For many people, it’s the voice. For others, it’s a cheesy song, a windswept beach and a cigarette.

Jean-Louis Trintignant, who died last week in the south of France aged

91, spanned so many decades of French and European cinema that he

had come to mean something highly personal to every generation.

He was the hapless lover of Brigitte Bardot in Roger Vadim’s And God Created Woman and although both stars were making their screen debuts in that 1956

landmark, it’s mainly remembered as Bardot’s bombshell breakthrough. There’s a hilarious and quite famous still image of Trintignant buried in Bardot’s cleavage, a quintessential cliche of the French sex comedy. In real life, he briefly became Bardot’s lover, even while she was with Vadim.

He played the comedy very well, although that was never destined to be

Trintignant’s forté. He didn’t like mugging for the camera or even being

a movie star. “To be a blank page, to start from nothing, from silence,” he

would state as his goal. “From then on, you don’t need to make a lot of noise to be heard.”

Countless times throughout his career he would withdraw into a semi-retirement and a silence, practically a recluse, tending to his vines on his

estate at Uzes, where he’d produce a silky Côtes-du-Rhone named Rouge

Garance, after Arletty’s character in Les Enfants du Paradis, another of France’s most distinctive voices. Famously, any director who wanted

Trintignant would have to travel to Uzes and coax him out of his olive groves back on to the screen.

Shyness always haunted him. He originally wanted to be a film director but kept getting cast in theatre in Paris in the 1950s, finding he was able to hide behind his characters. He worked with Eugène Ionesco and was part of the Left Bank scene and the Théâtre National Populaire.

The fledgling career was interrupted by military service, hellish for a man

who had hit the headlines for being Bardot’s lover. Bullied by officers in

the Algerian war and hospitalised, he returned to poor reviews on stage as

Hamlet.

Vadim, of all people, offered him a lifeline with a part in his modern-day

1959 jazz update of Les Liaisons Dangereuses, as Danceny opposite Jeanne Moreau and Gérard Philipe and he began to find his way in the New Wave, growing into his face until he hit the big time as a racing driver in Un Homme et Une Femme (A Man and a Woman) by Claude Lelouch, which somehow won the Palme d’Or in 1966 and, with its almost-parodic style, came to define popular French chic on the international scene with its lilting Francis Lai theme tune (still the signature sound of French sexiness) and its insouciance around marital fidelity. Co-star Anouk Aimée and he would reprise these roles another two times over the years, each time marking a passing of time, a signal of our own mortality and the art form’s ongoing existential crisis.

Perhaps his greatest run of form was in the late 1960s, when he won Best Actor at Cannes in 1969 for Costa Gavras’s political thriller Z, in which he played the stern, investigating Greek judge hid behind dark glasses, a less obvious role he had chosen ahead of the more flashy journalist, which went to Jacques Perrin.

Then there was Eric Rohmer’s Ma Nuit Chez Maud, in which Trintignant was the Catholic man who, faithful to a promise he’s made to himself to marry a blonde he’d never actually met, would rather talk all night than make love to the eponymous divorcee played by Françoise Fabian. It remains a key text of the New Wave and through it, Trintignant became a poster-boy for existentialism in the movies.

It’s an image Bernardo Bertolucci played with to great effect in The Conformist in 1970, casting him as Marcello, a servant of Mussolini’s fascist secret police, sent to carry out an assassination in 1930s Paris under cover of his own honeymoon. What a gloriously tense, stylish and sexy film it is, with Trintignant at his most inscrutable and complex, looking like a classic screen star at certain moments, and just a naughty boy caught at play in others.

It’s a brilliant hat-trick of movies and established him as an actor who could bring disenchantment to the screen while keeping his characters charming. There was a sarcasm and irony in his delivery, a slight rasp, a vague ennui delivered as a sigh, with a bass, velvety rumble that still twinkled. It became the voice of France, familiar to millions from the best-selling LP record he made in 1972 narrating Antoine de St-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince, a disc that practically every household owned and treasured and wore out with play.

He turned down Last Tango in Paris and let Marlon Brando take the notoriety. He said no to Francis Ford Coppola for Apocalypse Now and to Steven Spielberg on Close Encounters of the Third Kind, a role that went to François Truffaut instead.

He was often compared to Paul Newman, with the long marriage and the racing cars. But it was Jack Nicholson he most resembled on screen in the 1970s and 80s; at Stanley Kubrick’s insistence he took his first-ever dubbing role doing Jack Torrance on the French release of The Shining. His “Coucou chérie” is just as imitated and known in France as the original’s “Here’s Johnny”.

His passion for racing cars, made famous in Un Homme et Une Femme, was indulged off-screen and, taking part in the Le Mans 24-hour race, he had a bad crash that led to several operations and a permanent limp thereafter, a physicality that he made much of on screen. “I limp differently every time,” he would remark. There are a couple of films with the director Francis Girod worth checking out, big in France but less-known internationally, La Banquière (The Lady Banker) and Le Bon Plaisir (1984) in which he is quite terrifying, even horrible. In the latter film, playing a lame-duck president, he controversially admitted he was inspired by Mitterrand.

There are many others to revisit. Un Flic Story (1975); Rendez-vous, from 1985, in which Juliette Binoche made her breakthrough; The Last Train (1973) with Romy Schneider; Melancholy Baby with Jane Birkin and Merci La Vie for Bertrand Blier in 1991.

Personal tragedy weighed heavy on him. He lost his infant daughter Pauline while shooting The Conformist, a death that left him and his director wife Nadine in a state of mourning for ever after. Something was broken, they would say, and they shocked the world when they admitted that only the existence of another daughter, Marie, prevented them both from committing suicide in grief.

This weariness and mortality fed into his later roles and into his reluctance to haul himself before the camera. But each time he did so, the effects were stunning. In Jacques Audiard’s Regarde Les Hommes Tomber in 1994, the director described him as being like a “cornered animal”. He was wonderful for the same director again in A Self Made Hero in 1996, tapping into great wells of regret and sadness from his own war-ravaged childhood.

“I feel more comfortable when death prowls in my characters,” he said. “Even if nobody asks me, these are the roles that interest me.”

It’s visible in his troubling performance in Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colours: Red opposite Irène Jacob and in the twin role he took in one of the great ensemble pieces of the 90s, Patrice Chéreau’s 1998 funereal family comedy, Ceux Qui M’Aiment Prendront le Train (Those Who Love Me Can Take The Train).

The mortal blow came publicly, with the death of his beloved daughter Marie in 2003, bludgeoned by her rock star lover in a story that made headlines around the world. Father and daughter were often seen acting together, on stage in Paris and Avignon and it was to the stage that he became dedicated in later years after her death.

His poetry readings became the stuff of legend, definitive renditions of

some of France’s most famous words: Apollinaire, Boris Vian (with whom he

acted in Les Liaisons Dangereuses), Jacques Prévert, Robert Desnos. Being on stage with the poetry, the performance, the beauty of the sentiment, he said, saved his life.

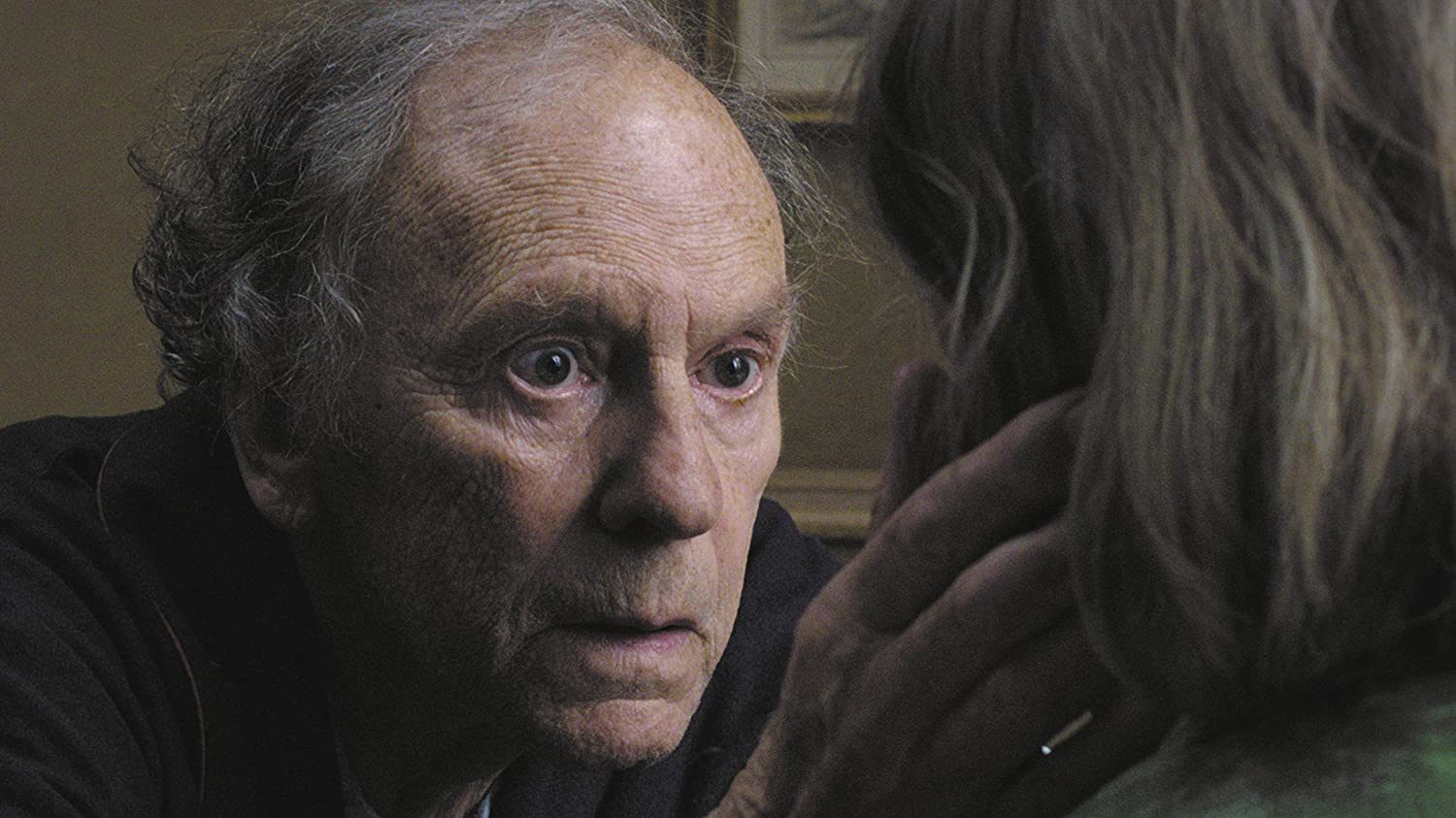

The on-screen comeback came after nearly a decade away and it could be his best performance, certainly his most garlanded, in Michael Haneke’s extraordinary 2012 Palme d’Or winner, Amour.

Playing opposite Emmanuelle Riva, Trintignant’s retired music teacher shuffles around his apartment caring for his wife, who has suffered a stroke,

a performance that aches with pain and love, that carries the weight of tenderness and responsibility, the burden of a new century.

Despite the great distress his character is in, the layers of guilt and ethical grief he wraps himself in before our eyes, there remains a soft-shoe lightness in his being. Is there anything, in the last 20 years of cinema, more touching yet more threatening than the scene with Trintignant facing the pigeon trapped and fluttering on his apartment floor?

Amour is a masterpiece, with two glorious performances at its barely beating heart, a piercing reflection on love and the power of memory. The disappearance of actors such as Alain Delon and Jean-Paul Belmondo in recent months has hit France hard, but none more so, it seems right now,

than Trintignant.

Knowing he was ill with cancer, Trintignant returned for Haneke in the

markedly inferior film Happy End in 2017. Something about the Austrian auteur’s precise and icy gaze must have chimed.

It’s a film in which his character nevertheless dominates superbly, an irascible haute-bourgeois patriarch who goes to his own death, in a

wheelchair, in the rising seas on the beaches of northern France – practically the same sands on which, in Un Homme et Une Femme 60 years

previously, he had first cemented his own iconic film reputation as well as

that of the country whose cinema he came to represent for so many audiences around the world.

After more than 120 films over 65 years, the legacy, the films, the voice

of Jean-Louis Trintignant will never be washed away.