Rishi Sunak is a young prime minister. At 42, he’s just a smidgeon too old to qualify as the UK’s first millennial PM, but he can certainly claim to have at best hazy memories of the 1990s – he was just 10 years old when John Major became prime minister, and was still only 11 at the time of Major’s shock win at the 1992 election.

Having a poor memory of the 1990s is the only way to explain why No 10 is briefing out their hopes that Sunak is the new Major, a man who can pull off another 1992-style victory.

The version of events in their head must roughly be this: larger-than-life leader with a strong personal mandate becomes wildly unpopular and is toppled by their own party, leaving the party looking for an emollient new leader who can clean up some of the mess.

In the 1990s, this was the (relatively) young 47-year-old John Major, who came in with personal popularity above that of his party, secured the “best” of Thatcher’s legacy, defused a few landmines, and led the party to a close-but-unexpected fourth term victory – against widespread media and polling expectations of a Labour win.

If that’s all you know of the UK politics of the 1990s, you can see why this is a story you’d be rushing to tell. It lets the Conservatives say: “OK, we know things look bad, but we’ve come back from this before”. The problem is that in reality the story fails on two different levels: the first is to look at what the above narrative leaves out from the 1990s – and the second is to note that Sunak’s position is even worse than that inherited by John Major.

Major had the advantage of a simple succession from a leader he played no obvious role in toppling – on the fateful few days of Thatcher’s defenestration, Major was away from the action having had surgery on his wisdom teeth. This let him come in as PM relatively cleanly, and as his predecessor’s favourite for the job (even if she then became a nightmare for him from the back benches).

Major also had a wildly unpopular policy that he could, and did, reverse course on. The community charge – much better known as the poll tax – had turned into a political disaster, which in turn (due to non-payment) became a policy disaster. Major scrapped it, replacing it with council tax in the form we still have today.

There was also an easy foreign policy win to be had. Much is made of the extent to which Thatcher benefited from the surprise victory of the Falklands War, but much less remarked upon is how Major had a short, successful overseas conflict – from a political point of view – in the Gulf War, which repelled the forces of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq from neighbouring Kuwait.

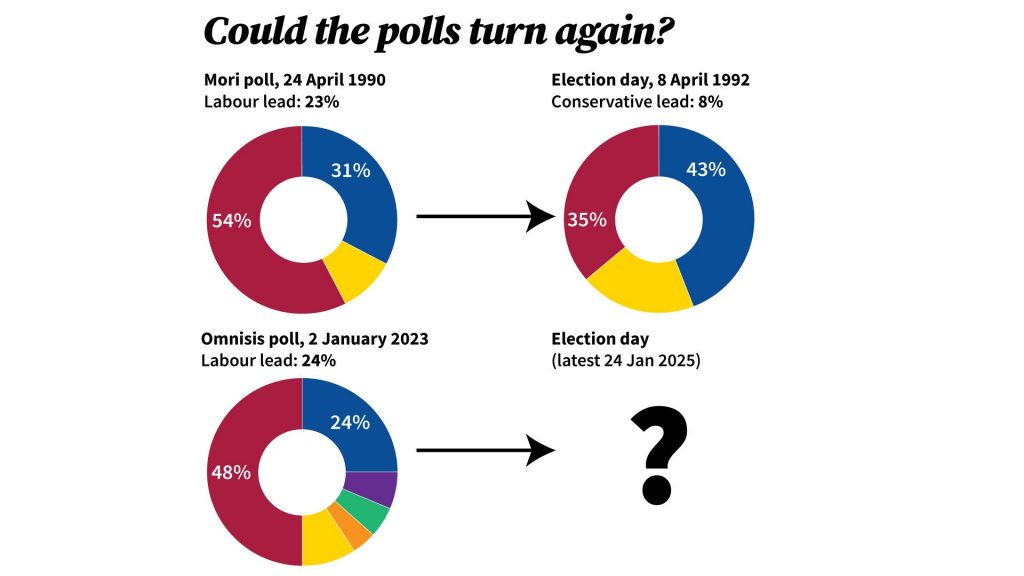

Popular history recalls that opinion polls were sure of a Labour victory in 1992. The reality is quite different – while Ipsos Mori, for example, showed Labour a maximum of 15 points ahead of the Tories in Thatcher’s final days, for most of 1992, Labour’s lead over the Conservatives was well within the margin of error. Pollsters were calling which party would sneak a narrow win, and called that wrongly.

All of that, though, is mere prelude to what happened next: within six months of his shock election victory, John Major’s polling sunk below that even of Thatcher at its nadir. Neither he nor his party recovered that decade. Major oversaw Black Wednesday – a particular embarrassment for a former chancellor – and the disintegration of his party over the EU.

Major’s already narrow lead quickly disintegrated. He was left paralysed in parliament, complaining of “the bastards” on his backbenches. He survived a doomed leadership challenge and limped on to the 1997 election. It is a testament to Major’s skill as a politician that he served a full five-year parliamentary term with his own mandate. It is a sign of how awful those five years were that they were capped by an unprecedented Labour landslide in 1997.

This is the “good” scenario that the Conservatives are pointing towards – they might be able to get the win that lets them limp on for another few years, destroying their party all the while. But however bad the bastards were in the 1990s, they are now on another level. The Conservative party is not so much already limping as dragging its dying political body by the elbows.

Rishi Sunak is already more unpopular than any party leader in history after 100 days – his predecessor, of course, saw her ratings drop even faster, but she did not make it to 100 days. Any residual benefits of the Treasury’s largesse during Covid-19 have evaporated. Where Major managed to lift his party towards his personal ratings, Sunak has simply seen his own plummet down to that of the Tories.

It gets worse for him. The Russia/Ukraine conflict is a far more dangerous and extended one than Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait ever was – and while supporting Ukraine’s valiant resistance against their invader with weapons deliveries and aid is a popular position, it is Boris Johnson who is most associated with that support. There is no political win for Sunak here, but clear political risk if the conflict goes south, or if he tries to deviate from Johnson’s position of all out support.

Sunak might console himself that the 2020s version of Black Wednesday has already taken place, thanks to Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng’s catastrophic emergency budget. But hoping to get the credit for clearing up the wreckage from that economic and political suicide bomb is to play 5D chess.

Reversing Thatcher’s biggest mistake involved a relatively popular set of shifts for Major – he could repeal the hated poll tax. Most people paid less (some considerably less) under the council tax system that replaced it, and relatively few noticed the hit from the increase in VAT that paid for it.

Sunak has no such luck. Truss announced a package of tax cuts for core Conservative voters, some of which she reversed and the remainder of which were reversed by his chancellor, Jeremy Hunt. There is no accompanying tax cut or boost to services that he can hand out, thanks to the economic damage those caused. As a result, Sunak has come in and actually increased taxes on his core base – while overseeing a public service crisis caused by the austerity cuts he now says must continue.

There is no expectation of decent economic growth to bail out Sunak’s dismal political accounting. Aside from his basic “competence” promises on inflation and growth – of which the less said the better – Sunak has pledged his short pre-election premiership on stopping small boats.

This draws attention to an issue that appals political liberals and moderates (some of whom normally vote Conservative), while also drawing the attention of hardcore conservatives to his party’s absolute failure to stop the travel of desperate people looking for safety by making threats.

Wherever Sunak might look to for relief, there is instead another dead end, or worse another fundamental crisis for his premiership. Where he does have a strong parallel with Major, it is where he’d least want it – Major’s premiership was mired by endless allegations of sleaze, and so too is Sunak’s. Any hope of starting a clean-break new era were swiftly dashed, not least by Sunak’s decision to reappoint several of the most contentious players to his first cabinet.

Where Major himself was largely seen to be above the various scandals – despite it later emerging he was having an affair with Edwina Currie – Sunak doesn’t have that same advantage. He faces questions on his tax affairs, thanks to his vast wealth and his wife’s non-dom status. People notice his willingness to take private jets and helicopters on the public purse. He struggles to be a relatable figure, unlike Brixton boy John Major.

Major managed to turn a good first 18 months into a relentlessly miserable further five years. Sunak is clearly trying to do the same, without noticing that his first 18 months is worse than the 1990s Tory party at its best. Given the Conservative party struggles to break above 20% in the polls, and sits 20+ points behind Labour in most polls, Sunak will almost certainly not get his next five years.

The real question is why would he possibly want them – even with a majority of 70, Sunak cannot pass anything even slightly contentious. His hopes of a legacy that might pay out in the long run, such as boosting productivity by reforming planning, are dead on arrival with his reactionary backbenchers. His hopes of resolving the Northern Ireland border and trade situation will be similarly scuttled.

Sunak is the accidental prime minister, installed when the party wanted any warm body in the office – and had to stop it going to the members, at all costs. It is telling of just how grim his situation is that the premiership of John Major is all he can hope for – especially when it’s an impossible dream