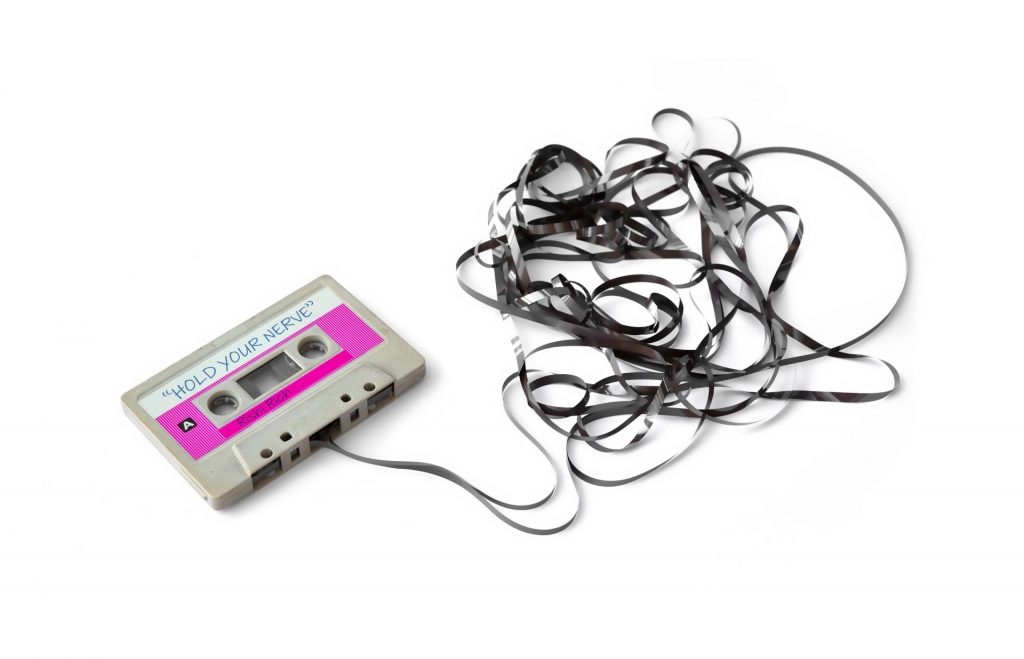

Confronted with soaring inflation and fast-rising interest rates, Rishi Sunak told the BBC last weekend that “we’ve got to hold our nerve, stick to the plan, and we will get through this”.

Holding nerve and toughing it out are meant to be core Tory attributes, although it is fair to ask who this “we” refers to. The public? The millions condemned to rocketing mortgage bills have little choice about holding their nerve. Paying twice as much as they expected was never part of their plan. Nor did the prime minister explain what it means to “get through it”. Perhaps he is cheerfully pointing to that distant day when interest rates fall again. Families may have only a few years of cancelled holidays and second jobs to endure.

But Sunak probably meant his own party. Panicked by the thought of a recession in an election year, it is Conservative backbenchers whose nerves are fraying the fastest. Calls for tax cuts, barely coded attacks on Bank of England independence, references to a mysterious Blob sabotaging everything – collectively, this is a party reaching for the political Mogadon of reality-denial.

There is a kernel of political logic to the prime minister’s plea for the party to keep its cool. Tough times are meant to suit the Conservatives. Their modern brand was forged in the bleak early 1980s, when the public was told there was no alternative, no turning back, no shortcut to the promised land. Margaret Thatcher famously toughed it out, and enough voters believed in the need for her bitter medicine for her to win re-election (albeit helped considerably by the Falklands conflict).

This is a Conservativism that David Cameron and George Osborne echoed during the austerity years, and again – in electoral terms – it worked. Voters accepted the near-term pain of cuts in exchange for a clean recovery from the shock of the financial crisis. The Labour Party, on the other hand, is more comfortable when the public coffers are full and its plans to improve society can be funded. Indeed, as a Lib Dem adviser to the Coalition government, I felt that the mid-parliament slowdown actually played into the Conservatives’ hands. A new election with the difficult times all in the past might have suited the opposition. Instead, there was enough of a deficit left to render unaffordable the sort of promises that Labour or the Lib Dems would have liked to offer. So the Conservative offer was: vote for us, again, because the tough times aren’t quite over. It was effective.

Today’s inflation-plagued economy provides no such silver lining for Conservative strategists. Our non-recovery from Covid and last year’s gas price spike may be bad news for a future Labour government, but won’t push people back into the Tory camp. But what began as an unavoidable consequence of Covid and Vladimir Putin has morphed into a spell of domestically driven inflation, and the UK is performing markedly worse than its European peers. The mutually reinforcing demands of workers, businessmen and financiers have driven spending to levels that make continuing or even accelerating price rises unavoidable. Britain is collectively demanding more from its economy than Britain can collectively supply, and inflation is the result. Labour is hammering home the message that the blame for high inflation can be laid at Sunak’s door – an attack rendered more potent by the prime minister’s oft-repeated pledge to halve it.

There is no way back to low inflation that is not painful. There was a time when the Bank of England might have lowered the temperature of the economy with just one tool, called “credibility”. This is a model of self-fulfilling expectations: since everyone knows that the Bank is determined to achieve 2% inflation, everyone should act like it was already so. By this magic, 2% is achieved without the Bank having to do much more than make some determined-sounding noises. (So confident was one governor in his mesmerising power that he once compared himself to the great Argentinian, Diego Maradona, running through a field of English defenders straight towards the goal.)

But this idea of an all-powerful, expectation-dominating central bank is long out of date. Like a weak-kneed supply teacher pleading with a rowdy class, the threats and urgings of the current governor, Andrew Bailey, are no longer believed. And the more the noise rises, the harsher the action that is needed to bring the class to heel. Given that a tax rise is off the table – can you imagine the reaction of Conservative backbenchers? – this has to mean higher rates. At its most recent meeting, the Bank raised them by a whopping 0.5%, and there may be more to come.

These are not the government’s direct decisions to make, but it has to own them regardless. There is much to admire in the determination of the chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, and Sunak to ignore all the pleas for leniency, including plenty from their own side. But do not expect the public to reward their resolve. While it is possible to make a virtue of difficult decisions brought about by actions out of your control, like overweening union power, a pandemic or war, few voters are going to blame anyone but the government for higher rates. The Conservatives are therefore forced to defend what economists might call an “induced recession”: the slowdown as a tool of economic management.

The 1980s echoes are not hard to see. This is the territory Thatcher occupied in 1980 when she asserted that “The Lady Is Not for Turning” – refusing to ease up on her hard-money policies despite unemployment shooting towards the scarcely believable figure of three million. Almost a decade later this tough attitude was echoed by her last chancellor, John Major, with “if it isn’t hurting, it isn’t working”. In both cases the government endured enormous unpopularity pushing Britain into a recession in order to wring inflation out of the economy; in both cases, inflation went away, and after a famous election victory there was a spell of spectacular growth.

Does this mean we face a return to the politics of the 1980s? The idea is incongruous at first glance. To an economist, this year’s inflationary surge is a rare point in common between that decade and this one. Britain began the 1980s dominated by manufacturing, powered by coal and oil, about to reap the rewards of its North Sea assets, and deepening its relationship with the European Community. Plagued by strikes – union leaders were household names – the defeat of unemployment was to become the challenge of the age. In real terms, wages had been growing strongly – too strongly, many felt. Inflation had been building for a dozen years, during which time governments had fitfully tried incomes policies and price caps to bring it under control. Shares were coming to the end of a long bear market. It was a good moment to be a worker in a secure job, an unpredictable period to be a capitalist, and an absolutely lousy time if you were a pensioner.

In almost every regard, today is different. The UK is running down its North Sea assets and has only the kernel of its manufacturing strength still intact. Unemployment is extremely low. Real wages, public sector in particular, are in a long-term slump. Capitalists and the old have done pretty well – share prices hit all-time highs even as the world shook off the after-effects of a global pandemic. Pensions have been protected when virtually nothing else has been. Inflation has returned seemingly out of nowhere. Up until 2021, deflationary conditions were so much the norm that most economists were caught off guard, not just the Bank’s. Most enrolled in “Team Transitory”, because in all of the recent data it flamed up only to fizzle out, like a sputtering campfire in a deflationary rainstorm.

It isn’t just the economics that is different. In many regards, Britain has been hugely improved by decades of steady reform and social progress. By many modern measures, the early 1980s was a rubbish time to be a British citizen. Hooliganisms and rioting were rife. Teen pregnancy was high and still rising. Homophobia and racism were common. Crime had increased all the way through the postwar period. Everywhere reeked of tobacco, and car engines spewed lead. Deaths on the roads were much higher – drunk driving was more prevalent, and seat belts did not become compulsory until 1983. Inner-city blight was a real problem (a worse one, I would say, than the sky-high rents we suffer from today).

Were it a straightforward question of who enjoyed the better lives, I would never swap the 1980s for today; I like music streaming, social liberalism and the internet, have no problem with high immigration, and really hate tobacco smoke, unemployment and casual racism. Much as I regret unaffordable housing, I think that particular injustice is outweighed by the blight of double-digit unemployment across countless towns in the north and Midlands. The Conservatives bang on about levelling up today, but might not need to, had so much industry not been levelled down in the 1980s.

For Britain, the postwar decades were an era of relative decline and missed opportunity. While France had les trentes glorieuses and the Italians il miracolo economico the British had lost an empire, and found a new nickname – “the sick man of Europe”. But in one crucial regard I would pick the 1980s over the 2020s. Britain was once a place that could imagine progress and drive towards it. We knew we could do better, and saw examples of this just across the Channel. Even in the UK, it was normal to expect each generation to be better off than the one before. Both sides of politics still believed this was within reach, if only the right policies could be enacted. The cocktail of difficult reforms put together by the Thatcher government had a point to them – the transformation of Britain into a more entrepreneurial, free-market and outward-looking place. This involved a heap of pain, but it wasn’t pain for its own sake. Of course, much of it was too harsh, and clumsily or even cruelly delivered, but it also contained positive ideas like the European single market and reforms that (under New Labour) did finally help to end the scourge of ever-rising inflation and unemployment. There was something for subsequent governments to build on.

The pain that “we” have to take today is of a different kind. Britons are now facing higher inflation and interest rates than in Germany, Italy, France or Spain because we have embarked upon a programme of regression. It will take years to disentangle all the factors, including the recovery from Covid and the Bank of England’s missteps. But I think stubborn inflation partly demonstrates how the motor of progress has been sabotaged. In the years since the Brexit referendum, investment has been weaker, the flow of immigrant labour seriously disrupted, and our supply chains crudely reconfigured. Brexit has led to a weaker economy and less revenue for the Treasury, and consequently under-resourced public services. Higher inflation is one way an economy displays its weakness. The metaphorical engine of the economy is beginning to sputter and smoke, and that squealing is the sound of us having to jam down the interest-rate brake harder than the rest.

Forty years ago, Britain led the world in economic reforms. Today, as Bidenomics propels the US into a manufacturing boom, we are left fretting about whether we have the funds to be a follower. Under Thatcher, sharply higher rates were part of a policy to drive the country into a better place. Today, they are just a painful acknowledgement that we have fallen into a worse one.

Giles Wilkes is a senior fellow at the Institute for Government thinktank

and was an adviser to Theresa May and Vince Cable