When André the Giant was a boy during the 1950s, an Irishman bought some land close to his family home at Molien, near Grenoble, and built a house there. André, already six feet three inches tall by the age of 12, would walk the two miles to school every morning as part of a group of local children, their route taking them past the new dwelling.

On some mornings the Irishman would drive into town in his flatbed truck and stop to pick up the children, including young André Roussimoff, who would pile excitedly into the back of the truck then hop off at the school gates. Which is how André the Giant came to be chauffeured to school by Samuel Beckett.

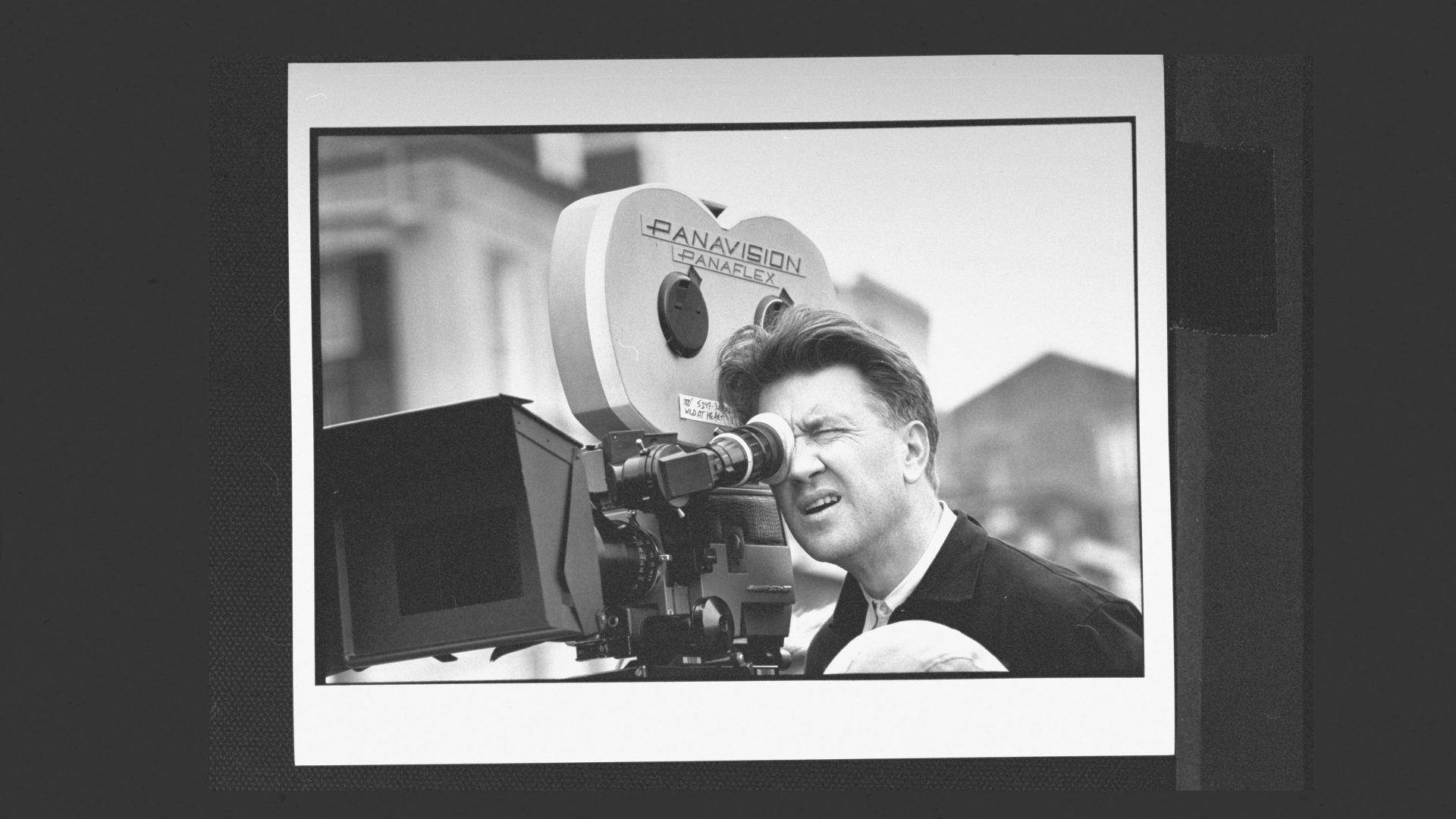

The life of André the Giant threw up many myths, some perpetuated by the man himself, but this one was true. Even so, Roussimoff embellished the tale. On the set of the 1987 film The Princess Bride, in which Roussimoff played the gentle giant Fezzik, he told co-star Cary Elwes that Beckett gave only him a lift because he was too big to fit on the school bus. It was an ideal arrangement, he said, because Beckett drove a convertible which meant André could ride in comfort. The pair, he said, became close.

“I asked André what he and the famous author talked about when they were together,” Elwes recalled. “Cricket, mostly, he said.”

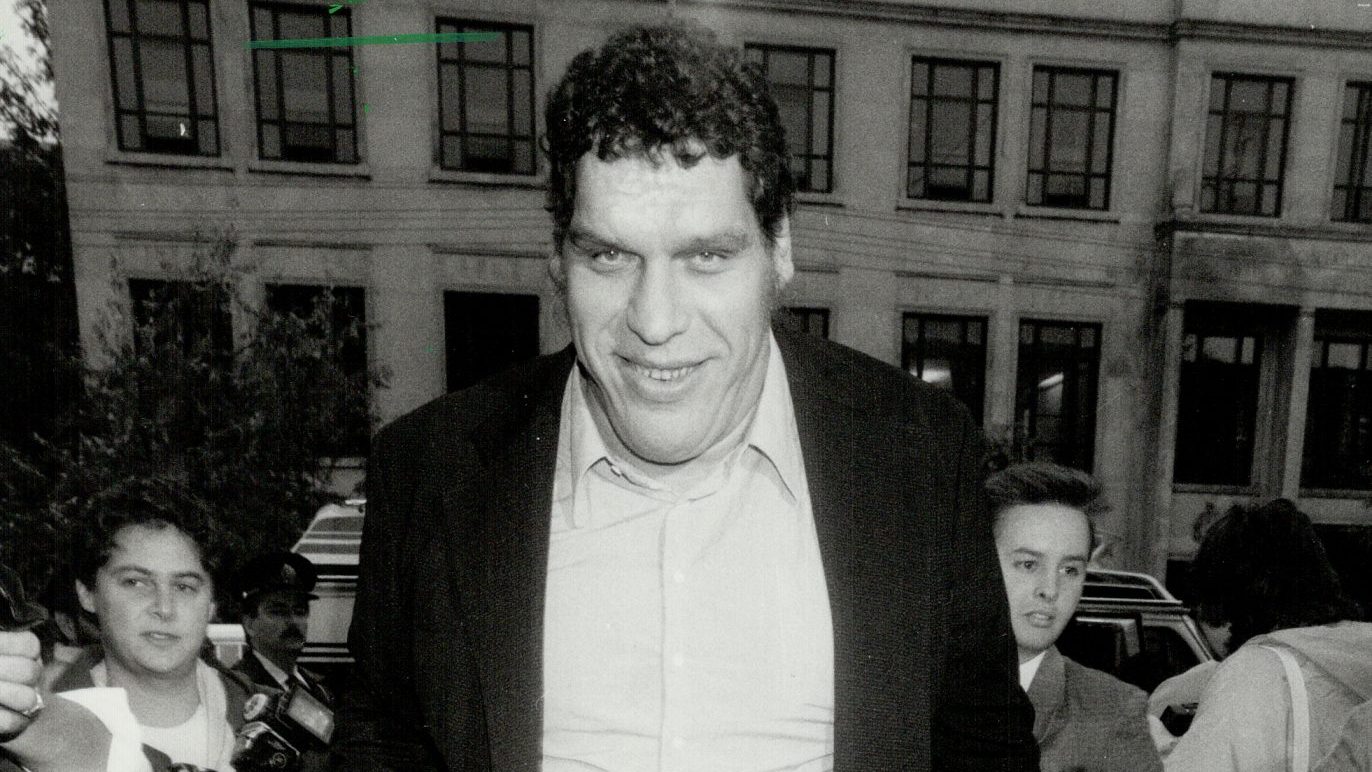

Little blame can be attached to Roussimoff for exaggerating the truth of his stories because everything about the wrestler and actor was already exaggerated. In his prime, he measured seven feet two inches, weighed well over 500lb (nearly 36 stone, or 228kg) and wore size 26 shoes.

He had to stoop to pass through every doorway he encountered and would dream wistfully of visiting the theatre, an experience closed to him because he was too big for the seats. His wrists measured a foot in circumference and he never fulfilled an ambition to learn the piano because his fingers were too big for the keys.

His immense size meant children were often afraid of him. “Sometimes when I go to the home of people with small children they will run from me even though they have seen me on television,” he said. “I understand. But it’s a sad feeling for me.”

He stood out everywhere he went, even in death. He died of heart failure in a Paris hotel having travelled from his home in the US for his father’s funeral. His will stipulated that he should be cremated within 48 hours of his death and his ashes scattered on his 200-acre ranch in North Carolina, where he raised Texas Longhorn cattle. Not a crematorium could be found in Paris with a furnace large enough, however, so his body had to be collected and flown home for cremation a few days later.

André the Giant was never destined to make old bones. He suffered from acromegaly, an excessive secretion of growth hormones that can produce results similar to gigantism. While the condition gave him a distinct advantage in the wrestling ring, it came with considerable downsides.

Acromegaly put incredible strain on Roussimoff’s physique and by 1986 he walked with a stoop so severe it required major spinal surgery, for which large surgical instruments were specially commissioned. After that came operations on both knees to help prevent a man barely into his 40s from moving like someone twice his age.

Roussimoff had always known he would be lucky to see 50, developing an innate fatalism that combined with a desire to wring as much as possible from his shortened life to fuel a copious appetite for alcohol.

The stories were legendary: how he drank 72 double vodkas in one session, the time he passed out in a hotel lobby after 120 beers and they had to put a grand piano cover over him to pass him off as a piece of furniture until he woke up, how the NYPD once had an undercover officer tail him on a drinking session in case he fell and crushed someone, how he would regularly consume 7,000 calories a day in alcohol alone.

“It was on his mind the whole time that he was destined to die young,” said his friend and manager Frank Valois. It made him lonely, a perpetual outsider, but André the Giant would make the most of his 46 years.

His wider celebrity has obscured just how significant a wrestler he was. From the early 1970s until the rise of Hulk Hogan, André the Giant was the most famous wrestler in the world, at his peak earning more than $400,000 a year.

He dominated the WWF for more than a decade until Wrestlemania III in 1987 when he was defeated by Hogan in front of 93,000 people at the Pontiac Silverdome, the bout finishing with Hulk bodyslamming his massive opponent. By then Roussimoff was in constant pain and had barely six years to live.

“Even though André was hurting really bad he wanted my career to go up a level,” said Hogan at Roussimoff’s funeral. “I bodyslammed André the Giant at the Silverdome only because he let me, telling me ‘slam me, boss’. I’ll never forget his generosity.”

Roussimoff was the first wrestler to make the transition from ring to screen, appearing on shows such as The Six Million Dollar Man and most famously Fezzik in The Princess Bride to become a celebrity way beyond his sport.

“He loved that movie,” said his long-time assistant Frenchy Bernard. “We’d watch it every three days. Everyone had to sit down and watch it. You didn’t say no.”

Grenoble-born to a Bulgarian father and Polish mother, Roussimoff first showed an interest in wrestling at the age of 16, being taken under the wing of Valois and billed variously as The French Giant, Monster Eiffel Tower and André the Butcher.

After early success in France he crossed the Atlantic to establish himself in Canada, becoming impossible to beat until in 1973 he attracted the attention of WWF promoter Vince McMahon Sr. McMahon added him to the bill at Madison Square Garden, dubbed him André the Giant, and launched a 20-year career that saw Roussimoff become the first inductee into the WWF Hall of Fame.

Yet behind it all was that shadow of impending doom, not to mention the paradox of being a perpetual outsider who was always the centre of attention.

“Everything about him, the way he was put together, was the living embodiment of our childhood dreams of giants,” said former opponent Terry Todd. “He bore more than his fair share of the burden.”