Dear Canese Jarboe, Fellow Cyborg Poet, Hi. This letter is my assistive device to write about reality. I don’t know how to write about reality for a general audience. But I know how to write a letter to you.

We both spent time on farms – you in Kansas and me in Alabama – so we know the seasons come and the seasons go. Likewise with words: they come and go, in and out of style. We’re both poets, so we have, somehow, dedicated our lives to words – and not just any words, but the precise words a poem calls for, the precise words a life calls for.

I don’t know if you identify as a cyborg. You could if you wanted. To be a cyborg, one has to be disabled. Maybe you’ve never thought of it that way. Historically, cyborgs have been disabled people going all the way back to Hephaestus. I’ve been saying this, introducing this identity, for more than a decade, yet I still get pushback. Most people think cyborgs are only creations in science fiction books and movies. But cyborgs are real: they are us. I’m still trying to convince people of that truth. That’s one condition of reality – it must be shared.

“Why are you going by the name ‘The Cyborg Jillian Weise’?” an interviewer asked me recently.

“Why are you going by ‘Steve’?” I wanted to reply. But I didn’t want to be rude.

“Don’t you think you are forcing it on people?” he asked.

“I guess your question,” I said, “presumes we already know the answer to who names who, and who gets to do the naming?”

I feel safe writing to you because you will not think I’m “forcing it” – that incorrigible it, my identity – on you. There’s no risk here, in this letter from one poet to another. We know how often our reality is defined from the outside.

It seems obvious that cyborgs are first and foremost disabled people, and yet I’m stuck inside this other reality, defined by nondisabled people, where I make an appeal for personhood. I’m so damn tired of this dynamic, where I am always the supplicant, always asking for a place at the table, the nondisabled table, and the nondisabled words. This isn’t even my table. It’s their table and their reality. They decide the terms:

1. The person’s body will be called “fake”. “That person has a fake leg,” for instance.

2. The person’s body will be owned by a multinational company.

3. The person’s body will be subject to warranty, dispute and reassessment for need.

So when I write about being a cyborg, I challenge reality. Some people react as if I’m trespassing and leading their favourite mare from the gate. Some people think it’s a joke or a phase. I can say, “I’m a cyborg,” but it doesn’t matter unless the word gains traction, becomes legible. Tired of playing defence for the word, I switched to offence and made up the word “tryborg,” a portmanteau for anyone “try”-ing to cy-“borg” a way into an identity that never belonged to them.

I count among us cyborgs nearly anyone with metal in or attached to our bodies – pacemakers, hearing aids, wheelchairs, canes, ventilators. Anyone who takes meds that jostle our brains? Very cyborg. Anyone who is disabled and integrates with tech? Very cyborg. Lila Moss at the Met Gala wearing an insulin pump and monitor? Very cyborg.

According to the Roman poet Horace, “As leaves fall in the season, so do words perish with old age, and new ones spring up and thrive.” At least that’s my translation of his work, and not a good one, since I don’t know Latin, but here I’ve planted the seed. Let us be cyborgs and free. Sappho’s version of reality was so scandalous that they set her poems on fire. One poem remains.

Canese, right now I’m thinking of your poem with the lines:

Could you get this bee out of my hair?

Could you just get this bee out of my hair?

Lately there’s been a bee in my hair, and it’s the title “Doctor”. It’s supposed to be an honorific, but I don’t know how it could be an honorific for me.

When I was born, the doctor said to my mother, “Don’t worry. If you want to get pregnant again, we will look for this. And abort it.” There’s that it again. I wish I did not know it.

With all that doctors have done to me, why would I want “Doctor” in front of my name?

Anyway, I took it. But it no longer fits. Now I go by “Cy. Jillian Weise”. Is that legible? To people outside you, outside me? I want the honorific “Cy” to indicate disability and honour. We have honorifics for all kinds of people, the married and unmarried, gendered and gender ambivalent, doctors and lawyers. Why not an honorific for disabled reality?

Once you earn the PhD in English, I won’t be surprised if you go by “Dr. Canese Jarboe”. I’m not prescribing a new honorific for every cyborg, every disabled person. It would be bombastic for me to suggest we drop “Dr” as a title. Besides, many people are the first in their families to achieve the degree. I am the first in my family.

And yet when I walk into my classroom and write “Cy. Jillian Weise” on the board, I feel alive and out of the bramble of their reality. That bee is out of my hair. My name doesn’t sting any more.

Sincerely,

Cy. Jillian Weise

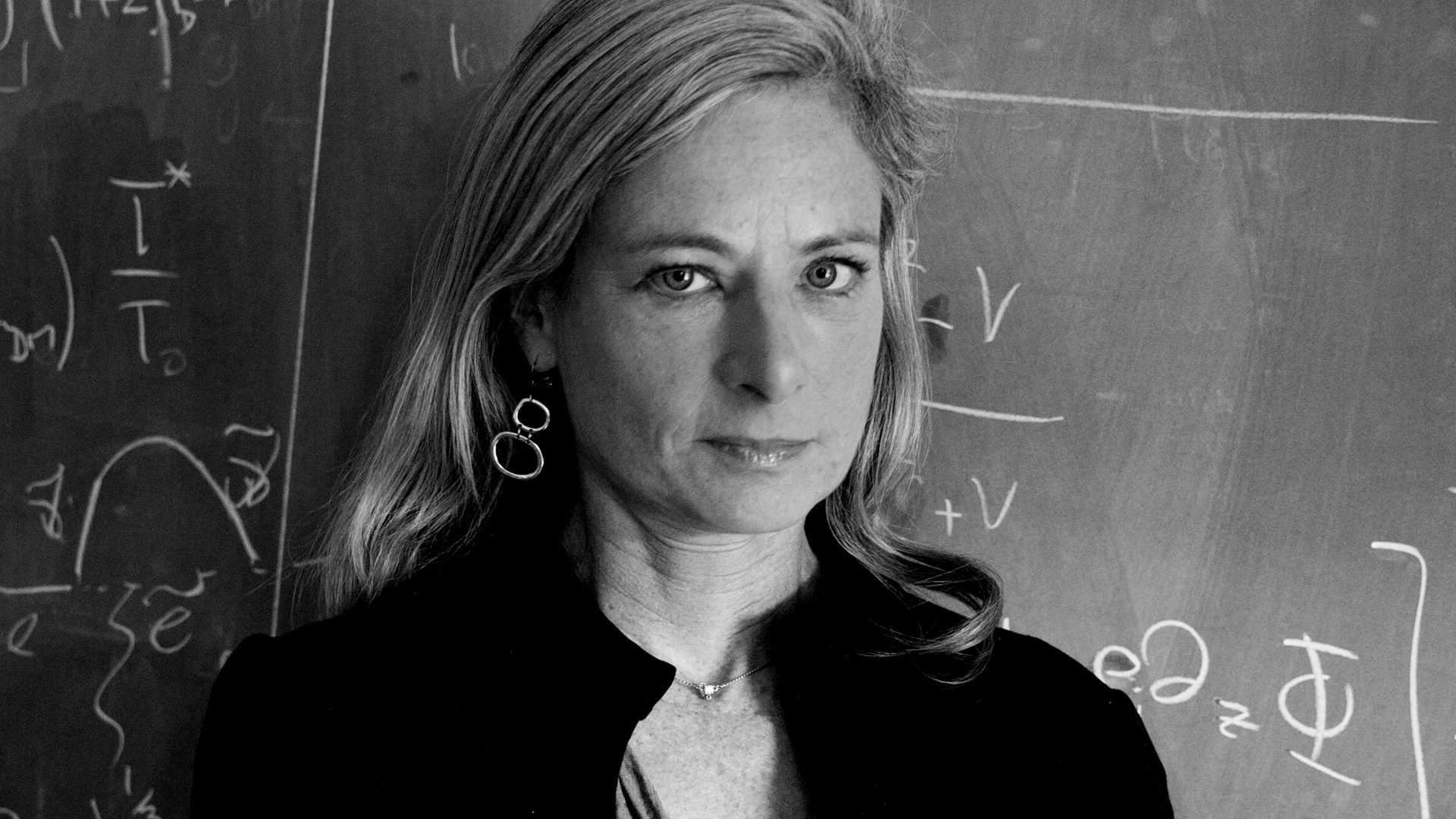

The Cyborg Jillian Weise is a poet, performance artist and disability rights activist © The New York Times Company and Cy. Jillian Weise