Britain is now an anti-Brexit country. The polls confirm this; but it is also true in a politically more telling sense. The change in the national mood has not required anyone to change sides. The power of remorseless demographics has been enough to do the job on its own.

In the past seven years, more than four million people have died. They were mostly older voters who backed Leave by two-to-one. Over the same period, almost five million people have reached voting age, and they overwhelmingly want Britain to be in the European Union.

The combined effect of these two trends has been big enough to wipe out the 1.3 million Leave majority in 2016, and replace it with a 1.6 million majority for Remain. (This estimate takes full account of the fact that older voters turn out in much larger numbers than the under-25s.) If the referendum were being held today, Remain would defeat Leave by 17 million to 15.4 million – again, assuming nobody has switched sides.

Four years ago, when I first wrote about the demographics of Brexit, I was challenged by Leave supporters who argued that, as there was such a strong link between age and attitudes to Brexit, we should expect many Remainers to become more pro-Brexit as they grew older.

Nice try, Leavers, but that’s not what has happened. Deltapoll’s latest research shows that, far from becoming more Eurosceptic, voters have drifted in the opposite direction. More have switched from Leave to Remain than from Remain to Leave. The difference isn’t great; but the figures are sufficiently consistent over time, and confirmed by other pollsters, for us to be sure that Remain’s overall lead has increased still further, adding to the impact of demographic change.

The latest Poll of Polls reported by the National Centre for Social Research shows that a referendum held today would produce a decisive 56-44% majority for rejoining the EU rather than staying out.

Let us unravel the story of how the national mood has evolved – and the clues this story gives us about where we go from here.

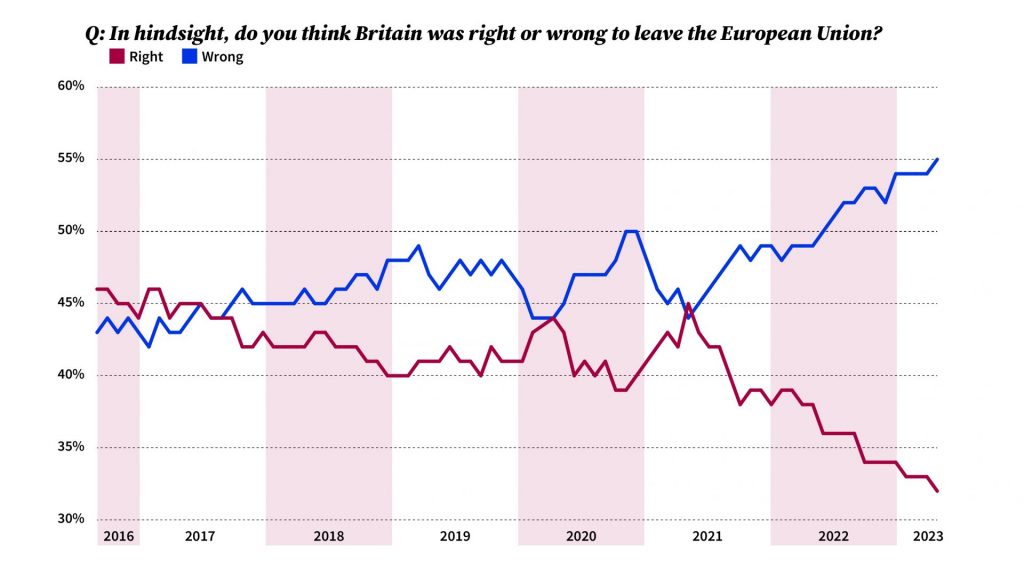

Our most useful guide to the ebbs and flows of public opinion comes from YouGov. Starting just six weeks after the referendum, it has frequently asked people whether “Britain was right or wrong to leave the European Union”. For the first year, their figures were close to the referendum result, with those saying “right” usually just outnumbering those saying “wrong”.

After that, buyer’s remorse began to set in, with “wrong” moving into a clear but not overwhelming lead, generally of 5-10%. Twice, however, events pulled the figures back to level-pegging. The first was in the aftermath of the 2019 election, the vote to “get Brexit done”, and the UK’s actual departure from the EU in January 2020. The second was in the spring of 2021, when Boris Johnson was claiming the credit for opening up normal life after the nightmare of Covid.

Since then, the trend has been one way – two years of steadily more people saying we were wrong to leave the EU. By the end of 2021, the gap between the two sides reached double figures. A year later it was touching 20 points. It is now hovering around 25 points. These days, for every 10 voters who still favour Brexit, 16 say it was a mistake.

Drilling down into YouGov’s latest figures, we find that just 65% of Leave voters now say Britain was right to quit the EU. The other 35% either say it was wrong (22%, or more than three million people) or don’t know (13%, or almost two million). In contrast, Remain voters line up solidly behind the view that Brexit was a mistake. As many as 91% still think this.

After decades of poll-watching, I cannot think of another major controversy that divides the country down the middle, where so many on one side of the argument have stayed so firm for so long.

If anything, the figures for Leave voters understate their buyer’s remorse. Only 20% of them think “Brexit has been more of a success or more of a failure” (YouGov), while just 23% of them reckon that Brexit has raised living standards (Deltapoll). Both surveys find that more Leave voters give Brexit the thumbs down than the thumbs up.

We can go further. Although the proportion of Leave voters who say Brexit has been a success is just one in five, the number who can identify a way in which they have personally benefited is even lower. According to Deltapoll, a mere 12% of Leave voters say they can – but when asked to name one, the figure falls to just 9%.

Seven years ago, we were promised that Brexit would save the UK £350m a week in payments to Brussels, money that could go to the NHS. Seven years later, out of Deltapoll’s sample of more than 2,600, just 16 – that’s people, NOT per cent – spontaneously offer “not giving money to the EU” as a major benefit. A dog may be for life, not just for Christmas; in contrast, a campaign lie is for the moment, not posterity.

A word of caution. Most economists, including the government’s own Office for Budget Responsibility, agree that Brexit has harmed the economy. But prosperity has also been damaged by Covid (which gave us a short but very sharp recession) and the war in Ukraine (which has pushed up inflation). It is likely that Brexit’s reputation has suffered some collateral damage from these events. When a government presides over rapidly rising prices and sharply falling living standards, then many voters will find fault with all of its policies.

Without Covid or the war, the government might be more popular and Brexit less unpopular. That doesn’t mean that YouGov’s right-wrong figures would be reversed, just that the majority saying Brexit was wrong might not be so large.

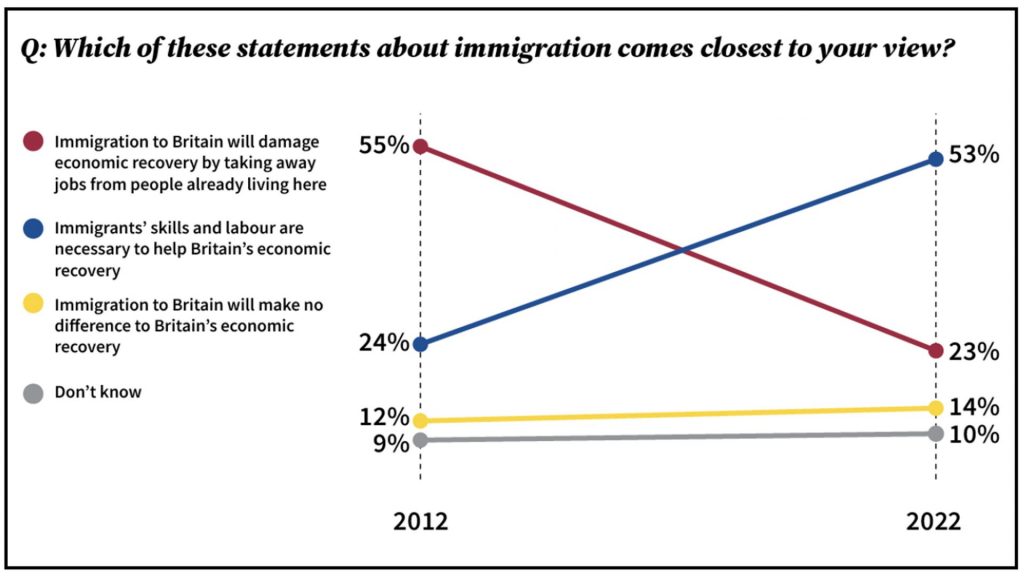

No such caveat applies to the other huge contributor to Brexit’s victory seven years ago, or the transformation of public attitudes since then. Immigration played a huge part in the referendum campaign – remember Nigel Farage’s “Breaking Point” posters, purporting to show a long line of immigrants and warning of Britain being overrun if Turkey joined the EU. Polling by Ipsos ahead of the referendum showed immigration leaping ahead of any other issue as the most important facing Britain.

This reflected, among other things, a culture-war triumph of right wing lies over progressive tolerance. This is clear from one of the YouGov polls that shocked me most in my 15 years with the company. I wanted to test views about so-called “welfare tourism” – the assertion that Europeans were settling in Britain in large numbers not to work but to claim unemployment benefits. In December 2013, we asked:

Q. According to official statistics, around 2.3 million people living in Britain are immigrants from the rest of the European Union. How many of them do you think are currently claiming the main unemployment benefit, the Job Seeker’s Allowance?

Among all respondents, the median figure was 400,000. Among Ukip supporters, it was twice that – 800,000. The true figure? Just 60,000. Crisis? What crisis?

Bear that in mind when we look at public attitudes to immigration these days:

The proportion of people who tell Ipsos that immigration is one of the most important issues facing Britain today is now just 17%.

Far fewer people nowadays think immigration damages economic recovery “by taking away jobs from people already living here”. Ipsos finds that it has more than halved since 2012 from 55% to 23%. The number saying “immigrants’ skills and labour are necessary to help Britain’s economic recovery” has more than doubled, from 24% to 53%.

Support for immigration from the EU is even higher, as long as “welfare tourism” is removed as a factor. Two recent polls by different companies asking the question differently produce similar results. According to Redfield & Wilton, by 53-15% we would allow “EU citizens to freely travel, study, work and immigrate to the UK” if UK citizens had the same rights within the EU. Deltapoll found that 66% agreed that EU citizens should have “the right to live in Britain, provided they can show they have a job to go to”. Just 13% rejected this proposal. Even Leave voters support this by almost three-to-one.

It should be remembered that the EU’s freedom of movement rules are economic in origin. They are part of the package of single market rules that set out the rights of goods, investment and workers (not non-workers) to move freely across borders. A British government that signed up to all this, and could persuade voters that “welfare tourism” was a non-issue, need have little fear of the electorate.

Taken together, the data from the real world and from the polls, about both the economy and immigration, suggest that a future government that wished to negotiate a return to the EU’s single market (or something with a different name but akin to it in practice) would gain more votes than it lost. To be sure, if it announced a policy that failed to deliver the promised benefits, it would suffer. But that applies to any big decision a government makes.

Does all this mean that the next government should go further? If it is to rejoin the single market, why not go the whole hog and reverse Brexit altogether – not least so that we can have our say in EU rules that affect us? The logic is clear and, as we have seen, Britain has become an anti-Brexit country.

However, a huge “if” lurks around the corner. If we could be certain that the day after a referendum we would be transported back the next day to full membership of the EU on the same terms that we used to enjoy, there is a high chance that most voters would back it.

Sadly, this is not on offer. Negotiations to rejoin the EU would be tough and lengthy. Britain might have difficulty regaining the rebate it used to enjoy. And other countries would surely question its pre-2016 opt-outs, not least the UK keeping the pound and remaining outside the eurozone.

Even if the British government succeeded in reviving the rebate and the opt-outs, a price might have to be paid elsewhere in the talks. Nobody could be certain either that the negotiations would succeed, or that public support for reversing Brexit would be sustained.

Another poll confirms the case for caution, albeit tinged with optimism. Opinium regularly asks a question that offers four options – not just a binary in-out choice. Its latest survey finds that 36% want Britain to rejoin the EU, while a further 25% prefer to stay out but with a closer relationship. So a clear majority, 61%, wants a more pro-EU future (and they include as many as 38% of people who voted Leave). Far fewer prefer the status quo (17%) or a more distant relationship (12%). In short, there is a big public appetite for Britain starting to journey back to Brussels, but not yet sufficiently solid agreement on the final destination.

This is not an argument for abandoning the dream of rejoining the EU. It is, however, an argument for acknowledging how tricky it will be to reach that goal. Each stage of the journey must be planned with care, not least to keep the electorate on board. The polling evidence supports the case for a first stage that is bold but specific: a full restoration of frictionless trade, including freedom of movement for workers. That would undo much, though not all, of the damage Brexit has inflicted.

Done openly and honestly, it would appeal to most voters. It would revive Britain’s prosperity and could whet the public’s appetite for travelling further towards restoring Britain’s place at the heart of Europe.

If, instead, we do not even start that journey… Dear reader, I leave the rest of that sentence to you.