Of all the sectors of the British economy, you might have thought that the last one to be negatively affected by Brexit would be construction. After all, it is not as if you can import or export buildings.

But you would be wrong. Like so many aspects of what we do, the UK’s construction sector has been hit by Brexit – and hit hard.

Not only does construction employ – or used to employ – a huge number of skilled EU workers, but the raw materials that go into making a building are often imported. Doors, windows, tiles, wood, stone, insulation, electrical components and other vital products are imported into the UK, and 60% of those imported materials for the industry come from the EU. The fall in the value of the pound alone has led to far higher prices, but construction is also finding that many EU exporters have decided that the red tape, expense and bother of trading with the UK post-Brexit is no longer worth it. They have simply stopped supplying the Brits.

That problem has been made worse by a related issue: the pathetic attempt by the British government to change the testing and regulation of building materials by abandoning the Europe-wide CE scheme and introducing a UK-specific scheme called UKCA. This harebrained notion is damaging almost every sector of the economy, because the current system is well run, well understood and has been going for years. No one beyond the Brexiteers can see the reason or the need to change, re-test at huge expense and then end up with a system that is worse than the existing one.

Then we come to skills shortages. The construction industry is bedevilled by them, and even by a shortage of workers. The blunt fact is that around 40% of all workers in the construction industry are from the EU – in London the percentage is even higher. Many of them came to the UK as fully qualified plumbers, steel workers, electricians and bricklayers, and they have been much-needed as for years the UK has been unable to train enough locals to do this work.

Yet now, the government considers that such jobs are not “skilled” enough to be part of its skilled workers immigration scheme. This means many European construction workers who were here and helping our economy out pre-Covid, then went home before or during the pandemic to be with their families, cannot now come back.

The government does have an immigration scheme to deal with skill shortages, but like many other sectors, the building industry is finding that it is not fit for purpose. Some workers fall foul of the English language test, but more important is the need for businesses to sponsor workers from abroad. There are application fees, healthcare surcharges and a £1,250 bond to cover, and with 49% of the industry made up of the self-employed, most small builders have neither the bandwidth to fill in lots of forms nor the cash at hand to pay out for workers in advance. Of course, the EU workers can opt to do this themselves, but ask yourself this – would you fork out over £2,000 for the chance of a relatively low-paid job in a country that makes things difficult for you? You are much more likely to seek employment at home, or in a neighbouring EU country.

Rico Wojtulewicz, head of housing and planning policy at the National Federation of Builders, says the system just does not work. “There is no over-reliance on EU workers because they are cheap, it is simply a matter of necessity. The current system isn’t working, there are 80-90,000 construction companies but only 720 are registered as licensed sponsors of immigrants from the EU. It is too onerous, bureaucratic, and expensive.”

The industry is also hindered by this government’s seeming inability to reform the planning system and make it work quickly enough. As a result, many small and medium-sized building firms cannot guarantee that they will have a steady stream of work and so do not keep on permanent staff. Instead, they hire freelancers if and when they have enough work.

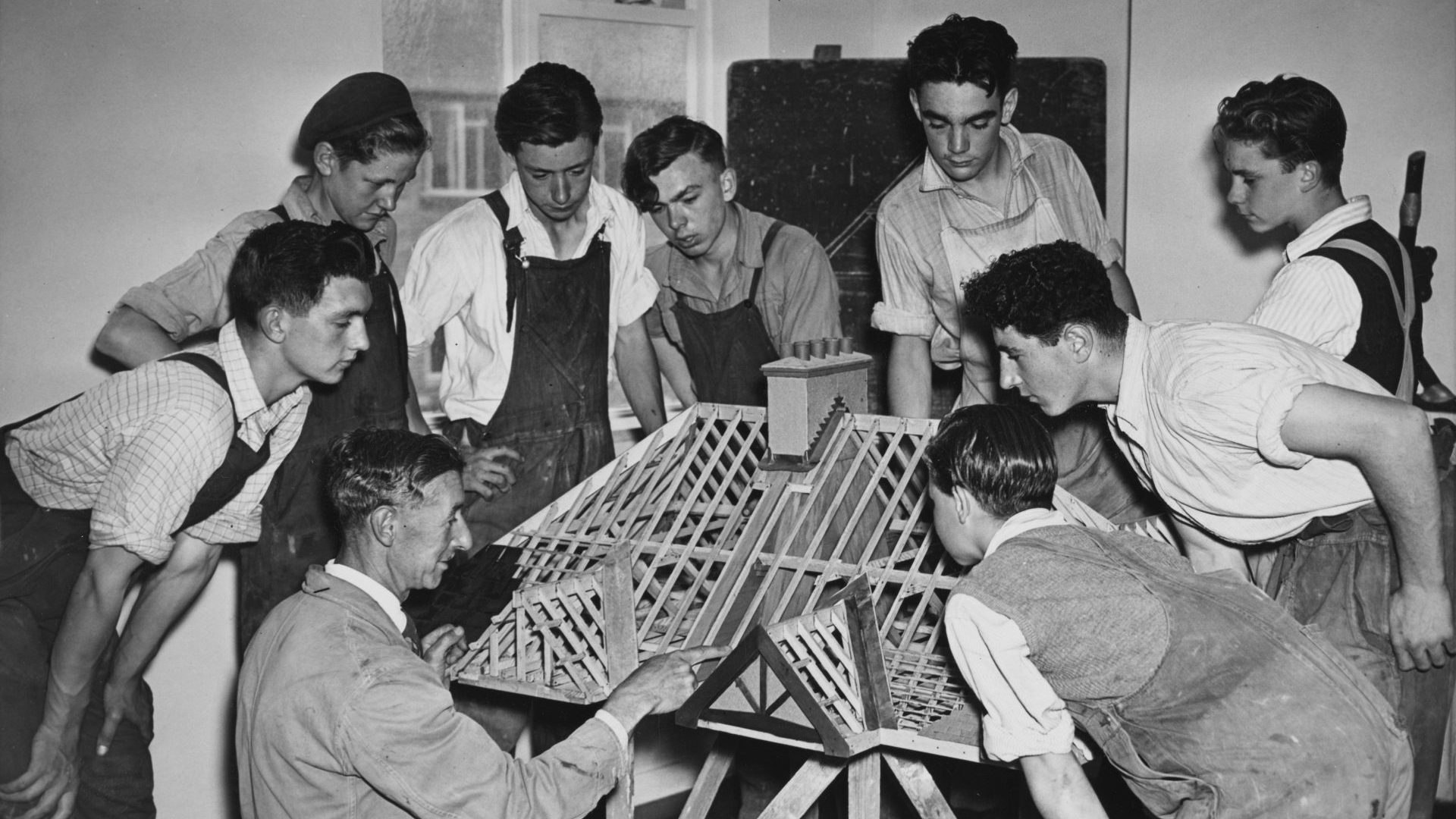

This fragmentation of the industry means many firms are just not large enough to train workers or take on apprentices. The industry as a whole is therefore not able to train enough British workers, even if it could find enough recruits. The complete failure of the reforms to the apprenticeship scheme in 2016 to increase the number of trainees in this and pretty much every other industry has added insult to injury; just reversing those so-called reforms would be of immense help on its own.

Rico and the NFB do, however, have a solution to this problem. They are suggesting that the government issue temporary visas of between three and five years for skilled EU workers, but with a catch. If a company hires such a worker “then you have to invest in a mirrored apprentice. That means you are benefiting from immigration but then investing in an apprentice here.”

So, you bring in a skilled worker and use the time gained and their skills to train a UK person to eventually take their place. It sounds like an excellent idea, so it will almost certainly never see the light of day under this government.

Nor does the industry agree that there is a big reservoir of British people who are economically inactive or have left the workforce and can just be tempted back to work in the sector. The Brexit ultras seem to think that there is a vast pool of labour available and that people just have to be forced back into the workplace to solve any skills shortages.

Suzannah Nichol, chief executive of the industry body Build UK, knows better. “People are just kidding themselves if they think these people are just going to turn around and step into a construction job and solve our skills challenges,” she told me. “Some are long-term sick, and the challenges in the NHS mean they cannot come to work, some have chosen to leave the workforce. We do want people to join our industry, however, construction jobs are more skilled than you think – can you go to someone who has chosen early retirement and say, come back to work but it will take three to four years to train you as an electrician or a plumber?” The answer is a resounding no.

On top of this, and adding to the burden of inflation, are the problems Brexit has imposed on the import of materials – a weaker pound, which means costs are higher, delays at the border and added red tape. And of course, there is the disastrous UKCA regulatory regime, which will involve firms re-testing many, if not all, products to meet UK standards even if they already meet the EU’s CE standard.

The Construction Leadership Council spells out the cost of going it alone when we could simply continue to align – were that not a dirty word to Brexiteers. They say: “The evidence makes clear that numerous common and essential products such as radiators, glass, passive fire protection, glues and sealants will be adversely affected by a lack of UK testing capability. The inability to certify radiators in the UK, for instance, could delay the construction of over 150,000 homes in a single year and will also delay the switch to low-carbon heating.”

The UKCA scheme has now been pushed back another two years, but even with that delay the industry doubts it will be ready in time. As such, it is becoming patently clear that EU suppliers to the UK market have little incentive to register their products under this new scheme. It is just another added cost to them, one that means they will have to produce each product to two different standards, one for the whole of the EEA and one for the UK. If the scheme goes ahead, it is one more powerful incentive to stop supplying the UK market altogether.

The construction industry feels as if it is banging its head against a brick wall. The sector has been growing strongly of late as it makes up for all that lost construction during Covid, but like the rest of the British economy it is now heading towards a slowdown; one made worse by the problems it sees coming down the track and a government that seems to be making things far worse by changing things for no good reason.

Border delays, red tape, an expensive and inflexible immigration system, skills shortages, and a new testing regime that serves no purpose. All are conspiring to handicap the industry and load expense on to firms.

Wojtulewicz has a plea for the government: “If they work don’t mess them around, if there are benefits keep them, if there are variations you need to make, make them. But don’t make this about short-term political expediency, because that is not good for Britain.”

That would be a solid foundation on which any sensible government could base its policies. Unfortunately, solid foundations and good sense don’t interest this one.