“I am telling you a drama, you cannot ask me bureaucratic questions. Which country? I don’t know. It is like asking me in which cemetery I wish to bury my children.”

On a humid Milan evening during the summer of 1984, an emotional Andrei Tarkovsky had just told a press conference he was seeking asylum in the west when a journalist asked where he planned to settle. The 52-year-old film-maker’s snapped answer revealed what an agonising decision he was making: his children were still in the Soviet Union and that night Tarkovsky was not sure he would ever see them again.

Flanked by previous defectors, the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, theatre director Yuri Lyubimov and novelist Vladimir Maximov, Tarkovsky revealed that his move had been prompted by the Soviet authorities’ refusal to grant him leave to remain longer in Italy after completing filming there on Nostalghia.

Over the previous quarter of a century Tarkovsky, one of the most gifted and innovative film-makers in the history of cinema, had been allowed to complete only six films. Given that these included such masterpieces as Andrei Rublev, Solaris and Mirror, his frustration was understandable.

“I am not a Soviet dissident,” he insisted. “But of the last 24 years I have been effectively unemployed for 18. There were times when I did not even have five kopeks for the bus.”

The rebuttal of his application was the final straw. It was not even as if he was dazzled by the prospect of life in the west; he was consistently appalled by the rapacious capitalism and consumerism he saw at every turn. This was a decision made in the name of artistic integrity, for which he was prepared to forsake everything he knew in the country he loved.

“One can only conclude that the destruction of culture is their plan,” he said. “That is terrifying, like committing suicide, because art is the soul of the people and people cannot live without their soul… This is why the lack of understanding from the Soviet authorities is not just insulting, it is destroying Russian culture.”

Tarkovsky was always a little too single-minded to stay on the right side of the regime. They wanted socialist-realist films of apple-cheeked workers pulling off five-year plans and historic epics where the people triumphed over malevolent aristocracy, not the profound, meditative autobiographical works of art in which he specialised.

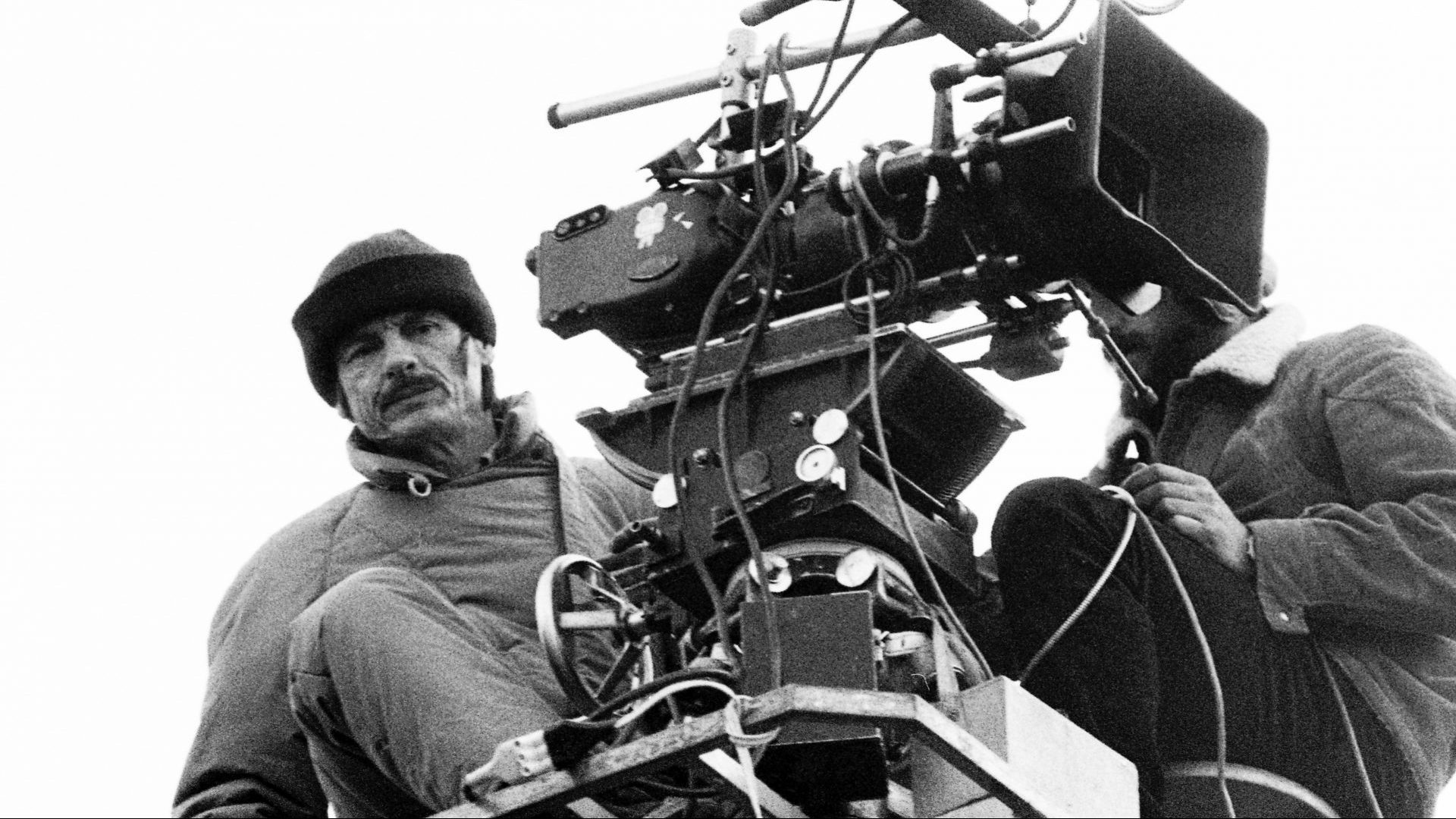

A Tarkovsky film was always, above all, a work of art: beautiful lingering shots that could remain on screen for minutes, inviting the viewer to contemplate and immerse themselves in the director’s world. As the New Yorker critic Alex Ross put it, “You could take 50 stills from any Tarkovsky film, mount them on gallery walls and make a stunning exhibition”.

He was always destined for the arts. His parents were poets and his early years were spent in an artists’ colony outside Moscow, a world of music lessons and art classes before, following the break up of his parents’ marriage, his mother moved the family to Moscow.

In 1953, the year Stalin died and Khrushchev began to introduce more liberal reforms, Tarkovsky applied successfully to the state film school, VGIK, where it was soon clear he was a visionary creative force. Indeed, his graduation film, The Steamroller and the Violin, won first prize at the New York Student Film Festival in 1961, and the following year his first full-length feature film, Ivan’s Childhood, won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

This success led to 1966’s Andrei Rublev, ostensibly a straightforward biopic of the 15th Century Russian painter of religious iconography but in Tarkovsky’s hands something much deeper and more personal that baffled state cinema authority Goskino. The film sat on their shelves for five years before receiving a very limited release, but a print made it to Cannes in 1969 where Tarkovsky claimed another prize.

This international success combined with the fact that Tarkovsky’s films were idiosyncratic rather than politically suspect left him not condemned outright, but certainly in artistic limbo. Science-fiction epic Solaris was released in 1972 and nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes, yet only shown sparingly in the USSR. Mirror followed in 1975, the autobiographical masterpiece of slow cinema that Goskino, the state committee for film production, dismissed as elitist.

When 1979’s Stalker received a strictly limited USSR release despite winning another prize at Cannes, Tarkovsky began to think seriously about his future. Filming Nostalghia in Italy confirmed that creatively there were huge advantages to being outside the Soviet Union, but his love of Russia bound him to home.

Tarkovsky suffered less than many of his contemporaries – the authorities recognised they had a genius on their hands, but knew his singular vision and stubbornness was never going to bend to their will – yet lived for film-making, lived for his art, and that was all that mattered.

“The artist is a phenomenon of nature, as unpredictable, as uncontrollable,” he said. “All the state wants is a stability that doesn’t exist in nature.”

Soon after his Milan announcement he travelled to Sweden to work on The Sacrifice, in which a man fearing his own death plans to escape his humdrum life by feigning insanity. While making the film the director was wracked with a terrible cough, one so bad that the producer, Anna-Lena Wibom, suspecting pneumonia, paid for him to see a specialist.

He returned saying they had ruled out pneumonia and given him something for his cough. When Wibom contacted the consultant, she learned that Tarkovsky had refused to submit to any tests and just asked for cough medicine. Marched back to the hospital, he soon learned of the advanced lung cancer that would kill him.

He died yearning for home at a time when Mikhail Gorbachev was introducing the perestroika reforms that may well have permitted a return. As it was, Gorbachev allowed Tarkovsky’s son to visit his dying father in Paris.

While his final years saw him riven by yearning for home and the family he had left behind, Tarkovsky found the bargain he’d made with himself still had him fighting a one-man war against creative compromise, the absence of state funding and the loss of his regular collaborators still in the USSR in particular. Yet he maintained to the end his conviction that struggle inspired great work.

“An artist never works under ideal conditions,” he said. “The artist exists because the world is not perfect. Art would be useless if the world were perfect as man wouldn’t look for harmony, he would simply live in it.

“Art is born out of an ill-designed world.”