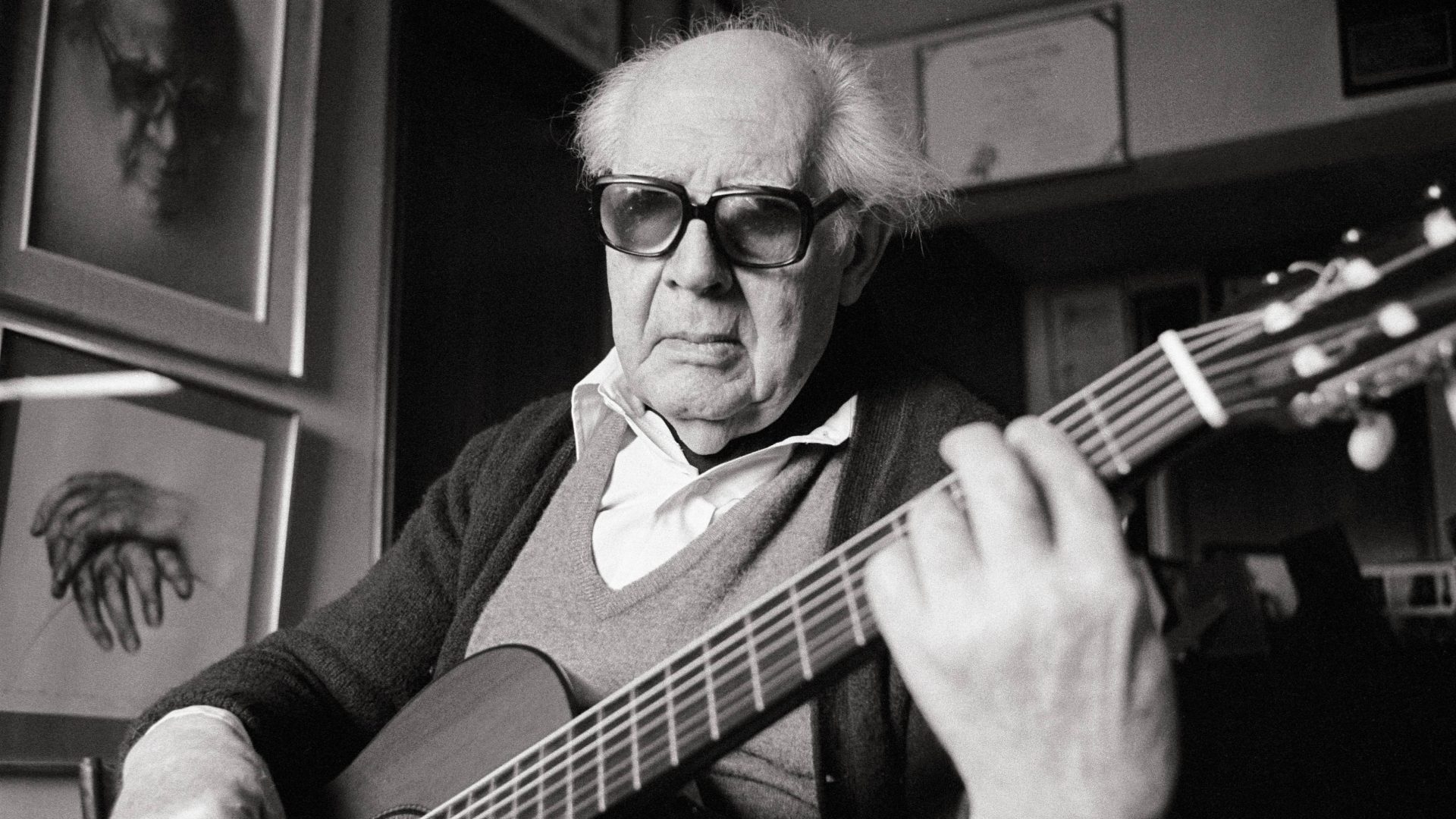

The extent to which Andrés Segovia revolutionised the global perception of the guitar is difficult to understand in today’s world where John Williams and Julian Bream are still household names and Xuefei Yang and Craig Ogden fill concert halls all over the world.

Yet not even a century has passed since Segovia first performed in London in 1926; concerts so revolutionary that astonished critics wrote as much about his choice of instrument as his virtuoso performances.

Before Segovia, the guitar was not an instrument to be taken seriously. It was sneered at, condemned to accompany cheap songs in cheap bars. Hence when Segovia arrived in Britain, despite a formidable reputation, he faced a dubious audience half-expecting to hear the musical equivalent of Mozart’s Requiem performed on a kazoo.

In a matter of minutes, everything changed.

The Yorkshire Post might have warned “music lovers” that “the Spanish guitar treated as a serious instrument will be a novelty”, but for the Evening Standard, “If anyone thought the guitar was a sort of old-fashioned ukulele, Señor Segovia soon undeceived them”.

The correspondent from the Chronicle had the most Damascene conversion. For them the guitar was “less a musical instrument, more a piece of stage furniture” to be lumped in with the banjo – “a useful twanging accompaniment on the sands at the seaside” – and the mandolin – “is and always has been an abomination” – yet they immediately found themselves utterly transported.

“Imagine the delight of all who heard Señor Andrés Segovia in finding that the guitar is one of the most intimate and delicate instruments,” they wrote, “one capable of the exquisite expression of the most subtle feelings.”

Segovia was first captivated by the guitar’s possibilities when, as a small boy, an itinerant flamenco player arrived at the family home near Granada to perform at the kitchen table in return for a few coins.

“At the first flourish more noise than music burst from the strings and, as if it had happened yesterday, I remember my fright at this explosion of sounds,” Segovia recalled. “I had sat down very close to him and now, rearing from the impact, I fell over backwards. However, when he scratched out some variations, I felt them inside of me as if they had penetrated through every pore of my body.”

The musician stayed for six weeks, commissioned to teach the six-year-old everything he knew before he took to the road again, never suspecting the contribution he had just made to the future of his instrument.

While he was instantly obsessed with the guitar, Segovia was never fully invested in the flamenco tradition. A recital at the villa of a local army officer would forge Segovia’s musical path when he heard a guitarist picking out a rare classical piece, at which “I felt like crying, laughing, even like kissing the hands of a man who could draw such beautiful sounds from the guitar! My passion for music seemed to explode into flames.”

Having acquired a guitar courtesy of a loan from a wealthy schoolfriend, Segovia set about adapting and learning Bach fugues composed for the keyboard and exploring the few works in the classical canon written for the guitar. By the age of 16 he was proficient enough to give his first public performance, earning an encouraging review in a local Granada newspaper.

“Reading it, I saw myself as world famous,” wrote Segovia in his memoir. “Suddenly I decided to be the Apostle of the guitar.”

To achieve that, however, he needed a repertoire.

While he would go on to give more than 5,000 concerts in 60 countries over more than 70 years, Segovia was initially frustrated by the lack of classical works written for his instrument. The Spanish composer Fernando Sor had produced a handful of pieces around the turn of the 18th century and Francisco Tárrega, a composer and guitarist in the 19th-century Romantic tradition, left behind a selection of pieces for the guitar, but there was barely enough to fill a single concert programme.

As his reputation grew, however, Segovia was able to inspire and even persuade some of the 20th century’s leading composers to write for the guitar, including Francis Poulenc, Paul Hindemith, Benjamin Britten and William Walton.

Not many musicians could exercise such a high level of influence, especially with an instrument deemed beneath the dignity of classical music, but as well as possessing astonishing talent and technique, Segovia was also blessed with unshakeable self-confidence to the point of arrogance. His line about being world famous and an Apostle for his instrument was not tongue-in-cheek or self-deprecatory – he meant it.

This single-mindedness, world-changing in terms of global perception of the guitar though it was, had its drawbacks. In 2012 Segovia’s former pupil John Williams criticised him as a musical snob who bullied his students.

So convinced was Segovia of his primacy in the guitar world that any student trying to develop their own brand of musical expression was soon brought sharply into line. In Williams’s recollection, what Segovia wanted was imitators, not ambassadors.

He left Spain at the outbreak of the civil war in 1936, settling for a few years in Uruguay because “the anarchists, the communists, the terrorists were tearing up everything” at home, but his willingness to return to Franco’s Spain to perform and eventually to live there again made Segovia unpopular with many of his peers.

His reasoning that “I need to touch the earth of my homeland periodically to receive new energy” didn’t wash with the cellist Pablo Casals, once a close friend who had arranged Segovia’s first recital outside Spain in Paris in 1924 and who refused to return home as long as Franco was in power. The pair would never reconcile.

Perhaps a rigid single-mindedness that could separate politics from music was necessary for the guitar to be established as a respected classical instrument. Certainly, whenever Segovia played, just him on stage, alone on a piano bench with a footrest and his guitar, nothing else seemed to matter.

He possessed something that transcended the carved wood and strings in his hands, the instrument that changed his life the moment a wandering flamenco player began to play in a kitchen at the dawn of a century, an instrument he mastered to the point where the New York Times would write of his first US performance in 1928: “He belongs to the very small group of musicians who by transcendental power of execution, by imagination and intuition create an art of their own that sometimes seems to transform the very nature of their medium.”