It’s a normal working day in March 2022 at Berlin Hauptbahnhof. Thousands of commuters pass the bustling central train station, a symbol of hyper-modern 21st-century architecture in the heart of the German capital. The early spring sun shines brightly through the impressive glass façade. Just across the Spree River sits the German chancellery as well as the parliament at the Reichstag.

As I walk up the stairs to platform 13 to catch my train, the Eurocity Berlin-Warszawa arrives on the other side of the track. Hundreds of people disembark, mostly women and children: refugees from Ukraine. They are welcomed by volunteers in orange vests who direct them to the provisional welcome centre on the ground level. Since February 24, this train has been carrying people to safety from a war-torn country shelled by Russian bombardment, from cities like Kharkiv, Mariupol and Donetsk.

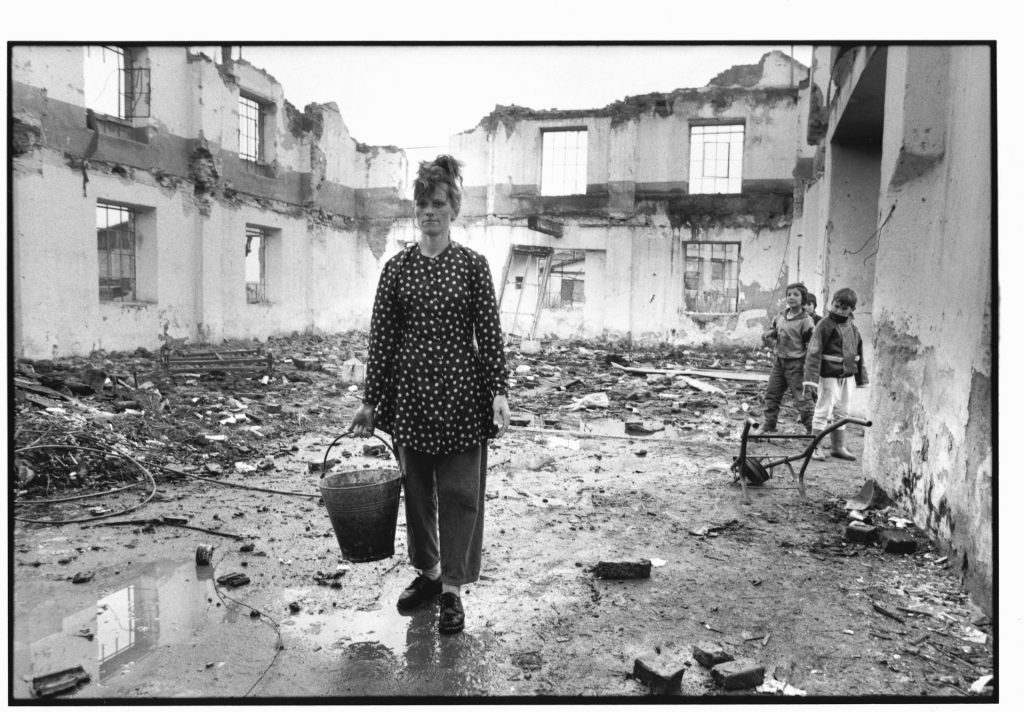

The scene seems almost surreal. The Ukrainian refugees do not look poor, they just seem exhausted and slightly disoriented. However, the most striking impression is the lack of luggage. An almost archaic moment that reveals the elementary question all refugees face. A rucksack, a small suitcase, children carrying their favourite teddy bears. That’s mostly it. The commuters’ faces passing by express a combination of curiosity and embarrassment, almost as if some odd voyeurism was drawing them into the drama of others.

Here, the story unfolds, the old saga of being uprooted: its latest chapter, Putin’s brutal war against the Ukrainian people, yet another story of mass displacement in the heart of Europe, unseen since the second world war. Stories of people who are forced to flee and live in exile are as old as the history of mankind. One of the Bible’s major narratives tells of deportation, exile and homesickness. Ever since, the story of displacement has continued.

The Late Middle Ages saw the expulsion of Spanish and Portuguese Moors and Jews following the so-called Reconquista. The expelled Iberian Jews took their heritage with them to various parts of the world, their Ladino language and culture survived in the old Sephardic centres in Salonica, Constantinople and Smyrna. From the 19th century, new concepts of nationhood and ethnicity paved the

way for a new scale of forced migration, as states tried to bring political boundaries into line with demographic ones. In this sense, the Balkan wars and the following first world war served as a rehearsal for the population “transfers” that would follow.

After 1918, democratic governments likewise sought ways to avoid conflict by reducing ethnic complexity. The “population exchange” between Greece and Turkey agreed upon in the Treaty of Lausanne was therefore praised as a symbol of unmixing ethnic groups, but it brought hardship and suffering to millions of Greeks and Turks alike. The Soviet Union perfected its method of “ethnic cleansing”. Stalin would simply deport entire groups – including Poles, Germans, Pontic Greeks, Tatars, Balts and Koreans – as a form of collective punishment.

Still, the Nazis’ war of conquest and extermination displaced people on an unprecedented scale. From the beginning of the war onward, massive expulsions became part of daily life in many parts of Europe. The number of people who were displaced, deported or turned into refugees during the second world war is estimated to be between 50 and 60 million – one-tenth of the European population. After the war, when the Allied powers redrew the map of central Europe with the Potsdam Agreement of summer 1945, millions lost their homeland, among them 14 million ethnic Germans and 1.6 million Poles.

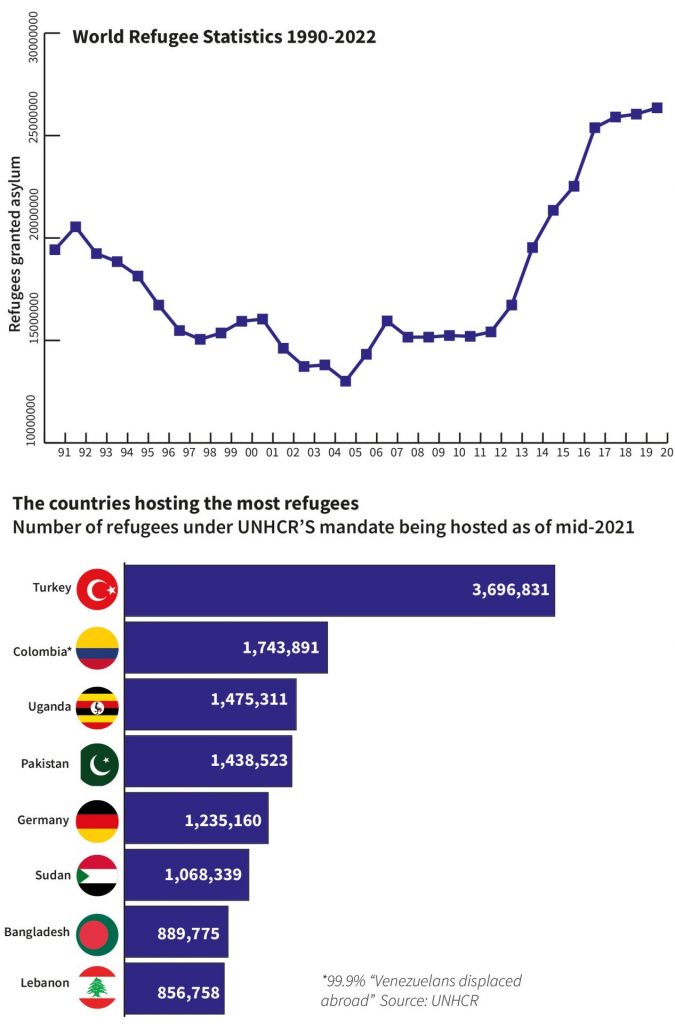

Ever since, displacement wrote dramatic chapters in contemporary history around the world. In 1947 “partition” uprooted 15 million people in India and Pakistan. Over the next decades, more stories unfolded with the exodus of Jews from the Arab world, the displacement of Palestinians, Koreans, Tibetans, Cubans, Vietnamese, Afghans and, most recently, Syrians and Darfuris as well as the Rohingya fleeing Myanmar into Bangladesh. War returned to Europe in the 1990s, causing incredible bloodshed in former Yugoslavia, which led to millions of refugees and ultimately to the genocide of Bosnian Muslims. The Caucasus region has been a constant hotspot for “ethnic cleansing” of Georgians, Armenians and Azeri. For 2021, the United Nations reported more than 83 million refugees globally. And in the last month alone, more than 12 million Ukrainians have been displaced.

The arrival of Ukrainian refugees at Berlin central station reminds me of a powerful image from my childhood. My favourite book was Judith Kerr’s autobiographical novel When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, in which the nine-year-old protagonist Anna must hastily leave Berlin with her mother and brother to escape the Nazis in February 1933. There is not much room in their luggage, so Anna must choose just one soft toy. With a heavy heart she decides against her beloved pink rabbit, leaving it behind.

In 2022, Ukrainian refugees are forced to make the same decisions as Anna in 1933. “When we leave somewhere, we take the time to say goodbye: to the people, the things, and the places that we’ve loved,” says the French writer Gaël Faye in his novel Petit Pays, based on his own childhood when he had to flee Burundi. Faye continues: “I didn’t leave my country, I fled it. The door was wide open behind me as I walked away, without turning back.” Refugees face similar challenges. Leaving home, most often for good, is a dramatic turning point in people’s lives and it is very often beyond our power of imagination to comprehend this loss.

Although the reasons and circumstances that drive people to flee can be very different, the concrete experiences of refugees, displaced people and exiles are similar. All must decide: What do I take with me? How much can I carry when on foot? Should I pack valuables, photos, jewellery and documents or better food for the days to come? Flight is a turning point, the termination of an unwritten agreement with one’s ancestors that has been valid for generations. Everything based on inheritance law suddenly no longer counts. Wills and investments in the future, land, savings accounts – at the moment of flight everything sinks into meaninglessness.

Outsiders can hardly perceive what it means to leave everything behind – except, of course, one’s life. Flight and fleeing are not an adventure. What was forgotten at home can never be retraced. In the moment, even refugees themselves are rarely aware that it is the way of no return. What does it mean for a farmer to leave his cattle behind? What does it mean for the elderly to bid farewell to their house, their neighbours and family for good? Refugees must not only abandon their material belongings, but their ancestors as well. Cemeteries are abandoned and graves grow over.

“The old Armenians of my childhood never had any graves at which they could weep for their parents. They carried their graves with them wherever they wandered,” writes Varujan Vosganian in his autobiographical novel The Book of Whispers, about the Armenian exile community in Romania, who survived flight, deportation and genocide. And finally, when children and grandchildren flee, what does it mean for parents or grandparents who are left behind – for good, and in many cases without any further contact – because they feel too old for an exhausting and troubling journey that only means uncertainty?

Uncertainty also accompanies refugees and displaced people on their journey. I am reminded of Anna Sudyn, who was driven out of southeast Poland in 1947 along with her Ukrainian family. She had survived Nazi terror, a concentration camp and forced labour. After she was freed, she returned to Poland. When, after all that, the Polish army set fire to her village, the family had to leave once again. This time they were to be deported to the areas previously inhabited by Germans.

They hurriedly packed a few belongings, including a stone, which Anna’s father believed was essential for their survival because stones were so scarce in their sandy homeland. Farming families had always used such stones to weigh down the cabbage barrel and so ensure the supply of sauerkraut and its essential vitamins for the winter. At last they reached Masuria, where they were to be settled. “When we arrived, dear God! So many stones! Whenever you bent down there was a stone.”

After arriving in their new life, refugees carry an infinitely heavy burden that includes an endless list of losses: intimate connections with family, friends and neighbours, familiar scents and sounds, food, dialect, language, landscapes – and above all an environment where they were able to read all the codes. An environment where they felt at home – where they simply belonged. Undoubtedly, there is a good chance of starting a new life, but coping with this total loss remains a life-changing challenge.

Thinking about what we would take with us if we only had five minutes challenges our perspective immensely. When we forget something at home, we go back. This certainty is excluded in the case of flight, where there is no going back. It is a forced departure into the unknown. Awaiting those who have fled on arrival, wherever it may be, are camps and transit centres, racism and hostility, and a future that may mean integration, assimilation or permanent exile. Ultimately, what unites them all is the memory of what they have lost, even across generations. Their loss of home is an existential experience, a radical break in their life story.

Uprooted refugees are confronted with sedentary societies that still hold the privilege of having a home. The latter are the ones who also decide the refugees’ fate. Refugees depend on their decisions, which determine whether they are welcomed, accepted or denied. Often, they are seen in apocalyptic terms and metaphors from nature are routinely applied to them: “flood”, “avalanche”, “wave”, “torrent”. Such phrases serve to awaken a sense of imminent natural catastrophe and encourage fears.

In 2015, Germany’s biggest tabloid ran the headline “Cologne is drowning in a flood of refugees”. And these metaphors depicting events in terms of powerful natural forces are inevitably followed by others calling for the erection of barriers, used by populists to build “dams” and other means to hold “them” back. The Brexit campaign by Nigel Farage and others used the same imagery, showing a crowd of non-white refugees as “intruders” using the disgusting headline “Breaking point”.

To this day, refugees continue to provoke; they are seen as disturbing nuisances, illegal invaders and a threat to local communities. The very nature of being forcibly displaced and arriving in a foreign and often hostile environment has been witnessed with many refugee groups in various parts of the world. The postwar German refugee experience can provide answers to universal patterns of refugee narratives. Up to 14 million Germans arrived in the allied-controlled zones of Germany after 1945. On top of this, to date, an additional estimated 4.3 million displaced ethnic Germans or those of German descent have “returned” to Germany from central and eastern Europe, especially from the former Soviet Union. In total, the figure is close to 20 million German refugees that needed to be absorbed. This means that today approximately every third living ethnic German is either a refugee or the descendant of one.

Their very existence symbolises the massive changes that German society faced after 1945, when millions of homeless refugees tried to find a new home. Narratives of displaced Germans often recall how it felt to be exposed to such verbal discrimination – being denounced as “Polacks” or “gypsies”. Sometimes hosts accommodated refugees only with the persuasion of a US or British soldier’s machine gun. This case goes to show that solidarity for refugees is hardly ever sustainable, especially if they stay too long. Even the so-called Willkommenskultur, witnessed by Syrians, Iraqis, Afghans and others in Germany in 2015, was short-lived.

Refugees are often confronted with hostile reactions that challenge their identity anew. Therefore being uprooted enhances the notion of “exile”. The writer Reinaldo Arenas experienced his exile in the US as a constant conflict between here and there. In an interview for The New Yorker in 1983, he was asked if New York was a good place for him to write. He answered that his exile from Cuba was only a physical one: “Every person who lives outside his context is always a bit of a ghost, because I am here, but at the same time I remember a person who walked those streets, who is there, and that same person is me. So sometimes I really don’t know if I am here or there.” For Arenas, the inner ambivalence caused by his uprootedness remains and he has no means to overcome it. Like him, many refugees live in permanent exile, unable to take root again in new places.

Those who could always be certain about their home never needed to ask questions about belonging, identity or roots – and those who lost their home were constantly forced to raise such questions. Jean Améry once said what is true for all refugees: home very often only gains importance after you have been uprooted. This is why refugees often idealise their lost homelands. For them, home becomes an ultimate projection. Initially refugees long to return, and after they realise this is no longer possible, it becomes an idealised space.

Moreover, the term “integration” needs to be critically questioned – starting with its very meaning. Integration is easily exhausted as a euphemism with its very materialistic meaning. It mostly means a job, shelter, a house. However, as was shown, the counter-narrative of individual stories often underlines disintegration or exile as refugees sacrifice a huge part of their existence.

They suffer a tremendous material and immaterial loss, including their culture and identity of origin. Again, after their arrival their rescued identities are challenged by foreign and often hostile societies. The latter can also obsess about marks of difference and argue that the incomers have failed to integrate. Refugees often continue to feel uprooted long after they have relocated. It can change over time, yes, and integration is possible, but there is no guarantee. They feel as if they have yet to arrive and do not belong, while the surrounding world easily mistakes their existence as perfect integration.

“Arrival” cannot be ordered by official statements or claims of successful integration. For most refugees, traumas, often due to experiences of violence and humiliation, are kept behind closed doors, privatised in the protected space of the family. Rupert Neudeck, the founder of the rescue campaign Cap Anamur saving Vietnamese boat people in the 1980s, was a German refugee himself and remembers his flight from Danzig at the end of the second world war.

“The old images lasted and shaped my future life – along with the important message: most people’s biographies are actually linked to migration or being refugees. Even those who are sure that their families are rooted where he or she now lives – but one should not be too sure or complacent. It could always happen that he or she or their descendants will be forced to leave. Because there is a refugee in all of us.”

Refugee stories provide a different view of the world and show the fragile nature of our existence. Listening to individuals is a key tool for empathy. It also helps to overcome the anonymous numbers that populism uses to attack refugees. It is long overdue that refugees should be subjects of history who change and shape societies instead of merely helpless victims.

Their voices should be heard in order to enable sustainable support and solidarity. Finally, refugees should never be simply accepted as “collateral damage” to conflict and war. Because they remind us all that at some point it could be us.

Andreas Kossert is a historian