A bright pink sign contrasts with the dull grey of north London in January. It sits outside a converted Grade II-listed Georgian house, home of the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, and announces the exhibition Breaking Lines: Futurism and the Origins of Experimental Poetry.

On their honeymoon in 1947, the American collector Eric Estorick and his wife, Salome, visited the modernist Mario Sironi in Milan and bought hundreds of his drawings and pictures. Their collection is housed in the UK’s only gallery devoted to modern Italian art.

Although better known today for its contribution to the visual arts, futurism was founded and led by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Marinetti demanded that futurists reject classical art, destroy museums and libraries, prohibit pasta and sing the love of danger. His Futurist Manifesto was inspired by the exhilaration of a car crash and contained the infamous lines, “We want to glorify war – the only cure for the world – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman”.

The works are displayed as pieces of visual art. There are no translations, but even so, the exhibits have their strange effect. Displayed side by side they seem like extraterrestrial instruction manuals on how to build an alien society.

Gallery No 2 sets out the influence of the futurists on Concrete Poetry in postwar Britain, in particular on Dom Sylvester Houédard. Concrete Poetry’s credo was that the form or structure of a poem could carry as much meaning as its words. Houédard was a military intelligence officer in the second world war before becoming a Benedictine monk, and his work employs typewritten characters in spiral or grid-like patterns. They are puzzles to solve, again visual, as much as written works, exploring themes of transcendence and contemplation.

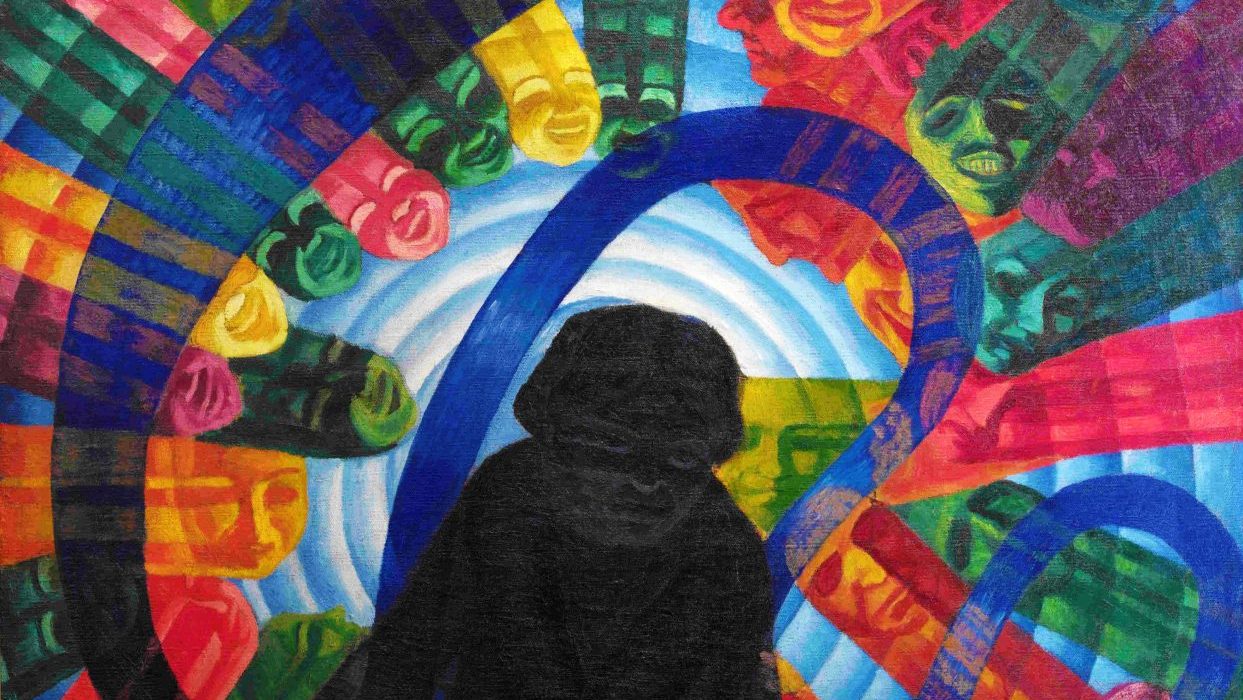

The upper galleries contain the permanent collection, including the work of futurist painters, such as Luigi Russlo’s Music, where sounds emanating from a silhouetted composer are “seen” in kaleidoscopic colour.

Marinetti saw fascism as offering the possibility of realising futurist dreams and in 1919 he co-authored the Fascist Manifesto. The exhibition says that he briefly recoiled from the movement. There was always going to be tension between the futurists and fascist conservatism, Roman Catholicism and emulation of the glories of Rome.

Marinetti is credited with defending artistic freedom against attempts to import Nazism’s campaign against “degenerate art”, but his overall attitude was of collaboration. After Mussolini was deposed, he supported the Nazi-established puppet regime. He died in 1944, his dreams unfulfilled.

Gallery No 5 contains paintings by Zoran Mušič, who was tortured by the Gestapo when they suspected that his artistic activities were a cover for espionage. He was sent to Dachau. His painting, Black Mountain, has an ominous, foreboding air. During the 1970s, he created a series called We Are Not the Last, after the landscape around Siena triggered memories of the piles of corpses from Dachau.

A conservatory extends the Italian cafe (pasta dishes available) into a tranquil garden. It provides a welcome contrast with the speed and violence of the futurist vision.

It’s ironic that the ones who wanted to destroy museums have themselves become museum pieces. Their euphoria over what the age of mechanisation could bring now feels naive and old-fashioned, analogue in our digital age. Yet their artistic influence survived the death of the ideologies they espoused.

The alignment of the futurists with fascism does have a modern parallel – across the Atlantic another unstable alliance has formed, of a retrograde politician, whose conservative supporters look back towards an unspecified time of greatness, and a forward-looking techno-utopian, united by a desire to sweep away existing norms. As this exhibition in a north London house shows us, such alliances don’t last.

Andy Owen is an author and former intelligence officer in the British Army