she embodied was coming to an end.

The King approaches his coronation without any mystique. In any case, mystique would be of little use if it means placing a distance between the King and the people. To become an engaged and relevant partner in the struggle to establish a new sense of national purpose, Charles needs to listen more and unbend. So far, he appears a little tone-deaf.

The coronation plan includes an event called the Big Lunch “at which communities are invited to share food and fun together across the country”. That will be followed by “the Big Help Out”, which will “encourage people to try volunteering for themselves and join work being undertaken to support their areas”.

All of this reveals the bankruptcy of the palace planners. They are just rerunning the old Windsor playbook, issuing an invitation from above to feel good about the monarchy, without there being any actual royal contribution.

But the public is not so easily conned. A poll by Redfield & Wilton Strategies found that the age group normally most supportive of the monarchy, 55 and over, were actually the least likely to attend community parties. There is a growing sense that the coronation risks looking like a banquet next to a food bank. As Gordon Brown pointed out in a summary of rising destitution, there are 7.5m British households in fuel poverty, 14m living in damp or substandard housing, 400,000 children without a bed of their own and 271,000 homeless people at the latest count.

And a new YouGov poll has sent a clear message about the generational disconnect represented by the King: Kate (68% approval rating) and Prince William (67%) have displaced Charles, who is fourth in the rating (56%) – behind Anne (64%). Queen Camilla languishes at just 39%.

The coronation service in Westminster Abbey won’t have the same imperial trappings as Elizabeth II’s service in 1953. Social reform Windsor-style will be demonstrated by the fact that a prince’s former mistress can be crowned Queen Consort in a ceremony overseen by the Archbishop of Canterbury. They were wise enough to avoid planting the gigantic Koh-i-Noor diamond, an offensive piece of imperial grand larceny, in her crown, but Camilla’s headpiece will include three South African diamonds formerly worn as brooches by the King’s mother, worth around £50m.

The underlying risk of such a baroque enthroning pageant is that it can so easily verge on idolatry. It is clearly a service of worship – but who, exactly, in a secular democracy, is being worshipped? The last word on that should go to Thomas Paine, that great tutor of republics:

“And when a man seriously reflects on the idolatrous homage which is paid to the persons of kings, he need not wonder that the Almighty, ever jealous of his honour, should disapprove a form of government which so impiously invades the prerogative of Heaven.”

The chair of Duchy Originals has asked us to point out that it is a not-for-profit social enterprise that gifts all of its income after costs to charity