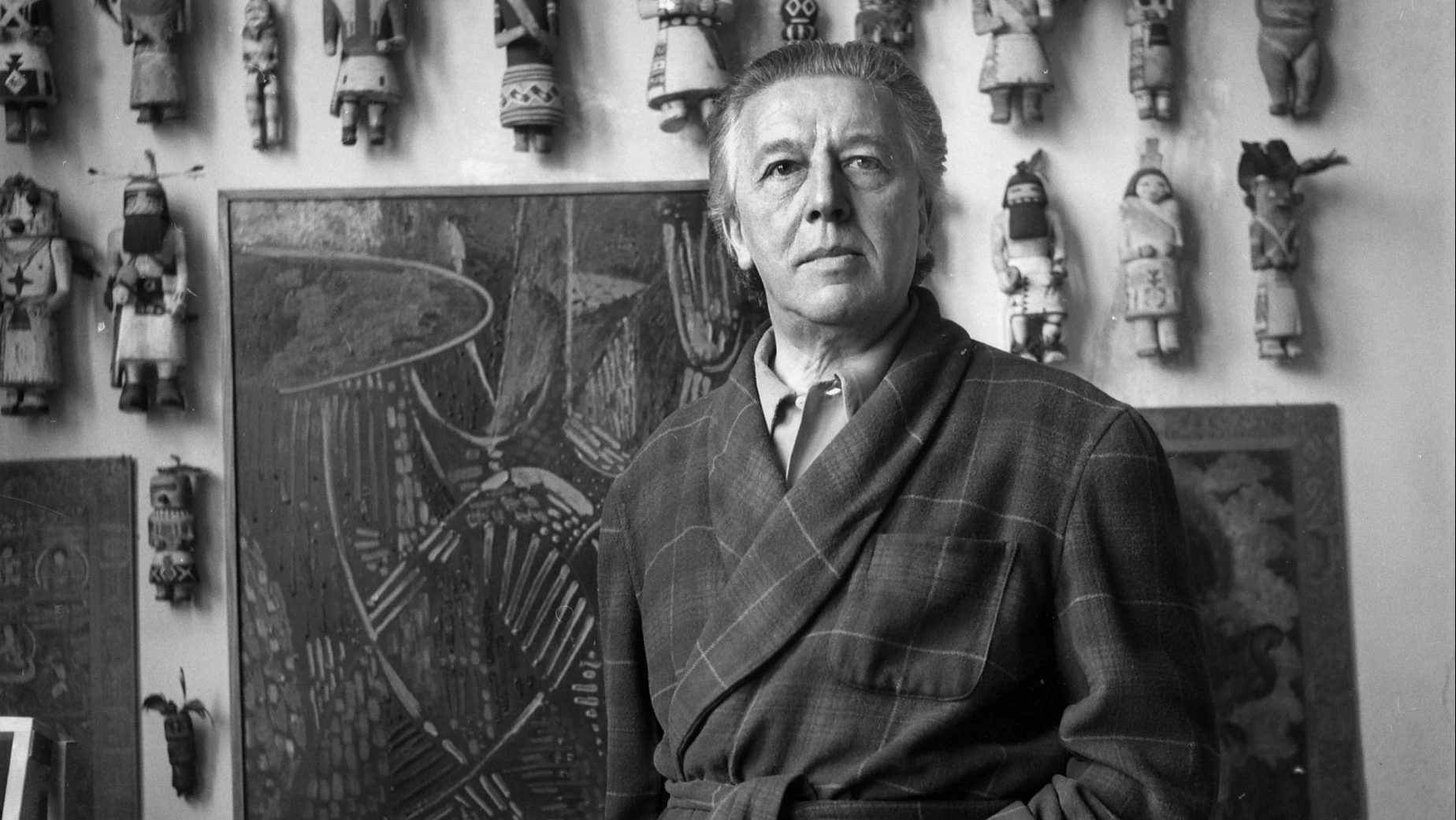

The word “surreal” has been diluted over the years to become in effect a pseudonym for “unusual”. A century ago, however, it was a genuinely revolutionary word founded in literature and poetry before becoming almost exclusively a movement based in art and sculpture. Unusually for a global cultural movement with a lasting and evolving legacy, this one can be traced back to one person – André Breton.

Designed to unhitch the consciousness from established routines and influences and reveal the unfiltered raw material of the mind, surrealism explored creative paths that led its proponents in new directions while making iconoclastic attacks on everything from science to the Catholic Church to established cultural figures of the time. This combative stance even led in the years leading up to the second world war to the surrealists becoming fellow travellers with movements of political reform, most notably communism, a connection made almost unilaterally by Breton.

Hence an occasion in Mexico in 1938 that justifies use of the word surreal even though it was unrelated to art, sculpture, literature or poetry.

One evening that summer Breton found himself in a flea-ridden cinema in a small Mexican town seated next to the exiled Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky watching a low-budget American western dubbed badly into Spanish, throughout which Trotsky whispered opinions about the predictable nature of the plot and giggled at the hamminess of the acting.

Trotsky was one of the few people for whom Breton felt something approaching awe. When he read Trotsky’s biography of Lenin, Breton fell head over heels for dialectical materialism and went in search of its leading proponent. The men spent four months together that summer, finding each other by turns fascinating and frustrating and eventually announcing the foundation of the International Federation of Independent Revolutionary Art.

The collaboration between surrealism and communism soon foundered, however, partly when news of the Stalinist show trials emerged, to Breton’s dismay, but mainly because the revolutionaries struggled to appreciate any link between the indulgence of avant-garde artistic pursuit and the proletarian struggle.

“Perhaps I am not very talented as an organiser,” wrote Breton to Trotsky in 1939 of their failed escapade, “but at the same time it seems to me that I have run up against enormous obstacles.”

Underpinning this statement was the deep self-belief that drove Breton, making him a far-seeing genius for some but an ego-driven autocrat for others. Unshakably intense and dismissive of those who failed to meet his singular expectations, Breton would defend his positions to the point where long friendships were destroyed, while also earning the support of aspiring artists and writers.

For Salvador Dalí, in the surrealist movement “there was a censorship determined by reason, aesthetics, morality, of Breton’s taste”. The critic Alain Bosquet noted in Breton the clash between “the proverbial purity of his intentions and the tranquil rage which left nothing intact from the moment he decided to love or abhor”.

Breton would even put Dalí on trial in 1934 accused of betraying surrealism by producing work that was contrived and commercial, expelling him from the movement with an emphatic guilty verdict (Dalí arrived at the surrealist court swathed in layer upon layer of clothing, which he removed piece by piece whenever Breton spoke).

For all his unorthodox methods and opinions, Breton never lost a desire to create and foster an entirely new mentality, one free of the accepted orthodoxies of reason and habit. He sought to bring together the dream-state from which we wake every morning and our actual perceptions, a mingling of inner and outer reality that would forge a new creative path.

In 1924 Breton published the Surrealist Manifesto, a document that defined surrealism as “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought”.

His goal was the emancipation of humanity from the binds of the ego and of life from the chains of reality. “Reality,” he wrote, “is a miserable mental expedient.”

The roots of Breton’s idealism lay in his experiences during the first world war. A young medic from rural Normandy, the son of a policeman and a seamstress, Breton was fascinated by Freud’s revolutionary theories in psychoanalysis; techniques he used working with traumatised soldiers in psychiatric hospitals.

The strange utterances he heard from men exposed to the nightmarish circumstances of the front fascinated Breton, particularly in how they appeared to come from beyond a conscious mind shut down by trauma.

At the same time he discovered the hallucinatory verse of Arthur Rimbaud, and when in 1918 he read the symbolist poet Pierre Reverdy’s theory that “the image is a pure creation of the mind that cannot be born from a comparison but from a juxtaposition of two more or less distant realities” it confirmed to Breton that surrealism was the way forward.

His first tangible surrealist experience soon followed when, just as he was about to fall asleep one night, the phrase “there is a man cut in two by the window” came into his mind. Invigorated by what he considered to be a voice from somewhere beyond his conscious mind, the words fired the foundation of one of the most significant artistic and cultural movements of the modern age. Here, Breton felt, was something that went way beyond the mere random expression he saw in Dadaism. Here was a discovery that went beyond art and culture capable of changing the world.

The horrors of war had spawned a new, widely held, forward-thinking optimism that humanity might realise it was better than that. For Breton, the potential for a new age of global harmony would be found in the power of subconscious creativity, ideas that may have failed to win over the communists but found loyal sympathisers across the world.

In June 1936 he opened the first International Surrealist Exhibition in London, where he was described by the Daily News as “the Surrealist leader since the movement started, enormous head, thick curly hair above a sage green suit. He speaks in passionate French, urging us to make our dreams, our desire, master of the world – to change life.”

There was, the newspaper reported, “loud applause at this idea”.

“All my life, my heart has yearned for a thing I cannot name,” he wrote in the Surrealist Manifesto. In that applause he heard confirmation he had truly found his life’s purpose.